The Rapid Intervention Reality of Your Department - Part 1

The sound of "Mayday, Mayday" heard over the radio on the fireground will bring a sense of uneasiness and urgency to every fireground commander, no matter what the commander's level of experience or expertise. One of our own is in trouble. Are we prepared at all levels of our organization to bring that member home safely? (Figure 1.)

Let's begin by reflecting on why we need rapid intervention teams (RITs). Sadly, there are many misnomers when it comes to the true answer to this question. But let's begin with the obvious.

As a fire service, we are bound by various regulations and standards, one of the most relevant being the Respiratory Protection Standard developed by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), which was revised in 1998 to include a provision known as the "two-in/two-out" rule. Basically, the rule states that if personnel are to enter a hazardous atmosphere, at least two individuals are to remain outside the atmosphere while maintaining visual or voice contact. One of the two individuals must not be assigned any additional duties that would be vital to the safety of the firefighters in the immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH) environment and the other individual may be assigned to other firefighting activities as long as they do not interfere with that person's ability to perform an immediate rescue if needed. An example of the latter would be a pump operator.

In 2001, the National Fire Protection Association published its NFPA 1710, Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Career Fire Departments, and NFPA 1720, Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations and Special Operations to the Public by Volunteer Fire Departments. In these standards, the term "Initial Rapid Intervention Crew (IRIC)" was referenced. This was a valiant attempt at getting the rapid intervention concept recognized and implemented on the fireground. Unfortunately, these standards did not address the skills and performance requirements needed by the individuals filling this role on the fireground.

RIT Standard

In 2006, a committee began working on setting a standard for the basic skills and performance requirements for training firefighters in rapid intervention. The result of this is NFPA 1407, Standard for Training Fire Service Rapid Intervention Crews, which was put into place on Dec. 5, 2009. NFPA 1407 is essentially a compilation of numerous other standards as they apply to rapid intervention. Professional standards for firefighters, fire officers, training reporting, respiratory protection, occupational health and safety, incident management, rope rescue, self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) and deployment of resources are all referenced as major portions of the standard. The most important point about this standard is that it was truly designed with firefighter safety being the main issue in all aspects.

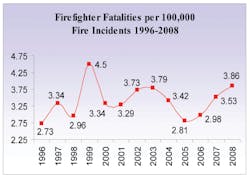

Getting away from all of the textbook answers to our question, though, is the number-one reason why we need rapid intervention on the fireground: because we continue to lose, on average, more than 100 firefighters each year in the line of duty. The amount of working fire incidents has decreased by 66% over the last 33 years, but our line-of-duty death numbers remain roughly the same. Looking at firefighter fatalities per 100,000 working incidents provides us a clear picture of where we stand. (Figure 2.)

Fallacies and Roadblocks

It is important, however, that we as a fire service realize that rapid intervention is not the ultimate answer to ensuring our survival on the fireground. We have to take care of ourselves and stay out of situations that will warrant activation of the RIT function. Our job as firefighters will always be dangerous because there are times that we must take calculated risks and sometimes we have no control over what happens. But the more that we know and understand about our job and the mistakes that we consistently make as a fire service can and will make a difference.

The five most common factors cited in National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) firefighter fatality reports are all things that we can control before we even hit the street to respond to an alarm:

- Breakdowns in the Incident Management System

- Lack of, or inadequate, standard operating procedures (SOPs)

- A breakdown in the accountability of personnel on the fireground

- Breakdowns in communications on the fireground

- Lack of recognition of key aspects related to fire behavior and building construction (Figure 3)

These are areas that we must constantly look at and evaluate ourselves on, no matter what position we fill in our organization.

RIT Studies Cited

The notion that one RIT is adequate to execute a rescue is a fallacy. This fallacy is clearly illustrated by studies conducted by the Phoenix, AZ, Fire Department after the loss of Firefighter Brett Tarver in a supermarket fire in 2001. The studies, conducted by the fire department and Dr. Ronald Perry of Arizona State University, demonstrated several items that must be clearly understood in the realm of rapid intervention:

- One in every five rescuers needed to call their own Mayday

- It took an average of eight to nine minutes for a RIT to reach a downed firefighter

- It took an average of 22 minutes to find, package and secure an alternate air supply

- It took an average of 12 firefighters to rescue one downed firefighter

These results were obtained in conditions not containing high heat and smoke that would be encountered on the real fireground. If these results are not believable to a reader, I would challenge them to keep times and data from their own RIT training exercises and compare them to this data. They will undoubtedly be very similar.

The RIT function on the fireground is often behind the eight-ball before it is ever established because the concept is not used properly. It is sad to say that a lot of chief officers do not have a good understanding of the RIT concept. Statements have actually been made by chief officers stating that they do not put a RIT in place on the fireground because they do not want citizens or political figures asking them why a building is burning down and firefighters are standing around watching.

Statements such as this stem from a misunderstanding of the concept. Chief officers need to be involved with their department's RIT training. They do not need to be involved in intensive hands-on exercises, but they should have an understanding of the function if they are going to manage it. Witnessing the members completing the various exercises as well as practicing in the role of the incident commander managing a training Mayday can and will go a long way.

Another issue is that most firefighters do not like getting assigned to the RIT function because they feel that they are not "part of the action." Let's face it, most of us got into this profession because we want to make a difference, but not assigning a RIT for this reason is invalid. Standing next to the incident commander across the street waiting for the order to "go" or down the block in staging is not effective rapid intervention.

Firefighters making up the rapid intervention function on the fireground have to be allowed the freedom to provide additional safety factors that may be overlooked. It is important that this is done in a manner that does not take the team away from being readily available to be placed into action in the need of a rescue.

Firefighters assigned to the RIT must remain vigilant and focused at all times — their efforts may mean the difference between life and death for a firefighter in trouble. Complacency is very easy to set in if the RIT is not allowed to function in the proper manner.

Deployment Models

Many different deployment models for the RIT are available. The most important thing that can be stressed is that the model used must fit and be conducive to your department. Just because a big-city department uses a particular deployment model does not mean that it will work for every department. Once assigned to the RIT function, a company should not be reassigned to provide relief for units involved in suppression. NFPA 1407 specifically mentions this in the sample operating guideline contained in it. Large gaps in the safety of our members take place when this happens. Continuity of rescue plans of action, monitoring of conditions as well as tools, equipment and resources all become issues when this is done.

No matter what deployment model is used, it cannot be argued what the goals of the first RIT deployed should be. The most important action is to locate and get air to the downed firefighter. Air supply is the one resource we must make certain we maintain to ensure the downed firefighter's chances of survival. If an environment can be maintained tenable and we have air to the down firefighter, it can possibly buy us the time that is needed for extraction.

To this point, we have talked about a lot of the preliminary items that must be understood to have a successful RIT on the fireground. The most powerful item, however, is the attitude we take when it comes to rapid intervention. It truly is the crayon that colors our world. Firefighting is serious business that requires serious people.

If we approach rapid intervention with the attitude that it is important and have fire department members genuinely interested in filling the role in the proper manner on the fireground, we have overcome the first obstacle. The remaining parts of this series will focus on preparation, assessment and training.

JEFFREY PINDELSKI is the deputy chief of operations for the Downers Grove, IL, Fire Department and western regional director for the Fire Department Safety Officers Association (FDSOA). He is the author of the text R.I.C.O.- Rapid Intervention Company Operations, a revising author of the third edition of the Firefighter's Handbook and a Firehouse.com contributing editor.

About the Author

Jeffrey Pindelski

JEFFREY PINDELSKI is the Downers Grove, IL, Fire Department Chief (Ret.) and has been a student of the fire service for more than 30 years. He served as a chief officer for more than 15 years of his career, during which time he directly managed every aspect of the fire department at one time or another. Pindelski holds a master's degree in Public Safety Administration from Lewis University and earned a Graduate Certificate in Managerial Leadership and a bachelor's degree from Western Illinois University. He is the co-author of "R.I.C.O.- Rapid Intervention Company Operations" and was a revising author of the third edition of "Firefighter's Handbook." Pindelski presented at numerous fire service conferences and had more than 55 articles published in trade journals on various fire service-related topics. He is a recipient of Illinois' Firefighting Medal of Valor.