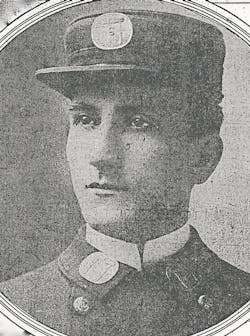

FDNY Battalion Chief John Howe: A Fireman's Fireman

The FDNY Department Order dated Dec. 23, 1913, announced the retirement of Battalion Chief John P. Howe at 8 A.M., Dec. 24, 1913. This was, and still is, common practice in the FDNY. All appointments, promotions, retirements, departmental charges and deaths are noted in the orders as a matter of record.

What was unusual about this announcement was that in addition to listing the customary name, date and pension amount, it went on for two paragraphs listing the heroic deeds Howe provided in his 25 years of service. It chronicled the 10 times his name was placed on the department’s Roll of Merit, an unprecedented accomplishment. But even at that, the list of rescues only scratched the surface of a brilliant career.

Just part of the job

Howe’s FDNY career began on Jan. 1, 1890, when he entered the East 28th Street quarters of Ladder Company 7 in Manhattan. A quick learner, he began his career with another young fireman, William Guerin. Together they would rise through the ranks and become chiefs.

Only two weeks into their careers, Ladder 7 was sent to a fire in an oleomargarine factory on East 49th Street. At the height of the blaze, Guerin became disoriented and then overcome in heavy smoke. Howe realized his friend was missing. After alerting his officers and other members of the company, he charged back into the blazing building to search for his missing brother. Forced to the floor by thick, hot smoke, Howe crawled deeper into the blazing factory. Barely able to breathe, he came upon the unconscious Guerin. Grabbing his unconscious friend, Howe dragged him back toward the entrance while calling for help as his head swam with dizziness from the smoke.

Members of Ladder 7 closed in around the men and pulled them to safety. Guerin lay unconscious on the sidewalk with Howe slumped next to him gulping for air. The members of Ladder 7 returned to their firefighting with a different sense of this “new guy.”

The following year, Howe proved himself again during a building fire on Coentis Slip in lower Manhattan. As Ladder 7 arrived, two women were trapped at a fourth-floor window and one of them was climbing out and threatening to jump. As the apparatus slowed, Howe leaped to the ground with a scaling ladder in hand, raced to the building and started up toward the women.

As he reached their window, the heat and smoke behind the women was becoming too much for them to bear. He quickly helped one woman out onto the scaling ladder and passed her to another fireman who had just raced up a portable ladder placed next to Howe. The second woman was quickly removed in the same way. These were the first of Howe’s many rescues. In the era of “iron men and wooden hydrants,” these rescues were not even submitted to headquarters for meritorious consideration. It was just part of the job.

14 saves in 15 minutes

The first time Howe’s name was placed on the Roll of Merit was for his actions at a Pearl Street tenement fire on Jan. 10, 1894. It was 4:30 in the morning when firemen pulled up to the old double tenement. Howe made trip after trip into the blazing building, returning each time with a person pulled from the furnace-like third floor. Howe single-handedly saved the lives of 14 people in 15 minutes. His actions on the upper floors of this building, particularly the rescue of two women, gained notoriety for the young fireman. Conditions became so severe that Howe was badly burned. On May 26, 1895, Mayor William Strong awarded the Pulitzer Medal to Howe in recognition of these rescues. In 1896, Howe was placed on the Roll of Merit on two occasions, for his actions on May 6 and Dec. 30.

Early in the morning of Saturday, Jan. 2, 1897, the bells in the firehouse tore the firemen from their beds and out the doors in a matter of seconds. Howe was driving Ladder 7, a team of three horses pulling the rig swiftly through the Manhattan streets. Behind him was Fireman James Pearl at the tiller wheel. As Ladder 7 turned the corner and thundered onto Lexington Avenue, Howe saw flames shooting up the entire rear of number 94. The bright-orange glow showed fire from the cellar to the roof. Three men were trapped at a second-floor window with heavy smoke and flashes of fire pulsing behind them.

Sizing-up the dangerous situation, Howe stomped the brakes, jumped from his seat and dashed to the adjoining building with Pearl close behind. Up the stairs to the front window they bounded. Howe battered out the window and sash, then stretched his body outside, stepping up onto the sill while grasping the lintel. Pearl, a strong stocky man over six feet tall, moved in behind Howe and grabbed his leg.

Glancing down, Howe saw an iron fence with sharp pickets directly below him. There was no room for error. The trapped men were still screaming for help only five feet away – a long five feet. Howe stretched farther, sliding his foot across the gap between the windows. Feeling the small foothold ,he was now completely out and saw the iron pickets directly below him.

The first trapped man, Max Henschel, reached out for help. Howe pulled Henschel up and pressed him into the bricks, protecting him with his body as smoke and jets of flame pumped from the window nearby. He inched the man across the building’s front and handed him to Pearl. Howe then went and reached for the second man, Augustus Whiting. He brought Whiting across in a similar manner and handed him off to Pearl. The big fireman jerked Whiting into the room and dropped him on the floor with one hand while maintaining his grip on Howe. “Now for the other, John,” Pearl said.

Howe paused – his skin was burned and his lungs stung from the hot smoke he had swallowed. With his head swimming, he took a deep breath. Before he could ready himself, the third man, the heavyset Frederick Schmidt, jumped onto Howe’s head and shoulders, wrapping his arms around Howe’s neck. The noisy crowd below gasped, then quickly fell silent as Howe struggled to maintain his balance as his legs slowly bent beneath him. Every muscle in his body fought to stay rigid beneath the new weight he held.

Below, members of Ladder 7 hurried a portable ladder into position. The window belched another sheet of flame and smoke that enveloped Howe and his charge. Losing his grip of the lintel, Howe clutched Schmidt close; the fence points below sharp in his mind. Inside, Pearl dug his legs into the wall beneath the window, forcing his muscles to find an anchor as the weight of both men threatened to pull them all to the ground. They remained in this perilous situation for several agonizing seconds – Howe trying to straighten himself and pull the heavy man upright, the man straining to maintain a hold of the fireman and Pearl inside the building using his knees and waist as a lever hoping to overcome the pull of the two men dangling in his grip.

Below, firemen raised the ladder close to the dangling victim. The ladder brushed his foot as it rattled against the building’s facade. Howe was still struggling to keep his balance and Pearl’s last ounce of leverage all headed in the same direction. Suddenly, the tangled mass of firemen and victim moved slightly back toward the building. Sensing this subtle change, Pearl summoned all of his strength, pulling his massive arms and shoulders back with one sharp move.

Like a slingshot the heavy Schmidt flew toward Pearl, crashing through the remains of the upper-window sash in a shower of broken glass and splintered wood. He slid halfway across the room and watched as Pearl pulled Howe safely into the room.

The two exhausted firemen looked at each other. “Hurt?” asked Pearl.

“Nope. Sick with the smoke,” Howe answered, bent at the waist from exhaustion.

“I’ll call the ambulance for you and this fat fellow – he seems kind of done up too,” Pearl said, walking his partner toward the stairs.

Back to work

Howe’s stay in the hospital was short. He soon was back driving Ladder 7. Four days after the Lexington Avenue fire, Ladder 7 rolled up to blazing store on Fifth Avenue. It was Wednesday night, Jan. 6, when Howe rushed up a ladder to the top floor and plunged into the thick smoke. Searching under extreme conditions, Howe found an unconscious man and dragged him back to the window. Howe wrestled the man onto the ladder and carry him down to the street. Howe’s name was placed on the Roll of Merit for the second time in a week.

On May 26, 1898, Howe and Pearl were called to the office of Fire Commissioner John Scannell on East 67th Street. Pearl was awarded the James Gordon Bennett Medal and Howe, recently promoted to assistant foreman (lieutenant) and assigned to Engine Company 21, received the Hugh Bonner Medal for their rescues on Lexington Avenue.

One of the most devastating fires ever faced by the FDNY occurred on St. Patrick’s Day 1899. Thousands of excited spectators lined Fifth Avenue. Inside the Windsor Hotel, a man lighting a cigar while watching the parade accidentally set fire to lace window curtains on the second floor. Within moments, flames were racing upward throughout the building. The initial alarm was transmitted at 3:20 in the afternoon. Before fire companies could work their way through the crowds, the interior stairs were a mass of flames. Firemen swarmed across the front of the seven-story hotel, rescuing people by using aerial ladders, portable ladders and scaling ladders. Despite the best efforts of the fire department, the building began to collapse 20 minutes after their arrival. This horrific took the lives of 45 people. However, some of the FDNY’s most daring and spectacular rescues were made at this fire. Among those singled out by Battalion Chief John Binns in his report was Howe, who reportedly he saved at least eight people.

To the top floor

The city was blanketed with snow on Feb. 17, 1900, when a fire broke out in a five-story building at Fifth Avenue and 34th Street. Just as a member of Engine 26 completed a scaling ladder rescue of a woman from a top-floor rear window, a man, William Aiken, became visible trapped at a top-floor front window with smoke pouring out around him. Deputy Chief Thomas Ahearn saw the man and ordered Howe to get him.

Howe charged up the stairs of the building next door and hurried to the window next to the trapped man. Two policemen held Howe’s arm as he stood on the windowsill and leaned toward Aiken. Grabbing the man, Howe helped him up onto the windowsill as smoke and heat swirled around them. Pressing Aiken close, Howe drew him across to his building and with one pull into the safety of the top-floor window. Howe was once again placed on the Roll of Merit.

Nov. 11, 1902, saw the FDNY operating at a very unusual fire. Wooden scaffolding surrounding the unfinished Williamsburg Bridge caught fire and quickly spread upward. Reports of men trapped above prompted Guerin, now a chief, to send Howe, now captain of Ladder 6, and his firefighters to climb up and find the men. With flaming debris and chunks of molten metal raining down, they worked their way up the red-hot tower. After a torturous climb, they reached their objective only to find the extending flames below had cut them off. The wooden ladder they had been climbing moments before was now ablaze. Below, Guerin and the members of Ladder 18 scrambled to raise another ladder toward their trapped friends, while on the river below the crew of the fireboat Boody aimed a rope rifle above the trapped men and fired a perfect shot over their heads. The lightweight rope fell across the trapped men and they quickly hauled up the heavier rope attached to it. On the shore a huge crowd that had gathered to watch the fire burst into applause as Howe and the trapped men used the rope and the newly placed ladder to climb down from their dangerous perch.

The firefighting continued, but with great difficulty. The extreme heights caused hoseline after hoseline to break under their own weight. The flaming scaffolding and footwalks around the bridge collapsed in flames to the streets below, sending firemen and civilians scurrying for cover. Teams of fire horses scared by the flaming debris bolted from the roadway seeking safer ground. Finally, after many hours of backbreaking work, the fire was out. The city sent engineers to examine the steel cables and the bridge’s main supports. Firemen and officers accompanied the inspectors as they made their rounds, concerned about the inability to effectively deliver water to the upper sections of the bridge.

The following year, on June 18, 1903, Howe was placed on the Roll of Merit for heroic actions for the ninth time. Six months later, on Jan. 1, 1904, he was promoted to battalion chief.

Great Baltimore Fire

It was at 1:40 A.M. on Feb. 8, 1904, when the telephone next to Howe’s bed rang. The call was from the acting chief of department, Charles Kruger.

“Is that you, Howe?” Kruger asked.

“Yes,” Howe replied.

“Howe, you are ordered to proceed at once with the companies and apparatus that I designate to Baltimore.”

“What’s that? Baltimore? Where?” Howe rubbed the sleep from his eyes.

“Listen to me,” Kruger continued. “There is a big fire raging in Baltimore and the mayor of that city has appealed to Mayor McClellan for help from our department…”

With that, Howe was dressed and out the door heading toward a special ferry boat waiting at Liberty Street that would carry the companies to New Jersey, where a special train waited to take them directly to Baltimore. Nine flat cars carried seven gleaming steam fire engines, several hose tenders and a hook-and-ladder truck, all lashed down securely. Two cars were filled with 35 horses. Two coaches were for Howe and his 85 men and 10 New York City newspaper reporters. Several other companies followed later on another train.

The following telegram was sent to the mayor of Baltimore:

Robert M. McLane, Mayor, Baltimore, Md.

Nine fire engines and one hook and ladder company shipped to you on 6:34 o’clock train this morning in charge of battalion chief. The city of New York extends heartfelt sympathy and puts itself at your service. I shall be grateful if you call on me for any assistance New York can lend.

George B. McClellan, Mayor

After some delays, the expeditionary force of New York firemen reached Baltimore. With the winds blowing hard from the northwest, they were sent to the southeast fringe of the fire line to try to stop the fire from spreading to a neighborhood of tenements, lumber yards, factories and icehouses.

Their position was on West Falls Avenue alongside Jones Falls and Dock Street. They moved the seven six-ton engines into position and fired the pumps to their full 1,200-gpm capacity. Numerous lines were stretched and the New Yorkers made a stand. With wind-driven smoke and heat pounding their position, they held their ground and drove back some of the fire. Working in conjunction with the Baltimore fireboat Cataract, the FDNY firemen held their position through the night. With little visibility, they worked continually, taking breaks company by company only to have a sandwich and a cup of warming coffee before returning to the lines.

Howe led members of Engines 5 and 27 in a dangerous attempt to keep the spreading flames from igniting a huge malt warehouse. With the help of reinforcements the line held and the flames were stopped. For hours, they flowed water across the smoldering ruins, helping to ensure the fire was extinguished. Finally, dirty, cold and exhausted, the New Yorkers were ready to go home. The fire was out – their duty was done.

After meeting with Baltimore City Chief August Emrich and accepting his personal thanks and praise, Howe told him, “This is the worst fire I have ever seen. There seemed to be no stopping it when we got here. It was in so many places at once. I don’t believe our men have ever had a harder fight.” Regarding the Baltimore firemen, he told reporters, “The men themselves in this city are plucky fighters and good firemen. The way they have stuck to this fight against awful odds proves that.”

Howe and the New York City firemen had won the admiration and respect of not only the citizens and politicians, but also the Baltimore firefighters and the other cities that responded and operated in Baltimore including Philadelphia, Annapolis, Chester, York and Washington, DC.

The exhausted New Yorkers, who had been awake and operating for more than 48 hours, finally boarded a train for the trip home. Sadly, one FDNY member, Engineer of Steamer Mark Kelly of Engine 16, contracted pneumonia and later died. Howe also became very ill after the Baltimore fire, but refused to go sick. He was finally taken to the hospital on July 10, 1904, suffering from acute inflammatory rheumatism. One notable visitor to the chief was William Aiken, who had been rescued from a fire by Howe three years earlier. After a brief stay, Howe’s condition improved and he returned to work.

It was not long before Howe was performing his heroic acrobatics once again. On May 10, 1908, he responded to a fire at 214 East 65th St. While companies were attacking the fire, two men became visible through the smoke trapped at a fourth-floor window. A ladder was quickly raised, but proved too short. Seeing one of the men climb out and dangle from the windowsill, Howe sprang into action. He dashed to the top rung of a ladder, grabbed the man by the legs and lifted him above his head, then lowered him down to firemen on the ladder below him. Still on the topmost rung, he repeated this feat of strength and balance with the second man. For his actions Howe was awarded a department medal.

Countless lives saved

Howe retired from the FDNY on Dec. 24, 1913 at 8 A.M. During his 25-year career, he saved the lives of countless firefighters and civilians. At the time of his retirement, he was the only member of the department to have been placed on the Roll of Merit 10 times. A fireman from Ladder 10 who worked with Howe for years said, “Johnny Howe has a record of rescues and brave acts in times of danger as long as your arm. He is one of the most modest men in the department, and for that reason only has three medals. If he were to tell of all the brave things he has done, he would have to get two shirts to keep all his medals on.”

Howe died at his home on East 93rd Street on Nov. 17, 1917, at the age of 44.

—Paul Hashagen

About the Author

Paul Hashagen

PAUL HASHAGEN, a Firehouse® contributing editor, is a retired FDNY firefighter who was assigned to Rescue 1 in Manhattan. He is also an ex-chief of the Freeport, NY, Fire Department. Hashagen is the author of FDNY: The Bravest, An Illustrated History 1865-2002, the official history of the New York City Fire Department, and other fire service books.

Connect with Paul

Website: paulhashagen.com

Facebook: Paul Hashagen-author

Billy Goldfeder

BILLY GOLDFEDER, EFO, who is a Firehouse contributing editor, has been a firefighter since 1973 and a chief officer since 1982. He is deputy fire chief of the Loveland-Symmes Fire Department in Ohio, which is an ISO Class 1, CPSE and CAAS-accredited department. Goldfeder has served on numerous NFPA and International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) committees. He is on the board of directors of the IAFC Safety, Health and Survival Section and the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation.