The RESPOND System for Emergency Operations

Emergency operations are complex events that demand the full attention of responders. The myriad details, policies and procedures, rules and regulations, standard operating guidelines/procedures (SOGs/SOPs) and professional standards to consider can easily overwhelm and even confuse responders. On top of all of this, when infrequent events with no discretionary time (think Gordon Graham’s low-frequency/high-risk events) occur, responders are hard-pressed to remember what to do and in what order.

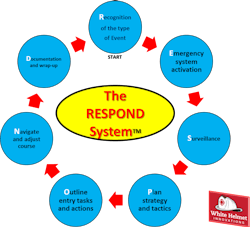

While several response protocols aimed at tactical objectives have existed for close to 60 years, most responders would be challenged to recite the steps, in the correct order, to function well at any type of emergency. However, there is an overarching and simple response guideline, in the form of a mnemonic device that can greatly assist responders in applying basic principles at every emergency, all with the goal of safely responding. This mnemonic—in this case an acronym—ensures a systematic and consistent response: RESPOND!

The RESPOND System explained

RESPOND stands for:

- Recognition of the type of event

- Emergency system activation

- Surveillance

- Plan strategy and tactics

- Outline entry tasks and actions

- Navigate and adjust course

- Documentation and wrap-up

The RESPOND System is based on years of experience concerning what needs to be considered in a systematic, step-by-step, chronological format in order to handle an event safely from start to finish. The system holistically identifies first-things-first and proceeds logically to an incident’s conclusion.

Within its framework, the RESPOND System contains the science of system operations as developed over 60 years ago by Dr. W. Edwards Deming. This can be looked upon as the operating system for emergency response that enhances responder safety by focusing on continual improvement. Use and practice with this system creates a culture of problem-solving and critical thinking. If done properly, this system helps responders avoid “analysis paralysis” or the even more dangerous “ready-fire-aim” approach because clear and concise goals and objectives can be identified and met.

Within the structure of RESPOND is the “plan-do-check-act” cycle developed by American physicist Walter Shewhart and popularized by Deming (as it is also known as the “Deming Cycle”). This process is the heart and soul of the continuous improvement component of RESPOND and is very similar to the “APIE” process (Analyze-Plan-Implement-Evaluate) used by numerous agencies.

Finally, the RESPOND System relies on the use of checklists to help responders in emergency event situations. Dr. Atul Gawande’s book The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right cites abundant data and case studies showing that the use of properly designed checklists as part of a systematic approach results in a substantial reduction in human errors and drastic improvement in overall outcomes. We strongly believe that the use of a systems approach, with simple guidelines and corresponding checklists, can prove to be an effective melding of best practices in emergency response.

Let’s now walk through each of the seven phases of the RESPOND System.

Recognition of the type of event

The first phase is recognition. The type of event can often be identified early on from dispatch information or what can be observed upon arrival at the incident. Recognition is largely a matter of awareness, but it is also important to remain flexible until more incident information can be gathered.

Upon receipt of an alarm, responders usually pick up what type of emergency has occurred and mentally prepare for what is needed even before they leave the station. As more information is relayed en route, more mental preparation occurs. Recognition of the type of event can easily happen in times of natural disasters, traffic collisions, EMS emergencies, fires, hazmat releases and terrorism incidents. The recognition factors may not always be readily apparent, however, and responders need to be vigilant on all calls. Sometimes the true character of the event may not be revealed until arrival on location or after more information is gathered.

Another factor to consider with the recognition phase is knowing when to tune into your “fight or flight” response. In other words, your recognition may lead you to react by fleeing the area or, conversely, not entering it at all, based on responder safety. For instance, a large tank fire involving propane presents a recognition challenge of knowing what is involved and the hazards if you stay in the immediate area. Likewise, in a fire situation where a fully involved structure is found, entry may be ill-advised based on both the victim’s profile and responder safety concerns. Based on resources and response capabilities, you may decide to stay and confront the problem. Or you may decide to react by rapidly backing away and taking a safe and defensive approach.

Much of the first phase of recognition is intuitive and may even be felt on a gut level. Responders can tune into this visceral feeling by being more conscious of what their gut is telling them. Psychologist Gary Klein found this to be true when he studied experienced fireground commanders and how they decided their actions at fire scenes. In his now famous work, termed Recognition-Primed Decision-Making (RPDM), Klein found that these commanders had a gut-level response to viewing fire scenes that they responded to intuitively. In other words, their subconscious picked up on what they were seeing, feeling and thinking, and provided a suitable match in their mind’s eye on what to do based on their previous experiences.

Emergency system activation

Based on your recognition of the event, you can relatively quickly decide if it is a true emergency or merely a scenario that needs prompt service from emergency responders.

If the incident is not an emergency, then appropriate personnel with the skills and equipment needed for mitigation can handle it. In these cases, no further resources are necessary, and the needs of this step are met.

If it is an emergency, this step of the system prompts the initial incident commander (IC) to request the additional resources that will be necessary to match the problem at hand. Notify your command or communication center of the type of incident you are confronted with and set up your own agency’s response system appropriately. That entails following your own SOPs/SOGs for establishing your incident command system, coordinating the event and providing an effective initial radio report (based on information gleaned in your “Recognition”).

Get the ball rolling effectively by controlling the event safely and communicating with all other responders. This means providing a comprehensive size-up and properly delegating tasks at the scene. It also means being aware of the weather conditions, setting up safety zones (Collapse, Hot, Warm and Cold), controlling traffic the best you can, being aware of possible explosion impact zones, and possibly evacuating danger areas and downwind areas of contamination due to toxic smoke or hazmat plumes. It is also important to remain flexible at this point and not overcommit resources. Hence, the overall posture at this point should still be defensive and highly analytical.

Surveillance

Surveillance entails gathering more information through concerted observation of pertinent clues and available sources. Collect and document information from witnesses on or near the location of the incident. Be sure to query what they saw, smelled or felt. The most important task here is to positively identify the nature of the event or what is involved. This task alone is quite often very difficult early in the incident, especially in a defensive mode, because it may not be possible to get near enough to the problem area and still retain your safety. It is also important to do a 360-degree check around the hot zone (structure or otherwise) involved to better size-up the magnitude of the event.

During the course of your surveillance, be mindful of your risk/benefit profile in your choice of vantage points and investigation tactics. In other words, gather information at a risk level that is safe. Surveillance can also be gathered through reconnaissance or “recon” teams dressed in appropriate PPE. These recon teams of two or more responders should wear, at a minimum, structural firefighting protective clothing and SCBA, and should only attempt to attain information from a defensive posture. Forward-thinking responders are now utilizing drones to capture scene information.

Remember to capture information for documentation purposes and to use for decision-making. Part of the surveillance phase may involve research once the problem is identified. This is especially the case involving highly specialized hazards, such as thermal, radioactive, asphyxiation and acoustical, chemical (including explosives), etiological/biological and mechanical (TRACEM) hazards.

Plan strategy and tactics

Based on the information gathered and the research conducted, a working plan can be formulated to handle the emergency. At this point in the response, you should be starting to get your arms around what has happened, where the event may be going, and what to do to stop or minimize its aftermath.

Combined with an honest (and earnest) risk/benefit analysis, your strategy should be chosen (offensive, defensive or marginal). With strategy come your overall incident objectives that will be used to define how you intend to mitigate this event. Strategy and objectives will drive your tactics—the “boots on the ground” actions that are needed to stop the problem.

All of these decisions should be written in your incident action plan (IAP) and communicated at a briefing with all involved parties. This may be accomplished via radio on smaller, fast-moving incidents, such as structure fires, or this may involve fully developed command structures and multiple planning meetings if you are handling a long-term incident. Also, if dealing with hazardous materials, within the plan should be decisions regarding whether personnel should be offensive vs. defensive posture as well as what measures are needed to control the product that is released. Will operations use confinement vs. containment measures? And, will control measures be physical or chemical or a combination of both?

Strategic concerns entail life safety, incident stabilization, and property loss conservation efforts—better known as incident priorities. This phase deals with what must be done in terms of overall plans and incident goals and the scope is broad in nature. Tactics support strategy and detail how things will get done, specific functions and actions that need to occur, and are, consequently, very specific in nature.

Some of the tactical systems below have been used for decades and have even served as strategic models. Some are only a few years old and now entail many of the actions revealed through National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and UL research. Regardless of the system used, they all fit into this fourth phase of the RESPOND System.

Tactical concerns support strategies and can include these firefighting related tactical models:

- RECEO VS (Rescue, Exposures, Confinement, Extinguishment, Overhaul, and Ventilation and Salvage). Model by Lloyd Layman/1950.

- REVAS (Rescue, Exposures, Ventilation, Attack, Salvage). Model by On-Guard/1982.

- PREVIS2-OS (Perimeter, Rescue, Exterior Attack, Ventilation (positive pressure), Interior Attack, Search-Primary/Secondary, Overhaul, Salvage). Model by Richard Mueller/2013.

- SLICE-RS (Size-up, Locate the fire, Isolate the flow path, Cool from a safe distance, Extinguish, Rescue, Salvage). Model by ISFSI/Eddie Buchanan/2014.

- DICERS-VO (Detect, Isolate, Confine, Extinguish, Rescue, Salvage, Ventilation, Overhaul). Model by Lt. Ray McCormack/2014.

Tactical models for specific events, such as hazmat or terrorism, also exist:

- DECIDE (Detect hazmat presence, Estimate likely harm without intervention, Choose response objectives, Identify action options, Doing the best option, Evaluating progress). Model by Ludwig Benner, Jr./1973.

- 8-Step Process (Site management and control, Identify the problem, Hazard and Risk Assessment, Select PPE, Information Management and Resource Coordination, Implement Response Objectives, Decontamination, Terminate the Incident). Model by Gregory G. Noll, Michael S. Hildebrand/1978.

- GEDAPER (Gather information, Estimate harm, Determine strategic goals, Assess tactical options and resources, Plan of action implementation, Evaluate operations, Review the process). Model by David M. Lesak/1998.

Outline entry tasks and actions

These tasks are the hands-on activities that are needed to satisfy the tactics that have been identified. Tasks at fire scenes are numerous and varied and must be carried out in a safe and expeditious manner. The appropriate level of PPE should also be identified with respect to the mission.

Tasks at special events can be written in the IAP, but at a minimum they should be included in the responder briefing before any entry activity. As part of any plan, there should be provisions for unexpected events, spelling out what personnel actions should be. Also, as the incident progresses, adjustments to strategy, tactics and tasks can be completed with an updated IAP. With all of this, communication is the key!

An important task to consider after exiting the fire scene where combustion products or other types of contamination exist is that of cleaning gear and equipment and personnel. This consideration is important in order to reduce or eliminate the hazard from migrating from the fire and/or release area to other areas. Therefore, any object, people, equipment, animals, supplies, etc., must be assessed for possible contamination before it leaves the hot zone or fire scene. If this is not done, contamination can wreak havoc by spreading uncontrolled. Contamination can cause illness and may be manifested in diseases, such as cancer. It is essential that the modern firefighter be aware of this fact and exercise good hygiene after every firefight by promptly decontaminating their PPE at the fire scene, seal it in secure bags for cleaning it later in a controlled manner, and also promptly cleaning themselves, especially vulnerable skin areas such as the face, ears, neck and wrist areas with disposable towelettes at the scene. Back at the station, fire personnel should shower thoroughly, redress in clean clothes, clean their dirty clothes before taking them home, and place their back-up PPE into service.

At special hazard events, most often everything that leaves the hot zone should go through a formal decon corridor in the warm zone and be cleaned at least in a rudimentary way (i.e., a general water rinse followed by a soap solution scrub, then ending with another rinse). For the most part, this will address the majority of the contamination. All of this should be the general rule for all personnel who enter and exit the contamination area, and include vehicles. Mass decon for large numbers of people warrant an adjustment to the decon process in that a physical scrubbing may be impossible. The general mindset for mass decontamination must be “do the most good for the most people, in the quickest way.”

Navigate and adjust course

Jack Welch said it best: “Change before you have to.” The Navigate step mandates a constant state of situational awareness and adjustment of strategies and tactics to match evolving incident conditions. It may be the most important step in the RESPOND System in that if it is skipped, one-time correct strategies and tactics may turn into catastrophic events and responders not going home. Loss of situational awareness and failure to adjust strategies and tactics is one of the leading contributors to non-medical-related line-of-duty deaths for first responders.

Some items to consider in maintaining your situational awareness include:

- Unexpected results from standard tactics: If you anticipated that the situation should have improved by now, and it hasn’t, it’s time to make a change.

- Incomplete information: While there is always a certain degree of unknown information on the front end of every incident, things normally become clearer as the incident progresses. If this is not happening, consider a change.

- Outliers: These are the pieces of information that don’t fit into the rest of the data collected (i.e., the “nothing showing” alarm in a big box store with clear conditions inside but a massive fire in the void space between the drop ceiling and the roof). Whenever a piece of data doesn’t fit the overall picture, the natural reaction is to dismiss it. Be ever diligent of the outliers!

- Tunnel Vision: Successful navigation requires a constant view of the overall situation, not just the main part of the problem.

Navigating a plane, ship, car or emergency incident requires that the person behind the wheel (the IC) is constantly aware of the current situation, expectant of certain waypoints along the course of the journey and proactive in changing course as necessary. Essentially, this is the check and act segments of the Deming Cycle mentioned earlier.

Documentation and wrap-up

After the emergency phase is complete, responders need to gather all the information from the event for documentation purposes. For record-keeping, it is imperative that the following questions be answered: Where did the incident occur? When did it occur? Who did it involve (both responders and others)? What happened and what were the chain of events? What were the actions of responders? How did the incident occur? Why did the incident occur? All data and information surrounding these questions should also be recorded. All of the answers are important for several reasons, including legal concerns, reimbursements, compensation issues, employee pay, safety, and case study and lessons learned for review purposes.

Wrap-up concerns should identify who will take over after the emergency phase has ended. It also identifies who is responsible for what aspects of clean-up and mitigation. It can be used to review the incident operations in order to learn and make improvements and the lessons learned can be channeled into future training sessions. Essentially, this final phase is the feedback loop that all comprehensive systems have in common. By looking back through each phase of an event with a critical and constructive eye, improvements can made for the next event.

In sum

The RESPOND System is based on experience and is pragmatic in nature. Easy to learn and remember, it can be used generically for any type of event because all emergencies have commonalities of response. It can also be customized to work for specific types of emergencies, such as firefighting, mass casualty incidents, technical rescue, SCUBA, and hazmat or terrorism incidents. It has been developed to ultimately operate from the start to finish for an emergency, with responder safety paramount in its design, but it has a broader, strategic, all-inclusive overview. Like any system or model, the success depends on responder knowledge of its operation and their comfort level in using it. Attention to emergency complexities can be better handled through the use of the RESPOND System.

Joseph L. Krueger

Joseph L. Krueger, MS, MIFireE, CFO, EFO, is a 34-year veteran of the fire service and is currently a deputy chief with the Greater Round Lake Fire Protection District in Round Lake, IL. He has a master’s degree in executive fire leadership and disaster preparedness from Grand Canyon University and a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Illinois-Chicago. He is also a graduate of the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program. Krueger is a member of the Institution of Fire Engineers and has a Chief Fire Officer designation. He also has extensive experience in leadership and management in the private sector and is a principal partner of White Helmet Innovations, LLC.

David F. Peterson

David F. Peterson, MS, EFO, is a 35-year veteran of the fire service and a retired Wisconsin fire chief. He is currently a fire training coordinator for Blackhawk Technical College in Janesville, WI. Peterson has served as a company officer, training officer, hazmat team leader, chief officer and incident commander. He is a past board member for the Wisconsin State Fire Chiefs Association, a national presenter on fire service and hazmat topics, and he founded the Wisconsin Association of Hazardous Materials Responders in 1992. Peterson has a master’s degree in executive fire leadership and disaster preparedness from Grand Canyon University and a bachelor’s degree in fire service management from the University of Southern Illinois. He is also a graduate of the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program. He is a principal partner of White Helmet Innovations, LLC.