Engine Essentials: Extinguishing Knee Wall Fires

Fires that involve knee walls present unique challenges to engine company members. Construction that includes this design element is extremely common in communities, from urban to rural and from legacy to modern. Responding engine company members must be aware of the potential hazards of fires that involve knee walls and adopt safe and effective suppression tactics.

What is a knee wall?

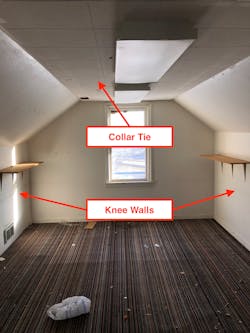

Knee walls are short walls that often are found in the finished half-stories of dwellings. The walls usually range from 3 feet tall to chest height. They typically run the length or width of the building on two parallel sides, although they can be found on all four sides in the case of hip- or mansard-style roofs.

The age of the structure doesn’t matter, because knee walls can be found in rafter- or truss-style roof construction with new room in the attic truss systems.

Knee walls create large void spaces for fire and products of spread laterally. In addition, there usually aren’t fire stops that lead to the rafter or truss space above, which allows smoke and fire to spread overhead. This allows smoke and fire to potentially travel to the other knee wall void that’s on the opposite side of the structure.

In some construction, an overhead collar tie void spans the rafters on opposing sides of the structure. Similarly, room in attic truss systems has a comparable style void.

The presence of a collar tie creates another void space for smoke and fire to spread and build on its way to the other knee wall void.

Fire behavior & hazards

Fire and products of combustion can build and spread unimpeded through the voids. Voids allow access to air through vents and soffits, which creates a volatile smoke mixture in the flammable range. In addition, voids provide ample access to fuel via wood, insulation, tar paper, stored items and other materials.

With interconnected voids, smoke and fire have the opportunity to take hold of a tremendous portion of the structure. Fire can enter the knee walls via two main routes: fire starts inside of the void or outside of the void and extends in. Once fire gets inside of a void, members can find heavy fire or smoke that’s primed for ignition on multiple sides of them. If the fire starts on the floor below them, members can find heavy fire on four sides of them. In the case of hip- or mansard-style roofs, members can find heavy fire on six sides of them.

Extreme fire behavior, such as flashovers, backdrafts and smoke explosions, is a looming hazard when improper tactics are employed. Members often get into trouble when they advance onto the half-story and proceed remote from the stairs. If fire conditions aren’t found in the occupied space, members often begin to open the walls at the farthest point of advancement to look for the fire.

The other common occurrence is the fire is knocked down in the occupied space but heat conditions aren’t improving, and members begin to open the walls and ceiling to look for extension. Frequently, the walls and ceiling are what keep the fire and smoke conditions contained and in a ventilation-limited state. Once the wall or ceiling is opened, extreme fire behavior can result and trap members who operate on the floor.

When extreme fire behavior erupts, it can result in fire conditions that envelop the entire floor because of the large volume of the voids. In the case of a backdraft or smoke explosion, the concussive force can cause walls and ceilings to collapse, which can cause further voids to open and add to the fire conditions. In addition, collapsing materials can injure and trap members on the floor.

With the layout of these dwellings, typically, egress from the half-story is limited. The stairwell often is steep and narrow. Commonly, there is a 180-degree turn at the top of the stairs that’s difficult to navigate during normal conditions, let alone when a hasty retreat is necessary. Windows on the half-story typically are sparse and small, which makes it difficult for a member who is in full turnout gear and SCBA to escape through them.

Size-up

On arrival at a dwelling that has a half-story, it’s critical that members recognize the potential for knee walls and their accompanying hazards. During the initial radio report, it’s important to communicate the presence of a half-story (e.g., 1½- or 2½-story dwelling). This lets responding companies know the potential hazards that they face and ensures appropriate tactics are adopted.

Although knee walls can be found in unfinished attic spaces, the largest hazards occur in occupied or finished half-stories. Several exterior observations can suggest an occupied half-story. Signs to look for include window dressings, window air conditioning units, multiple entry doors that indicate the potential of a duplex and exterior stairs that lead to the half-story. Although these signs don’t guarantee the presence of knee walls, they imply a strong likelihood of a finished half-story.

Members should look for signs that suggest that smoke or fire conditions involve knee wall or collar tie void spaces. Signs include smoke from the soffits and/or gable vents, exterior fire conditions that extend to the soffits, melted snow or tar in the area where there could be knee wall or collar tie voids, discoloring low on the gable ends and fire that appears to be in the occupiable area of the half-story. Members also must be aware of fire conditions on a lower floor that can enter voids via pipe chases or because of balloon-frame construction.

Fire attack

A methodical and coordinated attack is vital to ensure a safe and efficient operation. Multiple hoselines might be required to obtain extinguishment and to protect the egress of operating members. Vertical ventilation might be necessary to reduce the risk of an extreme fire event from occurring.

When making entry into the structure, members should begin their interior size-up. The walls that lead to the knee wall voids and the ceiling that’s below the knee wall voids should be checked with a thermal imaging camera (TIC). If significant hot spots are visualized on the TIC, the walls and/or ceiling should be opened to reduce the chances of fire being below crews who operate on the half-story. In addition, if there are any concerns that the fire might be located in the basement of a balloon-frame structure, a hoseline should be assigned to investigate.

The engine company must advance slowly and systematically onto the half-story. If there’s visible fire in the occupied space, it should be knocked down from the top of the stairs using the reach of the stream. Prior to advancing onto the floor, the knee wall and collar tie voids should be checked for fire or heavy smoke conditions. This ensures that members remain close to the stairs and their point of egress if conditions rapidly change.

The goal should be to make small inspection holes to keep the fire or the smoke that’s primed for ignition vent-limited or, at least, contained behind the wall/ceiling. Using a chisel or the butt end of a hook works well for making small openings while maintaining the integrity of the wall/ceiling. Once an inspection hole is made, it should be examined with a hand light or a TIC to check for fire or pushing smoke conditions. It’s critical that inspection holes be made in all voids, because conditions might differ in each space.

If heavy fire or smoke pushing from the inspection hole is observed, vertical ventilation is required to reduce the risk of an extreme fire event. The engine company should maintain a position that’s close to the stairwell until vertical ventilation is achieved. If necessary, an inspection hole can be expanded slightly to allow a nozzle to flow into the void. A bent-tip nozzle works extremely well for this, because it easily fits into an inspection hole and can be rotated to cover the entire void and often the interconnected rafters/trusses.

Alternative means of attack must be considered when conditions don’t permit members to operate on the half-story or low staffing doesn’t allow for vertical ventilation. If these situations arise, members should drop down to the floor that’s below the half-story and begin to open the ceilings under the knee wall voids. Hoselines should be positioned to facilitate fire extinguishment in each void. Once conditions improve, members should reengage on the half-story.

Overhaul

Once the fire is knocked down, extensive overhaul is required. All void spaces should be examined and/or opened to ensure that no extension occurred through the interconnected voids. The floors below the half-story should be inspected to verify that there’s no drop down of burning material from the half-story.

About the Author

Jonathan Hall

Jonathan Hall, who is a Firehouse contributing editor, has more than 24 years of fire service experience. He currently is a captain with the St. Paul, MN, Fire Department assigned to Engine Company 14. Hall also serves as a lead instructor in the department's Training Division; he teaches hands-on skills to members of all ranks. Hall is the co-owner of Make The Move Training LLC and teaches engine company operations throughout the country.