Making the Emergency Scene Work—Part 1: What Company Officers Should Expect From Their Chiefs

Editor's Note: This is Part 1 of a two-part series from Dennis Reilly. Part 2 will follow next week and will be found here.

Any emergency operation, be it fire, rescue, hazmat, mass casualty, etc., requires an effectively functioning team. Everyone must know their job, and supervisors must support the efforts of the whole team. Operations always are the sum of the parts: The engine company doesn’t put out the fire; the fire department does.

Most successful operations are conducted by departments that are constructed in a way in which everyone understands everyone else’s role. When we understand, we can support. It’s just that simple.

Company officer needs

There are two reasons to start at the company level. First, a chief won’t get respect if that person doesn’t give respect. A chief’s attitude, whatever it might be, comes across very clearly, so those who the chief leads must be positioned to conduct good operations.

Second, the company level is where the rubber meets the road. You can be the best strategic mind in the world, but if companies don’t work well, plans won’t be accomplished.

Now that I have more than 30 years in the chief officer ranks, I really have an appreciation for how important the company officer is.

The station house

Consistency is the key, and that’s what company officers need in their chief. We all worked for chiefs who change their personality and behavior with the wind. At shift change, you hear, “Boy, I wonder which Chief Smith will show up today.”

Chiefs must understand and respect the fact that what they do in the station lays the ground work for the street. Company officers must believe that their chief will be a calming force when the world is going sideways. A chief of many personalities will fail in this regard.

Furthermore, honesty means everything. As a company officer, I had a chief who always told us, “You guys did a great job.” Well, sometimes we didn’t. We knew that we screwed up, and we wanted to talk about it. We wanted to learn from it. We wanted to make sure that it never happened again.

Men and women who are willing to risk their life to serve their community have earned the right to hear the truth. If chiefs won’t face the truth and have the courage to tell the truth, the people who are under their command will see right through this. Yes, chiefs must be diplomatic when dealing with sensitive items, but they always must be honest in their remarks. In my mind, once chiefs lose their credibility, they lose the privilege to lead.

When I knew that my chief really cared about my safety, I was more likely to push that extra little bit. The chief was a good risk manager and looked out for us while allowing us to do our jobs. Everyone who was in my company knew that someone had their back. We wanted to make sure that our chief knew that meant a lot to us.

Caring for the members’ safety isn’t always easy. Sometimes, chiefs must be the “bunker cop.” Sometimes, they must say no. No doubt about it, having and communicating a clear concern for the safety of members energizes a chief’s force. As fundamental as this might sound, there are a lot of chiefs who don’t send this message clearly.

Realistic assignments

When chiefs deploy forces at a scene, those forces must have a clear idea of the big picture.

For many decades, many companies were expected to basically operate in a vacuum. They arrived on the fireground, they were given a task, and they went about their business. Chiefs often overlooked how important it is for everyone who’s operating to understand the overall perspective.

I am very impressed with agencies that have their first-arriving officers announce their initial report and their mode of attack or strategy. The simple articulation, for example, that an attack will be offensive helps a lot. When companies are clear on what the incident commander (IC) is trying to do, the possibility for freelancing decreases.

Furthermore, when the strategy is known by all of the players, company officers have a frame of reference by which to judge members’ performance.

If I am simply told to advance a hoseline to Division 1 and to keep the bathroom from catching fire, that’s what I will do. The entire house might burn down around me, but you can bet that I will protect that bathroom.

If I am told to advance a handline to the bathroom on Division 1 to cut off fire spread to the upper floors, I know exactly what the IC is trying to do.

Many of you might believe that this is kind of silly, and I respect everyone’s opinions. I will say that when you work at the task level, it’s very easy to get immersed in your task. The explanation of how your task fits into the big picture will, in the long run, make you more efficient, allow you to manage the risk and contribute to overall mission success.

My experience tells me that the vast majority of company officers always try to complete the assignments that they are given. What they really need is to be given realistic assignments.

I am the first one to admit that after riding in the chief’s buggy, I have lost a feel for how difficult it is to advance a charged 2½-inch handline to Division 2 with a three-member engine company. Company officers need chiefs who give them a realistic task and the resources that are needed to accomplish the task.

It’s very easy in the heat of battle for a chief to make assignments and move on. However, let’s work this one out a step further. How likely is it for a new lieutenant to tell a battalion chief, “We can’t get that done, chief”? Say what you want, but I don’t know many new officers who would make that statement. Even worse, I know a lot of departments where making that statement could be the death blow to a career.

A good chief always assigns tasks that are realistic. If the assignment is beyond the capabilities of a company to accomplish, the chief either must rethink the assignment or provide the adequate resources. Many will say that the company officer is the one who should decide whether the company can complete a task. I say the good chief knows this before the order is ever given.

Operational updates

Emergency scene operations can be very demanding. As such, it’s important for chief officers to give their company officers the room and time to work. Too often, a company, a division or a group is given an assignment, and the IC asks for updates every minute. Yes, some tasks are very time sensitive, and an IC must stay on top of the situation. On the other hand, a company’s stretch of a line up the interior stairs to Division 4 won’t happen in two minutes.

There isn’t anything more frustrating for company officers than for them to have to drop what they’re doing to give a radio report that really doesn’t have any bearing on the incident. I teach my officers that, unless they have something significant to report in terms of the ICAN (identification, conditions, actions, needs) model, they should try to stay off of the radio. In return, I will leave them alone unless I see something from the outside that gives me concern for their safety or the effectiveness of operations. Yes, chiefs, this takes a lot of discipline, but if you adopt this model, your tactical operations will be enhanced greatly.

Support & strength

This article was written for chief officers in the hope that the information will help them to support their subordinate officers at emergency scenes. As we strengthen the relationship between the parts, operations become more efficient. Remember, ours is a team sport, and we must work to ensure that all of the parts fit together well.

About the Author

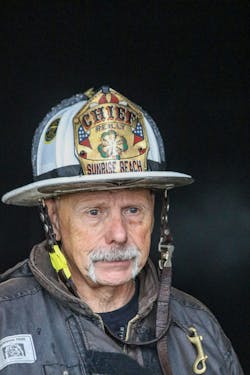

Dennis Reilly

Dennis Reilly is a 48-year fire service veteran and retired fire chief and is the owner of The First Line Fire Service Training Company. Reilly served as the fire chief in Pittsburg, KS, and Sunrise Beach, MO, and as an assistant in North Carolina and California and retired as a battalion chief in Cherry Hill, NJ. He was an original member of New Jersey Urban Search and Rescue Task Force 1. Reilly holds a master’s degree in public administration from Penn State University and is a CFO. He has spoken at numerous events, including the Command Officer Boot Camp and the Orlando Fire Conference. Reilly is a U.S. Army veteran who served in Iraq during the Operation Desert Storm.