Allow me to introduce myself: I am the son of retired Deputy Chief Jim Smith. Since this issue of Firehouse Magazine includes his final “Fire Studies” column after 34 years, I wanted to recognize him for all of his accomplishments throughout his fire service career. He had no idea that this article was submitted, and he is too humble to knowingly allow it.

My thought process for writing this article is that we always honor and admire our leaders after they’re gone and it’s too late for them to enjoy the recognition. I just wanted to try and tell Dad’s story from a different perspective.

I believe that the best way to honor someone is to know the person before we speak of any accomplishments. Dad was the second oldest of 11 children. As Dad says, “We were poor, but we just didn’t know it.”

With so many mouths to feed, Dad worked at Sears, Roebuck and Co. as a teenager to help with costs around the house for his parents. He was lucky enough to land a firefighter position with the Philadelphia Fire Department (PFD) at the young age of 19.

Being hired in 1966, Dad experienced many fires that resulted from the civil rights riots that occurred in the 1960s. This, along with less stringent building codes, led to a very heavy fire load for a new firefighter. He always says that as fast as they could “take up” from a fire scene there was another fire pending that they could respond to. “If we messed up on a fire, we just fixed that mistake on the next call.” The workload of this generation has been unmatched since.

It was at this time that he started to hone his craft of firefighting. As noted in Dad’s article, “A Wealth of Knowledge Garnered and Shared,” he progressed rather quickly through the promotional ranks.

So, as a teenager, I found myself in the midst of watching from behind the scenes my father (my hero) weave his craft. No, I didn’t have the ability to watch Dad at work or on the fireground. Honestly, I never even saw him at the firehouse until I was old enough to drive myself there. Dad always worked across town in the busier sections of Philadelphia.

What I witnessed at home was a guy who was totally immersed in his profession. In the early-to-mid-1980s, my father was pounding away on Apple computers in his office. For a baby boomer, he was rather tech savvy. Those Apples were just the beginning of what would seem to be an endless line of computer purchases. Dad would wear out the keyboards on the laptops.

When he studied for promotional tests, I recall leaving for school in the morning and returning home after school and he still was in the same chair studying. The old adage that hard work pays off was definitely fitting for Dad!

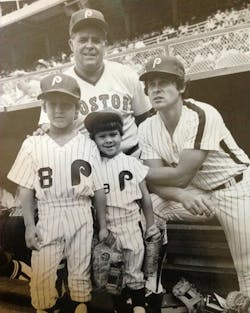

As a 10-year-old, I remember being at Veterans Stadium to watch the Phillies play. I remember seeing two kids about my age in full Phillies uniforms on the field. It was Bob Boone’s sons (Bret and Aaron). I always was envious of them being able to hang out in the locker room.

As I noted earlier, I didn’t go to the firehouse as a kid, but as I got older, I realized the success my dad had achieved within the PFD and throughout the country. Dad was driving and flying anywhere and everywhere to those who wanted him to speak to their department. When I became a firefighter myself, I realized that I was one of only a few firefighters in the country who had a father with the knowledgebase and experience that my dad had achieved. In some ways, I feel like Bret and Aaron Boone. As they did, I followed in my father’s profession. I did my best to absorb his lessons and to listen every chance that I could. I never used Dad’s name to help advance in my career. Being in a civil service town, my blood relatives didn’t matter. I was promoted on my merit and being the top candidate on the promotional list. However, I certainly utilized the knowledge and experience that was handed down to me from my dad. At times, we compare notes from our different generations, but “people problems” still seem consistent. His guidance and support is always reassuring and helpful. While always a huge supporter, he would give me counter perspectives as well, which I always appreciated.

I remember it to be commonplace for Dad to leave for the National Fire Academy for a week at a time. Many of the courses spanned two weeks, but he would make the two-and-a-half-hour drive home for the weekend. I still remember carrying milk crates of materials out to his truck ahead of his trip. What I didn’t realize at the time was that I was watching a future hall of famer. Dad never half-assed anything. He was all in whenever he took on a task.

Dad decided one day that he wanted to write a book about firefighting. He immersed himself in this task, just as he did with everything else: 1,000 percent all in. It wasn’t easy nor did it happen overnight. However, he created an excellent book about strategy and tactics on the fireground. It was Dad’s inclusion of personal stories and breaking down complexities to the most basic level that endeared me most to his book. In its fourth edition, it shows that it was a winning combination.

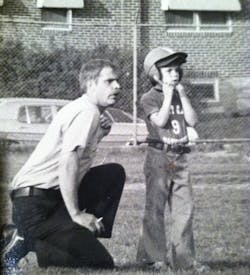

Dad always has been there for us as a family. He was involved in the local playground sports and coached me all through school. No matter the location, Dad was at the game, and I could hear his voice without ever having to see him on the sideline.

My sister, Colleen, and I had a wonderful upbringing thanks to Mom and Dad. They provided us with love and compassion and instilled a strong value system for us to follow. We both count our lucky stars to have such wonderful parents. Dad also has been there for the other members of his family. He has helped many of his siblings with advice and guidance over the years.

Behind Dad’s success was my mom, Pat, who supported him in every facet of their life. Through working multiple jobs, to buying a house that easily qualified as a money pit, to his constant travel across the country to lecture or to the NFA, Mom has toughed it out alongside Dad every step of the way.

To give an example of how humble Dad is, he didn’t even mention to us in 2016 that he was being recognized by Firehouse Magazine with induction into its Hall of Fame. He didn’t want to bother us. This was a prestigious acknowledgement by Firehouse for his long career. As a well-respected incident commander, national speaker, successful author, nearly 30-year adjunct instructor at the NFA, graduate of the Executive Fire Officer Program, 41 year-career at the PFD and 28 years with Firehouse Magazine, this was an important recognition. The experience in Nashville was incredible, and I’m glad that we were able to surprise Mom and Dad by showing up unannounced.

Through social media, I can see all of the retired members of the PFD passing away. The PFD is a microcosm of the fire service around the country and the world. This generation of firefighters, in my opinion, are dying off at a young age and most likely directly affected by their workplace exposures. When we talk about this generation of firefighters around the firehouse kitchen table, I liken them to our World War II veterans. We call our WWII vets the greatest generation, and that's what I am comparing the firefighters from the 1960s and 1970s to. These men not only fought this heavy fire load, but they were the generation that started to become the educational leaders of the fire service. Whether in the academy classroom, college classroom, national fire academy, lecture circuit, magazines, books or now online, these heroes from this era have passed down an incredible amount of knowledge to our entire industry. Part of the reason for wanting to write this article, besides honoring my father, was to acknowledge that we’re witnessing the end of an era. We have been fortunate to experience Chief Alan Brunacini with his innovations, insights and lectures. We need to value and absorb what the remaining members of this generation have to offer. Although these men are just a few, we must value the words of Chief/Superintendent Dr. Denis Onieal, Deputy Chief Vincent Dunn, Battalion Chief John Salka Jr. and Deputy Chief Jim Smith. This isn't meant to shortchange those leaders who followed after this generation mentioned above but rather to pay homage to those who saw fire on a more regular basis and to listen to their words of wisdom.

In the PFD, the battalion chief and deputy chiefs are assigned an aide to be their driver. These aides were more than just a chauffeur. The deputy chief’s aides helped to manage the staffing for their division (half of the city) as well as being the right hand of the deputy on an incident scene. No story about Dad’s career would be complete without mentioning Charlie Armstrong. (Side note: In Philly, Charlie is pronounced Cha-Lee. Don’t ask me why, but just know that everyone from Philly reading this is saying Cha-Lee every single time you say Charlie.) Dad first met Charlie on a cold fireground in 1976 and was introduced to him knowing that he was being transferred to Charlie’s company (Engine 20) as its new captain. Engine 20 is located in Chinatown and serves center city Philadelphia. As you can imagine, there was a strong mix of mercantile businesses, residences and high rises in center city. Dad and Charlie worked together for three years in this company. Charlie stated that there was something different about Smitty. “He knew every aspect of the job and was willing to explain it to anyone who would listen.” The weird thing was that “He was just one of the guys. His ego never got in the way. But there was no doubt he was in charge.”

When Dad became deputy chief in 1987, he asked Charlie to be his aide. Fortunately for all involved, Charlie accepted the assignment. Training was important to Dad, and he continued that value from the company level all the way through to the deputy chief level. Charlie provides great insight into how Dad operated. It wasn’t a “wait and see how things play out on the fireground” approach. Charlie paints the picture that Dad was like a game manager. I will liken him to New England Patriots Head Coach Bill Belichick, always prepared for every “what-if” scenario. If you weren’t able to execute your task, you heard from Chief Smith and you drilled on it to make sure that it didn’t happen again. If you did what you were supposed to do, you heard kudos for that as well. Over all of my years of hearing compliments about Dad (and honestly, there were too many to count), it was consistently stated that he was one of the best bosses to ever work for. I believe that it was his down-to-earth approach, honesty and consistency, meshed with his preparation and ability to forecast a problem and then verbalize the task that needed to be accomplished, that made him so good at his job. None of these traits are easy to master, but as a chief officer, to be able to attain all of these qualities, it's a recipe for success.

Charlie said that whenever transfers or promotions occurred, Dad would make it a point to speak with the new battalion chiefs and relay his expectations for all who were involved with the operations on a fireground. Dad valued having competent, knowledgeable personnel in the proper positions. He was preplanning with personnel well before the shifts even started. When responding to a fire as deputy chief, Charlie drove and Dad had his head down, writing every bit of information that was relayed over the radio onto a note pad. By the time that they arrived on scene, Dad had a very good understanding of the incident. Without hesitation, Charlie said, “Smitty had total control of an incident. He was the quarterback of the fireground.” Charlie stated that no matter the scene “Smitty was always, and I mean ALWAYS, under control. You never saw him panic!” In all of Charlie’s years with the PFD, he said there was “none better on the fireground.”

Charlie chuckled that Dad would talk a good game about ripping into someone for poor behavior, but, in the end, he was a nice guy and fair. He didn’t have it in him to be too mean. Charlie was awed at how people would react and flock to Dad when he was in his Class A uniform. At 6-foot, 2-inches tall, broad shouldered and sporting an impressive mustache, Dad had a presence about him. He certainly didn’t cower or hide. I can imagine that he owned every part of that persona, and it would draw people to him. Charlie was wise enough to forecast these scenes and divert Dad, so the media or others wouldn’t bother him.

What I haven’t shared to this point is Dad’s ability to cook and bake. As I mentioned earlier, Dad grew up poor. His mom was 100 percent Italian, and she could cook anything and everything. With 11 kids, one only can imagine that all she did was cooking and laundry. He clearly paid attention to the cooking part, laundry not so much. (As a side note, I talked him through his first ever, and only, load of laundry over the phone when he was about 60-plus years old.) Working the 10/14 four platoon schedule, Dad often would cook for the guys in the firehouse for night works. As a deputy chief, this was easier, as his run volume wasn’t as high as the engine companies. As stated earlier by Charlie, Dad didn’t have an ego and was one of the guys. He cooked dinner because he enjoyed it and it helped out the crew. Charlie said that he never saw a deputy chief regularly shop and cook dinner for the guys in his station. “Smitty was just different.”

After nearly 20 years working together, Charlie was family. He spent more time with Dad than we did. He knew everything that was going on in our lives, just as you would expect from a partner. I’ve talked to Dad countless times on every possible topic concerning firefighting. We’ve discussed the PFD basically every day. One thing that is consistent is the bond that he and Charlie had. Charlie tells a great story about how my dad once said, “You know, after all of those years together, we never had a fight or argument,” and Charlie replied, “Why would I want to fight with my best friend?” To me, that seems to sum up the relationship that Charlie and Dad had together.

When Dad was assigned to the 2nd Division, he and Charlie were about to leave their mark on the other half of the city of Philadelphia. Being stationed at Engine 70, he was to encounter a station that had some very young firefighters who had no idea how lucky things were about to become. Ironically, as I stated earlier, Dad worked at Sears prior to being hired with the PFD. Over the years, that Sears store was torn down, but Engine 70’s station actually was built by Sears and located on their vast property. The station still remains today, but it was the last station that Dad worked at before retiring in 2007. A young firefighter who made a big impression on my dad was Firefighter Matt Wnek. Matt is a true Philly guy who isn’t afraid of hard work. He was smart enough to constantly have conversations with Dad and applied the knowledge that was shared. Below is a write up from Matt from his time with dad at Engine 70:

In my 19-year career as a Philadelphia firefighter, I was lucky enough to start at Engine 70, “B” Platoon. Engine 70’s station is the deputy chief’s headquarters for the 2nd Division. The deputy chief who I had the pleasure to work for was DC Jimmy Smith (aka Smitty). As time went on, I began to form a relationship in which he became a mentor, coach and family friend.

Our relationship began in 2003 when housework started at 0900 hrs. I knocked on DC Smith’s office door asking if I could clean his office and bathroom. I introduced myself and exchanged pleasantries. He really wanted to know who I was. He asked about my history and my family. As we spoke, I could tell that he was being genuine, continuing to listen for about 15 minutes as I explained how I ended up joining the Philadelphia Fire Department. It was very relaxing to have a deputy chief of his status and caliber treat me with such respect as the new firefighter.

DC Smith mentored us young firefighters. I listened when he spoke. He talked about fires that he worked through his career, the good and the bad. He was humble enough to admit mistakes that were made on jobs and tried to teach me what he and others learned to make me a better firefighter. He never hesitated to answer any questions that I had. He still is always there for me and anyone who wants to make themselves a better firefighter.

On a lighter note, as firefighters, we always talked about what we were going to eat the four days together in the firehouse. In the firehouse, he was a frugal shopper. He always had the ShopRite circular on the first day of work, scouring for sales. He then would make a list of food for one of the members to pick up. He also would take his turn cooking in the firehouse. His specialty was cavatelli. The members referred to this as the "forearm workout" or "no wrist left dinner." DC Smith made his homemade cavatelli, or should I say the members made DC Smith’s homemade cavatelli. The other members and I would start to laugh when we would come into work on a night work at 1700 hours and see the cavatelli machine sitting out. We all knew that we would be spinning dough for a few hours making pasta. DC Smith would check on us periodically, laughing at us as we were covered in white flour from spinning all the dough. He also was very particular about his red gravy. Who would have known that the man was so Italian with the last name of Smith? The point here is that DC Smith did his best to make the firehouse a family atmosphere. I truly believe to this day that he used the cavatelli as a team-building exercise to enforce the camaraderie of the Philadelphia Fire Department.

As I stated before, he truly wanted everyone to become a better firefighter. I attribute my progression through the ranks to him. As mentioned earlier, the best thing for me was going to Engine 70 at the beginning of my career, because DC Smith continually spoke to me about the importance of learning the job. He always encouraged me to take a promotional test. In our discussions, he told me how he was young as he was promoted through the ranks. He explained to me how he learned at every rank, and if he was to make rank, I would, too. He told me to keep in the books for the promotional tests, and he helped me tremendously with the oral boards. He delivered his message with dignity and respect, which motivated me to want to impress him in an even greater fashion. I continued to study after his retirement and call him with questions. Because of his impression on me, I have only had to take one promotional test for each rank and now currently hold the rank of battalion chief.

With all that being said, the most important moments are the great memories with now a dear friend. DC Smith came to each promotional ceremony from firefighter through battalion chief and our family luncheons afterward. Our families have come together for dinners and parties. DC Jimmy Smith is one of the most influential people in my life, and I am honored to call him my friend.

Thank you for everything, Chief,

Matt Wnek, Battalion Chief, Philadelphia Fire Department

Dad spent decades attending and teaching at the NFA. He made some great friendships and learned an awful lot along the way. One of his friendships was with Dr. Denis Onieal. Dr. Onieal was the chief of Jersey City, NJ, a tough blue-collar city like Philadelphia. Dr. Onieal went on to lead the fire service as superintendent at the National Fire Academy and then as the deputy of the Unites Stated Fire Administration. I contacted Dr. Onieal about this article, and he wanted to pass this along about Dad:

We all receive newspapers and magazines, and inevitably when they arrive, we begin by turning to a favorite page or column. In the case of Firehouse Magazine, my turn-to page is Chief Jim Smith’s column.

As a fire officer, I appreciated the narrative, the insights and the detail. Reading Chief Smith’s column is as if you were in the room with him as he took the time to explain the important points of firefighting strategy and tactics. Although there are several very good authors in the strategy and tactics field, few have been as consistently good over this long period of time. That consistency requires a special breed, years of street experience, and a remarkable talent for identifying the changing nuances of building construction and modern products of combustion that challenge urban firefighters. Without flowery words or complicated descriptions, Chief Smith laid it all out for those of us who were willing to take advantage of his knowledge and experience, and as an urban career fire officer, did I ever!

But for me, the biggest thrill was when he taught command and control courses at the National Fire Academy. Now, all of the NFA instructors are good, but even among the good there are a few rock stars, and Chief Smith was one of those rock stars. During classroom visits when I was superintendent, he and I would engage in discussions about urban firefighting—the strategies and tactics, the funny and the sad, the wins and the losses. Was there competition and comparison between Philadelphia and my beloved Jersey City? You bet there was! Perhaps our sole area of agreement was that both of our departments were way better than FDNY—unless, of course, the other instructor was from the FDNY, then the three of us picked on someone else.

When the history of the 20th and 21st century of firefighting in America is finally written, when the names of the influential are inscribed, Chief James Smith of the Philadelphia Fire Department will be a chapter unto itself.

Dr. Denis Onieal, Deputy United States Fire Administrator (ret.), and Chief, Jersey City, NJ, Fire Department (ret.)

One of dad’s great friends and peers from the PFD is retired Deputy Chief Bill Shouldis. If you haven’t experienced these two as your instructor, you haven’t lived yet. This fast-talking, Philly-slang-spewing duo leave many Midwesterners and southern folk scratching their heads and laughing all at the same time. However, their knowledge of the fire service and ability to relay the information to the students is second to none.

Thank you to Firehouse Magazine for publishing valuable articles that are written by experienced authors. Jim Smith's thoughts on strategic and safety steps has prepared countless fire officers for managing complex command challenges. I have used his practical tips in many situations as an emergency responder and educator.

Bill Shouldis, Philadelphia Fire Department (ret.) & National Fire Academy

While assigned as the director of the PFD fire academy, Dad worked with John McGrath. John was an up-and-comer within the PFD. John was part of the first Executive Fire Officer (EFO) class at the NFA. He rose through the ranks and left the PFD holding the rank of deputy commissioner. John secured the position of fire chief with the Raleigh, NC, Fire Department. John is an extremely intelligent man but an even nicer and humble human being. John acted as a mentor to me while I was progressing through my career. In a conversation recently, John shared this quote with me that Dad said to him: “John, NEVER forget, regardless of your rank, that you are a public SERVANT. Treat everyone like you would like your loved one treated.”

One of the icons within the fire service is Chief Billy Goldfeder. He and Dad have crossed paths for decades between conferences, lectures, the NFA and, probably, signings of their own published books. Chief Goldfeder also is the founder of the Firefighterclosecalls.com website, which is an excellent resource for firefighter safety. I’m hoping that someday that Chief Billy will break out of his shyness. Here are his words about Dad:

I guess I am a member of the second group of lucky ones. I say the second group, because the first would be those (professionally) who worked with Chief James (Jim/Jimmy) Smith in the Philadelphia Fire Department. Of course, his family is even more blessed than that, but we are focused right now on fire folks.

I got to know Jim in the late 80s at the NFA when I was going through the EFO program, and was I wowed after about 10 minutes with our lead instructor, Jim Smith.

For those of you who haven't been to the NFA, and especially the EFO program, it can be pretty intimidating initially. Additionally, the instructors, and I mean this with way more than just due respect, can be and are very collegiate. So, as someone who struggled to get past fourth grade, was tossed from one high school and barely got by community college, I was sweating.

But then in walks Jim Smith (and another wonderful man, also a Chief from Philly, Bill Shouldis, but this is about Jim, dammit!), and he starts speaking. And he spoke in a way that any firefighter could understand. He took the complexities and science of major fire command and control and poured into my head (and heart) without any confusion, without feeling like he was talking down to us, and without using too many big words. He was simply one of those teachers who spoke the language that I understand, as he clearly was there with one mission: to make us all better fire officers.

Jim Smith has no airs, no arrogance and no sense of self-importance, although he is arguably one of the most important leaders in the fire service. Between his work at the NFA, his training, his consulting, his leadership at the PFD and his decades long column here in Firehouse Magazine, he has and continues to make a measurable difference to generations of fire officers.

I was fortunate enough to become friends with Jim over the years and had a couple of chances to spend time riding (and listening) with and to him while he was working at the PFD. We even attended a few working fires, which he led like Leonard Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic. Command, control, one focus with beautiful results. Of course, in Jim's case, being from Philly, he probably preferred a Mummers string band! Even over a couple of summers, my family and I were "down the shore" in Ocean City, NJ, where Jim would have a meal with us or just come by with his famous green tea and talk fire.

If you are a younger firefighter or relatively new fire officer, and you haven't read much of Jim's work, take time and go back and read his Firehouse column. His lessons on fireground operations are timeless. It will cost you nothing, and the learning will be priceless. If you want to dig even deeper and learn as much as possible, check out Jim’s highly popular book, "Strategic & Tactical Considerations on the Fireground (Strategy and Tactics) Fourth Edition."

Either way, if you are on this job—volunteer, career or whatever—spending time reading from Jim will, without question, make you a better firefighter, as he has already done for tens of thousands of us, and for that, we are beyond grateful to our Brother, Chief Jim Smith.

Billy Goldfeder, Deputy Fire Chief, Loveland-Symmes,OH, Fire Department and Firehouse Magazine Hall of Fame Inductee

Although this article was a secret undertaking, so Dad didn’t give me the business for writing it, some word did get out, and I received this nice message from Chief Larry McCoskey:

“Chief Smith has been a positive role model for the men and women of the fire service by teaching, informing, training and otherwise being a great example of what a leader should be. There are very, very few individuals who can match the scope of Chief Smith's contributions. It has been an honor to work with him. Job well done, Jim!"

Larry McCoskey, Assistant Chief (ret.), Louisville, KY, Fire Department and NFA Instructor

I really want to thank Pete Matthews and Rich Dzierwa from Firehouse for allowing me to write this tribute to my father. Dad has poured his heart and soul into the fire service and never has he asked for anything in return. Dad always said in his classes and lectures that “If just one person left gaining new knowledge, he would consider it time well spent.” He is a consummate professional.

Dad is retired now, and we both live in Ocean City, NJ, where I am the fire chief. There are many days when I receive a phone call from Dad while he is out on his daily walk (basically, still preplanning the island) regarding a concern with a building or a heads up about a newly constructed home that has lightweight construction.

He always is reading, writing, talking or thinking about the fire service, and it’s nearly impossible to travel without someone either knowing Dad or having attended one of his classes or lectures. It never gets old hearing people praise Dad for not only his knowledge but his wonderful demeanor. To use Dad’s own term, he’s good people!

Read Jim Smith's final "Fire Studies" column here.

James P. Smith, Jr.

James P. Smith Jr. is a 28-year veteran of the Ocean City, NJ, Department of Fire and Rescue Services. He was promoted to the rank of fire chief in 2016 and is a deputy emergency management coordinator since 2014. Smith earned a bachelor’s degree in public safety administration from Neumann University and is a Certified Public Manager through Rutgers University.