Reducing Firefighter Injuries & Preventing Fatalities

Firefighters take too much risk for too little benefit. For example, firefighters were recently killed in two separate incidents, one involving the collapse of a residential building over 24 hours into the fire while attempting to extinguish hot spots and another while attacking a fire in the basement of an unoccupied building. These losses of life occurred during efforts to save property.

These line-of-duty deaths (LODDs) are tragic because they could have been prevented. While it is right and fitting to honor the sacrifice these firefighters made, it is also time to stop the sad and unnecessary loss of life in the fire service. It is time to recognize that efforts to reduce fireground injuries and fatalities have only been marginally effective (we’ve reduced LODDs on the fireground, but there is still work to be done), and that other approaches to the problem must be examined. With this in mind, this article takes a hard look at the problem and offers two approaches that have been proven to reduce injuries and prevent fatalities in high-risk occupations.

Examining the numbers

Why is the high rate of fatalities and injuries tolerated in the U.S. fire service? Some argue that the loss of over 80 lives every year and over 76,000 injuries is just the cost of doing business in a high-risk occupation. However, research into other high-risk occupations and other fire service organizations around the world has demonstrated that the firefighter casualty rates in the U.S. are extremely high. There are many occupations and fire service organizations around the world that operate in high-risk environments and do not suffer such losses.

Others argue that the fire service should adopt a culture of safety instead of a culture of extinguishment. Maybe the focus of this conversation should shift to the fire service adopting a culture of maximum operational effectiveness. Firefighter injuries and fatalities reduce operational effectiveness dramatically. When a firefighter is lost, trapped, injured or feared dead on the fireground, the focus of the operation shifts from saving civilian lives and property to saving the firefighter. When resources, time and effort are drawn away from saving civilian lives and property, operational effectiveness declines. As such, there will inevitably be more civilian casualties and more property loss because there are fewer resources focused on saving civilian lives and property.

Another possibility is that the identity of the fire service as an occupation of brave, courageous and self-sacrificing individuals is so strong that firefighters deny the magnitude of the problem or rationalize what would objectively be considered unacceptable behavior. For example, there have been incidents when a firefighter was killed during what was essentially overhaul operations hours after the initial response. What we typically hear at press conferences about these losses is the fire chief making statements honoring the dead. What we almost never hear is a fire chief stating that this was a tragic and unnecessary loss of life and that we (fire leaders) must do everything we can to prevent this from ever happening again in our department. In other incidents, firefighters have been severely injured falling through the roof of an unoccupied house. There was no purpose served by going to the roof to ventilate a structure that would have been torn down later. But what we typically hear is the fire chief saying that they were following standard operating procedures (SOPs), and that they would do the same thing again.

It is time to recognize that the public does not see this type of behavior as rational or necessary. The public does not expect firefighters to die or be severely injured attempting to save their belongings. If you doubt that, ask your friends or neighbors what household item they would sacrifice their life to save. Inevitably, they will tell you there is absolutely nothing in their home worth their life. If it is not worth their life, it is not worth yours. The motivation for firefighters to take risks comes partly from a desire to uphold the honor and reputation of the fire service through a demonstration of personal courage. But it is a false idea of honor to die trying to save something worth less than your life.

So what is the difference between the U.S. fire service and high-risk occupations and other fire service organizations that have low casualty rates? There are two big differences:

1. They take a very comprehensive approach to managing safety.

2. They train their personnel how to manage risk rather than just take risk.

The result is low rates of injuries and fatalities, higher levels of operational performance, and reduced costs.

Managing safety

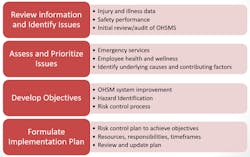

An example of a comprehensive approach to managing safety is the American National Standard for Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems (ANSI/ASSE Z10-2012, Revised 2017). This standard is based on a quality management standard and has been used around the world for decades to effectively manage health and safety. It is a tool that can provide for continual improvement in health and safety performance; reduce the occurrence and cost of occupational fatalities, injuries, and illness; and facilitate improvements in operational performance.

The standard is intended to be flexible enough for any organization to identify appropriate opportunities to improve the way that health and safety are managed. Conducting an initial audit comparing the current health and safety practices against the standard is a good way to start the process of making improvements. Many fire departments already engage in some or many of the practices recommended in the standard, but may not have organized the effort into a systematic approach to identifying hazards and reducing risk. An audit will provide a baseline assessment of where you are and where you want to go with the standard.

Training to manage risk

Because the fire service operates under conditions of uncertainty and risk, it is critical to train personnel how to identify hazards and manage risk. Operational risk management has been practiced in other high-risk occupations for decades with great success in reducing injuries and preventing fatalities. Most fire service organizations in the United States train their firefighters to be aggressive in fireground operations. The only policy statement used to manage risk is typically limited to “risk a lot to save a lot, risk a little to save a little, and risk nothing to save nothing.” Statements such as these do not change attitudes or behaviors. Unless personnel are trained to manage risk, they will continue to take risks. What we have seen over the years, with the lack of improvement in reducing firefighter injury and fatality rates, is that if the same system of operations continues, so will the same consequences—high rates of firefighter injuries and fatalities.

The process of successfully managing risk includes five steps:

- Clarify Benefit

- Identify Risk

- Compare Risk and Benefit

- Decide

- Act

All crews operating on the fireground, or any other emergency incident, must have a clear understanding of what they are trying to save; that is, what benefit they are trying to achieve. They must also know when what they are trying to save changes. For example, in the early stages of an incident, crews may be working to save lives, but after that has been accomplished, or there are no lives to be saved, then they must know that the level of benefit has changed. This is critical because the level of benefit determines the acceptable level of risk. Early on, if efforts are directed at saving lives, then higher levels of risk taking are appropriate. Later, when there are no lives to save, the level of risk taking should be much lower.

Every firefighter must be able to identify the hazards associated with emergency operations. Each crew involved emergency incident operation is typically assigned some type of tactical objective or task. Every tactical objective or task involves certain hazards that could cause harm to firefighters or impede progress toward accomplishing the objective or task. Individual crews must therefore be trained to recognize these hazards and how to either control the hazard or minimize the associated risk.

After benefits are clear and the level of risk involved in tactical operations identified, the next step is to compare risk and benefit. If the level of risk is high but the benefit is low, then something needs to change. Either change the tactical objective, eliminate the hazard or implement controls that minimize the risk. Once the decision has been made about the actions that will be taken and the controls that will be used to reduce to an acceptable level, the last step is to act and make it happen.

It is important to understand that operational risk management is not about eliminating all risk. It is about reducing risk to acceptable levels. It is not possible for anyone to make good risk management decisions without appropriate training and practice. Sayings on the wall will not change 200 years of tradition. For example, members of a group of over 30 firefighters involved in an overview of Operational Risk Management training were asked how they made risk management decisions on the fireground. They stated that there was no consistent method used, that every individual has their own way of making those decisions, and that the policy statements on risk management about “risking a lot to save a lot” went out the window as the emotion of the moment carried their decision-making. Good decision making requires good training.

The difference between training in operational risk management (ORM) and policy statements is that with ORM, crews are trained to recognize hazards and manage the level of risk. Training in ORM also provides a standard process to identify hazards and assess risk that can be used by all personnel operating at an incident, from incident commanders to firefighters. Using a proven process allows personnel to make good risk management decisions more quickly. The result is higher levels of both safety performance and operational performance because the hazards that cause harm also cause delays in achieving tactical objectives.

Shift the focus

A comprehensive approach to managing safety is the foundation for improvement in safety performance and operational performance. The core element of occupational health and safety management systems is the implementation and use of a standardized method for identifying hazards and managing risk. The process of ORM can be used to manage risks that cause operational injuries and fatalities as well as those risks that cause illness, such as cancer and heart disease. The same process can also be used to recognize and manage the risks that cause mental and emotional distress leading to suicide, which has only recently been recognized as a serious problem in the fire service.

Whatever the reasons for the lack of improvement in safety performance within the U.S. fire service, it is time to make a serious effort to change how safety is managed and how firefighters are trained to manage risk. If we continue to minimize the way we manage safety and continue to train firefighters to take risks rather than manage risk, the same consequences will continue: tens of thousands of injuries and dozens of fatalities every year. Many if not most of these casualties could be prevented if the fire service would implement a comprehensive approach to managing safety and train firefighters how to manage risk.

About the Author

William Pessemier

Bill Pessemier is the former fire chief in Littleton, CO, and spent 30 years in the fire service. In addition, he was a professor with Oklahoma State University, teaching courses in political science and fire and emergency management. Pessemier has a master’s degree in public administration from the University of Illinois and a doctoral degree in public affairs from the University of Colorado. His dissertation focused on the development of a model of safety culture in the fire service. Pessemier has authored several articles on safety culture in the fire service that have been published in academic journals and presented at conferences around the world. He is the CEO of Vulcan Safety Solutions.