Close Calls: Firefighters Trapped At Maryland House Fire - Part 2

As reported in part one of this column in the July issue, on Feb. 24, 2012, the Prince George’s County, MD, Fire/Emergency Medical Services Department (PGFD) responded to an arson fire in a single-family dwelling at which seven firefighters were injured. Given the severity of the injuries and the magnitude of the event, an investigative team was ordered by Fire Chief Marc S. Bashoor, in accordance with the department’s General Order 08-18: Safety Investigation Team (SIT). This series of columns provides an overview of the fire and the process used to determine what went wrong – and how those issues can be avoided in the future.

Additionally, the Prince George’s County Fire/EMS Office of the Fire Marshal conducted its investigation to determine the origin and cause of the fire. Assisted by members of the Prince George’s County Police Department and special agents from the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), the Fire Marshal’s Office determined the fire was incendiary in nature. At the time of this writing, this case remains as an open active criminal investigation.

Fire behavior prior to the fire department’s arrival:

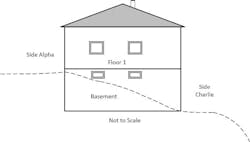

The fire originated in the basement of the condemned structure. Prior to the arrival of the fire department, the fire had enough fuel (minimal contents), oxygen, heat and time to grow to a size sufficient to have smoke and flames exiting at least two windows in the basement on sides Bravo and Charlie.

Flames extending out of the windows and observations of smoke throughout the rest of the structure indicate that the fire had reached a ventilation-limited state. These two windows were in the Bravo quadrant of the basement and included a small window in the bathroom on side Bravo and a larger window in the kitchenette on side Charlie. These windows, aided by the wind, provided an inflow of air that supplied oxygen to the fire and supported rapid fire growth in the basement.

The exterior basement door initially was intact and closed. The status of the basement windows outside of the Bravo quadrant is not known. However, the scene examination indicated that they were intact and closed at the start of the fire. All of the windows and the door on the first floor were closed. Therefore, the two windows in the Bravo quadrant of the basement provided the only means of ventilation during the initial development of the fire. Based on the size and location of the windows, the wind, and observations, it is likely that the majority of the inflow was provided by the larger window on side Charlie and the smaller window on side Bravo was mostly an outflow.

The interior door to the basement steps was open, which let the smoke and hot gases produced by the fire fill both the basement level and first floor. Smoke was initially observed pushing from the eaves on the first floor. At this point, the first floor was filled with smoke and was at a positive pressure (above neutral plane) due to the fire-induced, buoyancy-driven flows and the wind conditions. Even though the interior door to the basement steps was open, this lack of available oxygen and positive pressure prevented the spread of fire to the first floor and kept the fire’s flow path in the basement level. The flow path of the fire was effectively contained in the Bravo quadrant of the basement.

Fire behavior after the fire department’s arrival:

Approximately 6.5 minutes after the initial 911 call, firefighters forced the door on the first floor, side Alpha, of the structure. In the fire service, the term “ventilation” has been defined as the systematic removal of the products created by a fire (i.e., smoke, hot gases) and replacing them with cooler, fresh air to facilitate firefighting operations. Historically, forcing the front door of the structure to make entry may not have been thought of as “ventilation” by many firefighters. However, whenever an opening is created, ventilation has occurred.

The action of opening the front door immediately changed the fire’s flow path and dynamics by adding an opening above the neutral plane. Thick, dark, black smoke pushed out of the front door, filling the front yard with smoke. The open front door added an outflow on the first floor that let the fire in the basement grow and increase in size and directed much of the hot smoke and gases up the interior stairwell and out the front door. This situation, which occurred due to the natural fire-induced flows, was only intensified by the high winds impacting side Charlie of the structure. The outflow path of hot smoke was in the same area where Truck 809 Forcible Entry and Truck 809 Officer began their search. These firefighters reported seeing only smoke initially, but eventually flames beginning to come up the interior basement stairs.

Approximately 1.5 minutes after forcing the front door, firefighters on the first floor noticed a sudden change in the airflows that caused the front door to slam shut. Once the front door was shut, the flow path of the fire once again changed. The hot smoke that was coming up the interior stairwell and escaping out of the front door was now trapped on the first floor. This dropped the smoke layer to the floor and temporarily increased the temperatures from floor to ceiling in the front room.

Approximately 30 seconds after the front door shut, windows were broken on the first floor for firefighter self-rescue and exterior ventilation operations. Prior to firefighters reopening the front door on side Alpha to initiate a rescue of Truck 809 Forcible Entry, Engine 809 firefighters on side Charlie entered the basement and put water on the fire. While the rescue was being completed, these firefighters extinguished the majority of the fire, improving conditions throughout. Once rescues were completed, the structure was evacuated by command and firefighters re-grouped prior to completely extinguishing the fire.

Fire behavior conclusions:

1. Initial observations indicated that on arrival of the fire department, there was a ventilation-limited basement fire that was aided by high winds from the northwest. These observations included:

a. Flames out two basement windows.

b. Pressurized smoke condition on the first floor.

c. Significant and unusual smoke conditions in the front yard.

d. High winds impacting side Charlie of the structure.

2. When the front door was opened on the first floor, the fire flow path changed and the size of the fire increased. The additional ventilation, without the application of water to the fire, made conditions within the structure worse (i.e., higher temperatures and larger fire size) and drove much of the hot smoke up the interior stairs and out the front door.

3. While the change in flow path occurred due to the natural fire-induced buoyant forces, the wind conditions only added to this by driving hot smoke and gases up the interior stairs and out the front door. This further increased the size and intensity of the fire, and more rapidly changed the flow path.

4. Truck 809 Officer and Truck 809 Forcible Entry were in the outflow path and exposed to high-velocity and high-temperature gases, adding significant convective heat transfer, which ultimately resulted in serious burn injuries.

The results of the operational safety investigation:

The following is a brief overview of the critical points related to this fire. The actual report, which is available at www.PgfdFireReport.com, is organized into two parts. Part one provides a detailed description of the facts pertaining to and leading up to the emergency situation that injured the firefighters. Part two is an analysis of the incident, which describes the factors that led to the outcome, as well as the recommendations.

• Command and control of incident operations. This is a primary responsibility of unit and command officers. Command presence and control of the dynamic situations associated with structure fires is a critical element to safely mitigate an incident. This incident demonstrated the need to establish one standardized county-wide system of command documentation, control and management during operations. A standardized fireground tactical command board, sheet and system needs to be established and distributed to all chief officers within the PGFD. This county-wide tactical command sheet/board must be required for use in any multi-unit response to ensure command and control of incident operations.

• Fireground safety and accountability. These are critical to safe fireground operations. Crew integrity and accountability during incident operations must be maintained at all times to ensure the safety of the personnel. It is imperative that the department adopt a culture of personal safety by the members and embrace fireground operational safety practices as a part of incident operations.

A life-threatening firefighter emergency occurred during the initial company operations, but a firefighter Mayday was not transmitted effectively at this fire. Company officers and firefighters need to recognize life-threatening events and transmit Maydays immediately. There are numerous recommendations that address improvements to fireground operations, firefighter safety, accountability and lessons learned from this incident.

• Personal protective equipment (PPE). A firefighter’s PPE is often the last line of defense against injury in critical situations, such as entrapment. It is imperative that the department foster a culture that ensures all personnel wear only department-approved, National Fire Protection Association (NFPA)-compliant PPE. An evaluation of the PPE worn by the injured firefighters at this incident revealed that several of them, including those most seriously injured, were wearing non-approved PPE items. Regular inspections are recommended to ensure compliance with all policies related to PPE, including the 10-year expiration contained in current NFPA standards.

• Strategy and tactical operations. These are the basic foundations of effective and safe incident operations. The present fire environment, as well as occupant and firefighter survivability, are all key factors in strategic and tactical decision-making at structure fires. This incident involved critical strategic and tactical decisions by the initial-arriving unit and command officers. Many training recommendations in the report identify the need to develop and deliver a standardized strategy and tactics training program for all ranks.

• Environmental conditions and wind-driven fires. Environmental conditions, such as wind, are significant factors that can dramatically impact fire development and spread. Personnel operating at this incident experienced significant sustained winds and gusts that impacted fire development and spread. Firefighter training curricula must incorporate the impact that environmental conditions have on fire development and spread at structure fires.

• Fireground communications. Effective fireground communications during fireground operations are important elements of incident command, firefighter safety and accountability. Structure fires are complex incidents that require effective communications to ensure the continuity of operations by the personnel and incident command. There were numerous portable radio transmission issues during this incident. There were significant challenges associated with radio communications during the incident. The report identifies the lessons learned and provides recommendations.

• Risk assessment and decision-making at structure fires. Initial-arriving company officers at structure fires “make or break” the incident operations by their initial decisions. The initial implementation of the strategic and tactical operations are set by the first-arriving company officers. Scene size-up, building construction, environmental conditions, fire development and spread as well as occupant and firefighter survivability are all important components of risk assessment and decision making for unit and incident command officers. This incident involved critical decision-making by the first-arriving unit and command officers. The report addresses the challenges the officers faced at the fire.

• Command and company officer training. Training is the foundation of safe fundamental fireground operations. A comprehensive basic training program for command and company officers is an important component to be successful at structure fires. This incident illustrates the need for a department-wide, comprehensive basic training program that focuses on the fundamentals of fireground operations. Compliance with all policies and procedures is critical to ensure personnel operate safely during routine and emergency situations. The crews operating at this incident did not follow all existing policies and procedures.

• Fire behavior and size-up. Size-up by company and command officers is an initial critical task that must be conducted by first-arriving officers. Completing an initial size-up by first-arriving officers provides intelligence for them to develop strategic and tactical decisions at structure fires. This fire demonstrates the critical need to ensure a complete 360-degree size-up of fire conditions, building construction, environmental conditions and life safety. A thorough understanding of fire behavior, including fire flow paths and the impact of ventilation and weather conditions, provides essential knowledge to effectively establish an appropriate incident action plan.

• EMS triage, treatment and transport. Response to structure fires requires the response of EMS units, which provide the necessary resources to triage, treat and transport occupant victims or injured firefighters. EMS units need to assemble the necessary equipment and stand by in a location on the fireground that enables the providers to access any victims or injured firefighters. This incident illustrated the need to have EMS resources respond to all structure fires. There were multiple firefighter injuries that required the use of EMS personnel and units available to triage, treat and transport the firefighters.

Next: Recommendations resulting from the safety and operational investigation report

Related:

- Close Calls: Firefighters Trapped At Maryland House Fire - Part 1

- Close Calls: Firefighters Trapped At Maryland House Fire - Part 3

A complete copy of the PGFD Safety Investigation Report for this fire is available at www.PgfdFireReport.com.

About the Author

Billy Goldfeder

BILLY GOLDFEDER, EFO, who is a Firehouse contributing editor, has been a firefighter since 1973 and a chief officer since 1982. He is deputy fire chief of the Loveland-Symmes Fire Department in Ohio, which is an ISO Class 1, CPSE and CAAS-accredited department. Goldfeder has served on numerous NFPA and International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) committees. He is on the board of directors of the IAFC Safety, Health and Survival Section and the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation.