Let’s get into the research

Survivability is a complex concept and things such as age, gender and physical fitness all play a role in what level of hazard the human body can withstand. This makes it even more difficult for initial arriving companies to size up the structure and make an assessment as to where the survivable spaces are located. Fire research can aid in this assessment. The environment inside a furnished single-story ranch structure was measured during 25 fire experiments as part of the “Impact of Fire Attack Utilizing Interior and Exterior Streams on Firefighter Safety and Occupant Survival: Full Scale Experiments.”1 Measurements of gas concentration, heat flux and temperature were used to approximate the hazards to potentially trapped occupants prior to the fire service arriving between five and a half and seven minutes.

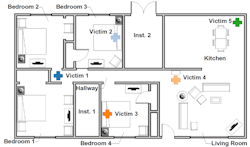

A package of instruments for each simulated victim location was installed throughout the house labeled as shown in Figure 1. The location labeled Victim 1 was located immediately outside the fire compartment. Victim 2 was behind a closed door. Victim 3 was on the bed in an open room down the hall from the fire room. Victim 4 was on the floor in the living room and Victim 5 was in the most remote part of the structure from the fire room.

An occupant inside the compartment of origin would not have survived to the point of fire department intervention in any of the experiments. All of the experiments had the potential for flashover prior to fire department intervention. Occupants just outside the compartment of origin (hallway of the bedroom fire) were exposed to levels which exceeded the survivability threshold based on thermal exposure. Figure 2 illustrates the thermal exposure calculated in the form of fractional effective dose (FED) where a value of 1.0 represents a fatal dose for 50 percent of the population also known as the LD50.2 The LD50 for temperature is based on statistical data from burn injuries. FED is the percentage of the LD50 the occupant was exposed to. A FED of 0.1 is equivalent to 10 percent of the LD50 and .9 is equivalent to 90 percent of the LD50.

Victim 1, who was closest to the fire, received the highest dose whereas Victim 5 was farther from the origin and received the lowest dose (see Figure 1). In general, the higher the FED, the less chance of survival.When assessing the hazard from toxic gas exposure, the higher up the space elevation, the more hazardous the atmosphere. Figure 3 illustrates the exposure from the smoke. Victim 3 was located on the bed in the bedroom down the hall from the fire room, yet because of the elevation in all three ventilation cases, received the largest dose. Similar to the thermal dose, a lethal dose would be a FED of 3.0 representing a LD50.

Figure 4 identifies the likely not survivable areas in red, the hazardous but potentially survivable areas in yellow and the likely survivable areas in green when it comes to a bedroom with one window venting fire.

The scientific data tying survivability to the proximity to the fire and the elevation in the space can be used during size-up and the ongoing assessment of risk versus reward.

Where survivable spaces exist, additional risk may be warranted when conducting suppression and search and rescue operations. Assessing the location of the fire, area of involvement of the structure and flow paths help identify the survivable spaces in a structure fire. Keep in mind, occupants trapped in a structure fire have a limited amount of time before they are exposed to a potentially fatal dose of toxic gases or total heat flux. The amount of time is often very short when compared to the response times of fire departments. Immediate intervention involving suppression and subsequent coordinated ventilation is necessary to increase the survivability of all spaces in the structure.

References

1. Zevotek, R., Stakes, K. and Willi, J. “Impact of Fire Attack Utilizing Interior and Exterior Streams on Firefighter Safety and Occupant Survival: Full Scale Experiments.” Underwriters Laboratories Fire Fighter Safety Research Institute. January 2018.

2. Purser, D. “SFPE Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering.” 2002. 2-83

Read the final report at ulfirefightersafety.org/docs/DHS2013_Part_III_Full_Scale.pdf

For more information on the project, visit ulfirefightersafety.org/research-projects/impact-of-fire-attack-on-firefighter-safety-and-occupant-survival.html

Robin Zevotek

Robin Zevotek is a research engineer with the Underwriters Laboratories (UL) Firefighter Safety Research Institute and a captain with the Ellicott City Volunteer Fire Department in Howard County, MD. He holds a master’s degree in fire protection engineering from the University of Maryland and is a licensed professional engineer (PE).