Health & Wellness: Positive Mental Health Culture

In a discussion with Western Springs, IL, Fire Department Chief Patrick Kenny, the subject of changing a culture came up. I have used the term “changing the culture” of the fire service in reference to behavioral health numerous times in presentations. However, Kenny, in passing on wisdom from others, asked, “What if they like their culture and don’t want to change?” That sure fits Chief Alan Brunacini’s adage, “Two things firefighters hate: the way things are now and change.”

When I started my career at 18 years old, I liked the way things were. Unbeknownst to me, my employer and co-workers were molding that young, naive mind of mine, and not in a good way. I worked with a group who I believed were great people; however, they were negative, thought the worst of people, including patients and co-workers, and never could look at the good in situations. Working long hours with no breaks and a lack of leadership continually fed this negative culture. This is how I look at behavioral health issues that are within the fire service, and, collectively, we must vastly improve—not “change”—the culture, so the premise of behavioral wellness in the fire service is accepted.

It’s complex

Although the initial concept of making positive improvements in the behavioral health culture seems simple, once you begin to dive in, you quickly can realize that you must be willing to change your own heart and mind and, most importantly, get acquainted with the idea of showing your own vulnerabilities.

Furthermore, the concept must start at the top. Without a sincere, honest and caring leader, this process will go nowhere. A sincere, honest and caring leader who serves the membership must be willing to have these important but uncomfortable conversations. It’s the initial step in improving the culture—allowing staff chiefs and company officers to be open and to share any experience without the fear of being deemed unfit for duty or being reassigned. If one is afraid to speak up, all will be afraid to speak up. Company officers must feel comfortable about addressing these critical conversations in the firehouse. Topics to discuss may include addiction(s), anxiety, alcohol and drug misuse, depression, traumatic stress, relationship issues and suicide, to name several.

There are very few firefighters, if any, from all over the world who don’t know of someone personally or through an acquaintance who has suffered one or more of these issues at some time in his/her life. Being one of those who suffered: It’s OK. It’s normal. No one is perfect. We must normalize being able to talk about these issues openly and candidly without fear of stigma.

That is why you must open your heart and mind. You must not be judgmental of others. If you can work on listening, understanding and withholding judgment of others, you will find yourself closer to others than further apart. That is what I truly believe that the fire service “brotherhood” and “sisterhood” is all about. It isn’t enough to put up posters and information that have phone numbers to employee assistance programs and suicide crisis lines and for relationship advice and about the dangers of alcohol, etc. It’s about sitting around the kitchen table as a crew telling stories, having a good cry, sharing both the highs and lows, just like a family, which we are.

When uncomfortable is good

Much of the time, meals at the firehouse are on your own, and cellphones, laptops and social media reign supreme. Just as firefighters use lived experience stories during training evolutions to reinforce important teaching points, you should use your life stories and struggles to reinforce that a) we are all here for each other, b) no one fights alone and c) someone might have some tips or tricks to assist you in your struggles. To accomplish this, you must show your own vulnerabilities, something that’s uncomfortable for many. Despite being uncomfortable, the benefit is three-fold. First, you improve the culture of behavioral health in the fire service. Second, you open up to help others who are struggling in their time of need. Lastly, you don’t grow as a person until you are uncomfortable.

It is unacceptable to leave things the way that they are in the fire service. This is a disservice to every firefighter—past, present and future—along with those of us who have struggled with mental health issues. You are not weak to cry at the firehouse table; you are strong. Weakness comes when we ignore it or speak of these things as a negative. Vastly improving our culture will save countless lives that we might never know about.

About the Author

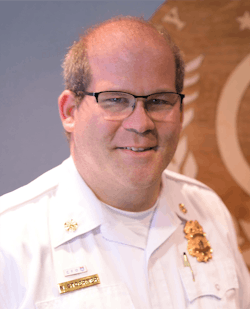

Nathan Stoermer

Nathan Stoermer is a suicide-attempt survivor, ardent supporter, and speaker on firefighter mental health awareness and suicide prevention. He currently serves as the Fire Chief in Greensburg, IN. Stoermer holds an associate degree in paramedic science from Ivy Tech Community College and a bachelor’s degree in fire administration from Eastern Kentucky University along with various fire and EMS certifications, including the designation as a Chief Fire Officer from the Center for Public Safety Excellence. He currently is enrolled in the Executive Fire Officer Program. Stoermer has spoken on firefighter mental health to firefighters of all ranks, to mental health professionals, to chaplains and to peer-support teams. Most recently, he participated in a suicide-awareness video that’s being produced by the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation. Stoermer conducts applied research into the causes of firefighter suicide along with what departments do to support their members. His article on addressing the concern of firefighter suicide appeared in Crisis, Stress, and Human Resilience: An International Journal.