The fire service that I have experienced for the last quarter of a century has remained an insular vocation, not taking full advantage of opportunities that are available to prepare its members for a career that requires not only manipulative skills but educational ability, too. The need for additional fire instructor education has been the basis for two data inquiries that are related to my doctoral research. My initial data gathering determined that outside educational opportunities wouldn’t be necessarily unwelcome.

One questions is, “Why have we not begun bringing in additional help?” I believe that the answer to this question is largely financial. Most of the citizens in this country fund the fire service through taxes: Budgets are driven by tax dollars and not by income from services provided.

If the fire service is to provide additional educational training for its members, we also must ask, “What should we include as curriculum?” and “How do we fund it?” The proposal that I have relies on existing programming opportunities that are within the fire service and the educational field.

Depending on the state of residence, the only requirements that are needed to be a fire instructor are a high school education (or GED) and completion of a 40-hour instructor class. (States are allowed to determine additional requirements.)

I envision a collaboration between the fire service and academia that involves existing pathways for both fire instructors and, hopefully, educators. Those who are responsible for educating future firefighters eventually would have formal educational training and, possibly, a teaching certificate. Although I believe that a degree should be necessary, it seems that isn’t achievable because of participant buy-in or financial constraints.

As an example of my vision, I reference the South Carolina Career and Technical Education (CATE) program. Subject matter experts are brought into high schools to teach vocational programming as part of the regular diploma program. Instructors are required to complete a five-year program that leads to a certificate to teach their field in the South Carolina school system.

Although CATE isn’t a degree program, it’s a solid foundation that could be utilized for a degree at a later date. I believe that this program, if not already available in most states, could be implemented at little or no cost to emergency services personnel.

Although initial benefactors of the program would be fire instructors and the students who they teach, ultimately, the public would be the recipient of the largest benefit. By providing better education to future firefighters, we create a better emergency response force and provide a better, safer service to the people who we serve. The stakeholders are those who are within the fire service and those who are within academia. The fire service stakeholders would be larger in numbers, though the academic ones would be more involved in the program contents. Being able to work within these two drastically different groups is paramount to success.

Who to convince

The biggest hurdle with the fire service is convincing the chiefs. They have final say in how things are run and on which policies and plans should be adopted. The backing of chief officers can make or break acceptance of a plan no matter how much traction it has with the line personnel.

Second to the chief of department is the training division. The means for implementing any new plan generally evolves from training officers, so having their support is key. The training division has the capability to smoothly promote and implement changes—or to slow the pace to an ineffective crawl.

The biggest number of stakeholders would be the instructors. Because most instructors volunteer for the position, they have the option to decide that they no longer wish to teach. Instructors must be participants in the planning process, because they not only are the beneficiaries of the process but must put in the most effort to change.

The academic group consists of administrators and educators who mostly are associated with vocational education programming and curriculum. Although school superintendents control the purse strings and personnel, I believe that the limited cost wouldn’t preclude involvement.

Educational professional development and continuing educational providers (often contracted through the school systems) also would be stakeholders. These presenters would be interacting with and benefiting from the participation of nontraditional educators. I foresee this participation as being beneficial to the creation of programming for different groups.

Necessary resources

I believe that most of the resources that are needed for this project exist. The school system has the formatting to train and educate vocational instructors already. Although the curricula might not be 100 percent correct, professional development and continuing education programming might transfer over to the fire service.

Printing of materials (outlines, schedules, etc.) could be absorbed by the instructor’s home department or provided in a paperless format. Materials, such as books, might be purchased by the local training divisions and kept for reuse.

A partnership with local technical and community colleges might allow fire instructors to use their facilities (libraries, labs, etc.) and to work, potentially, toward a degree program, which would help with the overall education of the instructors.

I don’t believe that this project would take long to put into practice, given that the majority of the work on the academic side is complete. Outlining, scheduling, policies and procedural documents for the fire service only should take a few months to produce.

Time plays a role in the capability for an outcome to be measured. The timeline for the CATE program is five years; I wouldn’t expect measurable results for the fire service in fewer than 2–3 years (from implementation).

The fire service would need to be aware of the academic calendar. Ironing out details of a collaborative endeavor while school is in session might prove frustrating.

Markers for success

I originally believed that the fire service’s history of not allowing outsiders in would be an enormous barrier. As survey results suggest, this might not be the case. Other roadblocks might revolve around the notion that change isn’t necessary if what we have is working, convincing them that just because it works doesn’t mean that we can’t make it work better. I believe that the only way that this can be proven is through implementation and evaluation of the program. My intent is to work with a small department that’s willing to support this endeavor, giving me data to convince doubters that this can work.

Down the road, school systems might benefit from having qualified instructors for vocational programming. Convincing school personnel to support fire instructor education relies on their interest in providing help to educators from a separate industry. There might be an opportunity for the academic world to benefit by using this programming to further their knowledge about adult learning and vocational education, but this is conjecture, not certainty.

Ultimately, the desired goal of this project isn’t only to increase the effectiveness of fire instructor education but to increase the quality of firefighter. Measurable goals most likely would be qualitative, though some quantitative data might be available. To determine the success, two factors would need consideration.

The first measurable marker would be a subjective assessment of the newly trained firefighters who these instructors taught. Comparisons of skill level and information retention over time would be used as identifiers. Based on their assigned officer’s assessment (after they graduate and are put to work), comparisons between them and prior graduates would be made. One would theorize that the students who had instructors who were more versed in educational methodology and learning should retain more of the skills. One also would theorize that students would be far more adept at adapting to new and difficult situations as their ability to process and apply information would be better.

The fire service has developed formative and summative assessments for their classes. Graded assignments would be utilized as the second measurable marker for success. Tracking and comparing grades of students prior to and after the program, one could derive data that could speak to a teacher’s delivery of material. These data could have any number of variables, and they shouldn’t be the sole basis for determining positive effect of the program.

Qualitative information for judging effectiveness also might be gained through interviews and surveys of instructors and students. Measurable success also relies on the participating instructors to remain excited about the program and the positive effect that students believe that they are receiving.

Pilot program

The department I am considering for a pilot program would hold at least one recruit school per year. The intent is to run the first recruit school without instructors being through the program. This will give me a control group of instructors and, hopefully, a better result when they are interviewed about their experiences and confidence before and after the program. The first three years would utilize these instructors for setting my baseline of student understanding and achievement along with starting data collection through instructor surveys about their thoughts on the program as they progress through. Continued assessment and modification (as necessary) would continue for the duration of the program.

Assuming a positive result, the third year would see the program introduced to surrounding departments and regions. These additional sites would be selected to represent different department sizes, budgets and personnel types (volunteer or paid). Data from these sites would be incorporated, and adjustments would be made accordingly as information is collected.

For a long time, the fire service has been more reactionary than proactive. The endeavor that I propose pivots our position to be educationally proactive. The idea is that we start at the beginning of the learning process by creating instructors who can grow with the industry. The project would give them more information, and the process of training and certification would be measured in years, not weeks. This “slowing down” of the process will lead to a more holistic educational experience for the recruits. Ideally, this updated educational model will revitalize not only students to become better firefighters but the instructors to become better educators.

Lack of inclusion from other industries has stymied the fire service for so long, and this has the chance to change all that. If successful, not only will there be benefits to fire instructors and students, but the possibility to look for other potential collaborations also would open up.

About the Author

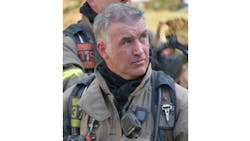

Chris Garniewicz

CHRIS GARNIEWICZ is a captain with the Bluffton Township, SC, Fire District (BTFD) currently assigned to Ladder 333. He has a master’s degree in education from Northeastern University and is an IFSAC-certified Fire Instructor 2. Garniewicz began his career in the Metro Boston area, serving as a volunteer firefighter and EMT.