'Into the Fire' Aims to Build Support for Firefighters

Oakland, Calif. firefighter Zac Unger stares into the lens with a grin from ear to ear as he talks about the importance of a well-aged helmet.

"Guys show off their helmets that are old and crusty," he says. "It's the worst thing in the world to have a brand new coat and a helmet that's all shiny and doesn't have any ash on it.

"You want to be able to show that you've been in there and you've taken the hit and taken the beating.

The camera switches its focus to Washington, D.C. firefighter Tomi Rucker, who helps shed light on the myth that rookie firefighters find their own ways to damage their helmets so not to be picked on.

"I used to think it was just a joke, until one day I came in and the rookie on the fire truck was sticking his helmet in the oven," she says. "I was like, 'What are you doing? We catch fires.' "

Unger and Rucker are just a few of the many faces featured in new documentary "Into the Fire" that has managed to humanize firefighting through the stories told by personalities from departments across the country.

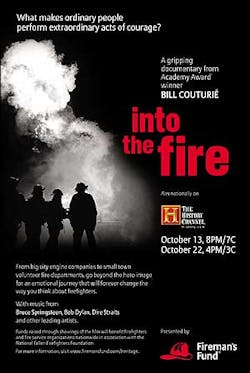

The one-and-a-half hour film -- set to air on The History Channel Oct. 13 at 8 p.m. -- was produced by the Fireman's Fund Insurance Co. with the goal to increase the nation's familiarity and support of firefighting, according to the company's Web site.

Fireman's Fund, which launched the film as part of its Heritage program, says it will donate funds raised through screenings of the film to firefighters and fire service organizations in association with the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation.

At the reigns of the project was director Bill Couturie, who has directed several war documentaries including "Last Letters Home: Voices of American Troops from the Battle fields of Iraq" and "Dear America: Letters Home from Vietnam." This was Couturie's first work with firefighters.

"I've done a lot of films about soldiers and war, and I'm just constantly amazed that there are people in the world who are willing to put their lives on the line, to sacrifice their lives, for us," he says in a trailer for the movie. "When the opportunity came along to do a film on firefighters, I hadn't really though about it, but it's like, 'Gee, these guys do the same thing.' "

The film's crew conducted interviews at departments in California, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, Washington, D.C. and Wisconsin, and came away with heartfelt accounts from 13 firefighters on life in the fire service.

The camaraderie among firefighters is obvious through the movie, and in a one segment, nicknames like Amigo, Doc, Cowboy, Big Dog, Uncle, Axe Head and The Fuzz are shown emblazoned on the tops of lockers. Many of the firefighters in film show pride in their nicknames, no matter how ridiculous they may be.

"You might not like your nickname, but the fact that someone gave you one means that they care enough about you to have thought of one," Unger says.

Michael Perry, a volunteer from New Auburn, Wis., refers to his fellow firefighter's nickname: Bob the One-Eyed Beagle. The name was given to a member of the department who is cross-eyed.

"People say that's very insensitive," he says. "I'm like, 'No.' In this group you need to get nervous if they're not making fun of you. If they're being really nice to you and polite, it's a bad sign."

The film also touches on a lot of misconceptions people outside of the fire service have about the work, including the misconceptions one has when becoming a firefighter.

"You show up for your first fire and it's everything you hoped it would be," Perry says. "The pager goes off, you run to the building and you get the big shinny trucks and turn on the flashing sirens and you go out and there are big flames and you spray water and knock it down and it's all very glamorous and exciting.

"And then, oh, you got three hours of clean up. You've got to rip apart soggy walls and pull out wet insulation. That's not much fun anymore."

Glendale, Calif. Fire Captain Niall Foley recalls a mistake he made as a rookie while fighting a fire from a building's roof.

"I'm the rookie so I'm towards the back," he says. "I can't see anything. All I can see is the guy in front of me. … There's a reason you walk in line, there's a reason you sound out in front of you. There's a reason for all of that and you know all of this in your head, but you're the new guy, you want to prove yourself, you're all excited.

"So we're walking in a straight line, everyone is sounding out, and I can't see. I took one step out of 'in line' and put my leg though the roof."

Perry described a fire department as one big family, and that when someone messes up, they'll hear about it.

"The number-one game here is ego-deflation," he says. "If you mess up you should print up a press release and make sure everyone gets a copy, because the only thing worse than them hearing about it is them finding out about it about a week later."

Unger compares the scenes from Hollywood blockbusters such as "Ladder 49" and "Backdraft" where firefighters are shown heroically busting into buildings and making effortless rescues.

"Fire is totally chaotic," he says. "Mostly you're just stumbling through. It's like someone took a wet towel and put it over your head."

In one of the final segments of the documentary, the 9/11 terrorist attacks are profiled as viewers are reminded not to forget the sacrifices made by firefighters that died day and by firefighters across the country everyday.

One of the main goals of the film is to help raise funds to help purchase equipment such as thermal imaging cameras, a device featured in the film, for departments that can't afford them. Couturie expresses the need for support of fire services so that firefighter deaths are prevented.

"Often times they die for us," he says. "They shouldn't have to die for us. They should have the resources, the manpower, the training and the equipment they need to do their job and then go home to their families."

Related Stories