It is interesting to reflect on the fact that some aspects of the fire and EMS world are constantly becoming more complicated. When I think back to 1971, when I started in our business as a recruit firefighter/EMT, fire station life was fairly simple. Much of the life-saving technology we take for granted today did not exist. But some things have not changed, and this column will explore one of the pillars of great customer service: simply, to “be nice.”

The history of “being nice” leads back to the writings and teachings of Alan Brunacini, the retired Phoenix, AZ, fire chief. Chief “Bruno” can go on for hours discussing the impacts and effects that simply being “nice” to our members and our customers can have on our departments and ourselves. No series of columns on personal rules of behavior and conduct would be complete without making mention of this “golden rule” – “be nice.”

As we have hit about the halfway point in this series, it is time for a quick review. I have received many nice comments about this series and like all Firehouse® Magazine contributing editors, I am delighted to hear from a most important group, our readers. A central theme from the comments is a request to put the rules into some sort of order; a hierarchy, as it were. But, by design, this series appears in no set order. Each rule stands on its own and is no more or less important than the other subject items.

The goal of every fire-rescue department should be to be a high-performance, high-trust agency known for its fairness, openness and transparency, and where good personnel morale is important to all. “Being nice” takes on a very significant role when it comes to reaching these benchmarks. The core value of “being nice” becomes the basis or foundation of reaching the lofty goal described above.

How “Nice” Begins

To put this concept into practice, think of the meanest kid in your neighborhood. Now, go on a virtual trip with me to the mean kid’s house and knock on his or her door. Who is most likely to open the door? My sense is that it will be a mean mom or dad or perhaps a mean older sibling. By now, you have caught onto the idea that mean people are living in that imaginary home. The point that I want to make is that the mean kid has to learn how to be mean from someone and that it is typically mom, dad, or older brothers and sisters.

The fire chief expects high-quality and trustworthy performance from all department members all of the time and under all conditions. Although a call may be the 10th or 15th response of the shift, it is the first one for the affected family. In most cases, it is the first and only time they have dialed 911 for our help. The chief needs (and perhaps should demand) the members to “be nice” to all of the customers all of the time. Therefore, the chief must be supportive of the members who answer the calls all hours of the day and night and under all conditions. Using the mean-kid theory, if the chief treats people in a mean way or if the organization is not supportive of the troops, it is a real stretch of the imagination to think that the firefighters will go out and be nice under those circumstances. Actually, the outfit is most likely to receive citizens’ complaints about poor performance and the negative attitude displayed by the workforce. Conversely, if the department supports and treats the workforce nicely, it’s more likely that the firefighters will meet or exceed the challenges that you put before them in the most professional way.

The next part of “being nice” is to remind your troops that they must “be nice” first. The organizational expectation is that our folks should “be nice” to other members and customers as the interactions are initiated, not waiting for the other party to “be nice” first. It is amazing how many negative issues can be avoided if the interaction starts off on a positive footing. We must remember that our customers are generally having a really bad day before dialing 911 and they typically have very little experience with emergency events. On the other hand, resolving emergencies and not adding stress to the customers’ day is our vocation or avocation when we pin on the badge.

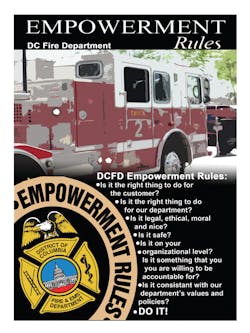

Empowerment Rules

The closing thought for this column is to prepare a set of empowering rules that can be published within your department. Members should feel empowered and supported to “be nice” to one another and to our customers. In organizations that are well supported, the list of “success stories” about conveying acts of kindness is just about endless with tales of matching departmental support from budget dollars to private donations to the old standby, a simple “Thank You!”

The District of Columbia Fire Department produces quarterly a “Great News” book that is a collection of dozens of thank-you notes and cards received during the previous 90 days. This publication is shipped to the mayor, city council and local media, giving these external stakeholders some idea of what is happening inside our organization. The “Great News” book is added to the department’s website so that our membership and others can quickly access this information.

Some departments have a customer service award process that recognizes members for going above and beyond to “be nice.” These types of programs should never interfere with the various types of recognition programs that are in place for fire, medical and rescue personnel; rather, “being nice” should be an embellishment of a departmental awards program.

The first part of “being nice” and high-quality customer service is being able to perform your job flawlessly. Nothing can replace being a high-performance emergency medical technician, paramedic and/or firefighter. Know your job inside and out and do it well, every time. “Being nice” will be a major added bonus for you, your department, and the citizens and visitors who call on you.

DENNIS L. RUBIN, a Firehouse® contributing editor, is a fire and EMS consultant. Previously, he was chief of the Washington, DC, and Atlanta, GA, fire and rescue departments. Rubin holds a bachelor of science degree in fire administration from the University of Maryland and an associate in applied science degree in fire science management from Northern Virginia Community College. Rubin is a graduate of the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officers (EFO) Program, is a Certified Emergency Manager (CEM) and has obtained the Chief Fire Officer (CFO) and Chief Medical Officer (CMO) designations from by the International Association of Fire Chiefs. He is an adjunct faculty member of the National Fire Academy since 1983. Rubin is the author of the book Rube’s Rules for Survival.

About the Author

Dennis Rubin

Dennis L. Rubin is the interim fire chief for the Kansas City, KS, Fire Department. Rubin was the fire chief of the District of Columbia Fire and Emergency Medical Services Department and the Atlanta Fire Rescue Department. He holds a master’s degree from Waldorf University, a bachelor’s degree from the University of Maryland and an associate degree from Northern Virginia Community College. Rubin is a 1993 graduate of the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program and obtained the Chief Fire Officer and Chief Emergency Medical Services Officer designations from the Center for Public Safety Excellence. He is an adjunct faculty member at the National Fire Academy and the author of several fire service textbooks.