Meth Labs Posing Threat To Missouri Firefighters

"Honestly, I am scared by the situation," St. Gemme told the Public Safety Committee of the Park Hills City Council. "It is serious business."

The fire chief told the panel that members of his department have had only minimal training about what to do if they encounter a meth lab. Some members have gone through the same basic course two or three times, but he does not feel the training thoroughly prepares firefighters for the situation.

St. Gemme added that he is not aware of any advanced training that is readily available for members of the fire service.

Holloway and St. Gemme met with the committee at the request of its chairman, Councilman Mike Glore. It was Glore's desire to see if the two departments have the necessary protective gear and training to safely deal with the illegal meth-making operations.

According to Holloway, Detectives Mark Rigel and Mike Kurtz are trained and certified in dealing with meth labs. He said they also have the protective gear that state and federal agencies recommend be worn when dismantling a lab.

Until Tuesday, the two detectives were the only officers in the department who had that gear. Holloway said that is changing, thanks to a program arranged by the Missouri Police Chiefs Association in cooperation with the State Emergency Management Agency.

Holloway and Lt. Doug Bowles went to SEMA headquarters in Jefferson City and picked up 16 sets of the protective gear. It is being provided through Homeland Security grants made to the state.

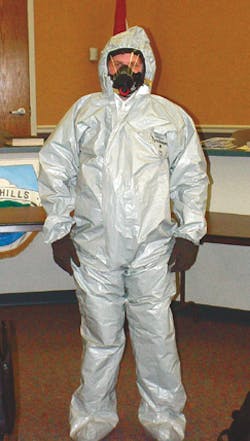

Each set of gear is complete with hood, breathing apparatus, a plastic-like suit, and feet covering. The gear is contained in a case that officers will be able to carry in their patrol cars.

Holloway said each officer will have to go through five hours of training SEMA will be providing. It is not the advanced training on taking down meth labs, but more of a course on self-protection from the hazards encountered with those labs.

Even with the training, Holloway indicated other officers will not be taking down meth labs on their own. That will still be done only under the direct supervision of the two detectives trained for that purpose.

The new protective gear is disposable, good for only one use except for the breathing apparatus. It is intended not only for meth lab scenes, but any other bio-chemical situation the police might encounter.

The police chief also suggested to St. Gemme that he arrange a training session for members of the fire department that can be provided by Rigel. In a three-hour session, most of the more important points can be covered.

St. Gemme said over the past few years members of the fire department have responded to a fire call and discovered there is a meth lab on the premises.

"A lot of times we are there before the police and don't know what we are getting into," St. Gemme said. "It basically scares the hell out of you."

It is fire department policy that as soon as it is determined there is a meth lab -- or anything else that might make it a crime scene -- the firefighters pull out and call for the police. At that point, St. Gemme told the committee, the fire department is there for back up and it is the police department's scene.

While there is the hazard of explosions with some types of meth labs, the most common concern is exposure to toxic components used in making the illegal substance. Even though many of them are common household products, there are some that can cause extremely serious respiratory problems as well as skin and eye irritation.

Members normally wear breathing apparatus and bunker gear when entering a structure where a fire has been reported, St. Gemme said, but the bunker gear is not really designed to fully protect them against toxic chemicals.

When they respond to medical emergencies, firefighters generally do not enter wearing a breathing apparatus. It is not generally considered necessary, St. Gemme said, and it would tend to frighten or excite some people for whom emergency medical attention is necessary.

At the same time, Glore said, it is possible that people who have been making meth might call for medical assistance if they experience respiratory problems or burns. Then, the councilman noted, firefighters and ambulance personnel could encounter the same hazardous circumstances.

It was confirmed by St. Gemme that his department has encountered the situation that Glore described.

"So far as I know, none of our members have breathed any of that stuff," St. Gemme said. "We hope not, but sometimes the real long-term effects are not discovered right away."

While Holloway said he feels comfortable with the protective gear his department now has, the committee suggested St. Gemme look at the situation and see if there is anything the fire department should have.

Councilmen Tom Reed and David Easter joined Glore in saying they want to be certain that the city provides everything it can to protect both the firefighters and police officers in dealing with meth labs.

The city is also looking at making changes in its housing code to protect people from properties that have been contaminated by operating meth labs. There is growing concern that long-term contamination can create serious health hazards to subsequent occupants of houses, apartments and trailers in which meth has been manufactured.