Health & Wellness: Important Decisions from Gut Instincts

Consider this: It’s 1 a.m. when the tones ring out for a motor vehicle accident with one person

trapped. The location is a winding road in a wooded area. Cloud cover obstructs any potential moonlight. The air temperature is 48 degrees Fahrenheit.

On arrival, companies find a two-door car that collided with a tree. A young male is trapped in the driver’s seat, with the dashboard collapsed on top of him. He is wearing a seat belt and has visible facial injuries from impact with the tree and air bag deployment. The patient initially is alert and oriented x4, but his injuries will worsen the longer that he remains trapped.

With the temperature dropping, there’s a nagging feeling in your gut that each variable on scene is working against the patient. You and your team work quickly to extricate the patient, but as you transfer him out of the wreck, his medical status immediately declines.

A report is given to the medical team at the trauma center: “A 22-year-old male with crush injuries sustained from an MVA involving a car versus tree. He was trapped underneath the dashboard for approximately 25 minutes. Initial Glasgow Coma Scale score of 14, with pupils equal and reactive to light. He was wearing a seat belt, and air bags were deployed. After patient was extricated, his status quickly deteriorated. During transport, his Glasgow Coma Scale score decreased to 8, with pupils equal and reactive to light. Irregular, shallow breathing pattern, with a heart rate of 46 bpm and a blood pressure of 88/42 mmHg. No significant past medical history. No known medications or allergies.”

Every decision that’s made and each action that’s taken in the field and during transport assist in determining the outcome of an emergency situation. The sequence of events that unfold after the tones go off is a carefully choreographed mixture of standard operating protocols and clinical experience. With increased exposure to various emergencies, the ability to highlight important details in the field shapes your ability to prepare for and react to the unique challenges of each circumstance.

Although every call is different, over time, you are able to pick out familiar patterns between similar situations. For example, you can look at how a patient is trapped in an MVA and at that individual’s movements, mannerisms and other external factors and know the patient’s prognosis. At a structure fire or wildland fire, you become attuned to slight differences in the appearance of smoke, how the wind carries it, and the size and color of the flame, which helps you to anticipate its next move.

Those “gut feelings” that you experience are real. The network of nerves and neurological pathways that line the gastrointestinal system make up the enteric nervous system. Although the gut can’t make conscious decisions and body movements, the enteric nervous system directly communicates with your brain.

How do you enhance your ability to make decisions and trust “gut feelings”? The answer lies within what’s referred to as the gut-brain axis.

Gut-brain axis

Think of the gut-brain axis as a two-way radio, a communication system between the brain and spinal cord of the central nervous system and the nerves of the enteric nervous system. This axis links your ability to learn, interpret information and make decisions with the health of your gut.

When you’re in a structure fire, the gut-brain axis allows you to both communicate about what’s happening in your area as well as receive information from other areas. It works best when collaborating with the trillions of microorganisms (primarily, bacteria) that reside throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Although the exact composition and diversity of microbiota are unique to each person, these microorganisms play a significant role in maintaining one’s overall health, wellness and fitness. Bacterial colonization within the gut is affected significantly by stress, diet, environmental factors, use of antibiotics and exercise.

Current evidence indicates that duration, intensity, frequency and type of exercise affect microbiota composition and variety, which results in positive health benefits. When the tones go off, you don’t know the complex details of the emergency prior to arriving at the incident. Therefore, you must be physically and mentally prepared to respond to anything. Exercise training should include all components of fitness, including strength, speed, endurance, flexibility, power and agility.

Exercise

Recent studies found that aerobic exercise and endurance training increase the gut microbiota diversity and functional metabolism. High-intensity interval training has been shown to increase healthy gut microbiota composition. According to “The relationship between the gut microbiome and resistance training: a rapid review” (BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, Jan. 2, 2024), there also is a potential correlation between gut microbiome health and muscle strength performance. Thus, an exercise program that incorporates increased variation positively affects the microbiome health and gastrointestinal function.

Information from the enteric microbiota is transmitted to the central nervous system along the vagus nerve. This nerve directly connects the digestive tract, heart, lungs and airways with the brain. A component of the parasympathetic autonomic nervous system, the vagus nerve is responsible for stimulating “rest and digest” functions when you sleep and during other nonstressful situations. Conversely, when the tones wake you up in the middle of the night or during any other stress-inducing event, the sympathetic autonomic nervous system is responsible for causing the fight-or-flight response.

New research demonstrates that during increased physical activity or stress, there’s an increase in activity of the vagus nerve, which allows for more effective delivery of oxygen to working muscles. Thus, even during a fight-or-flight situation, the parasympathetic nervous system affects our ability to respond to a stressful state.

Not only do different forms of exercise increase vagus nerve tone, but changes to the gut microbiome also affect vagus nerve function. Therefore, as reported in “Exercise influence on the microbiome-gut-brain-axis” (Gut Microbes, Jan. 31, 2019), increasing vagus nerve health through exercise might increase enteric microbiota diversity and composition.

Stretches

To help to increase your vagus nerve tone and promote a healthy enteric microbiome, incorporate these stretches into your daily routine. Note: Stretching might be uncomfortable but never should cause pain.

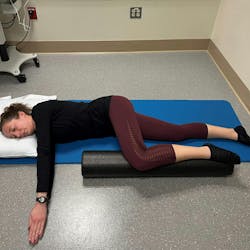

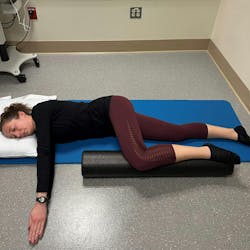

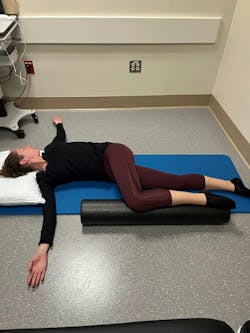

Open book stretch. This stretch is for the upper back muscles and uses a rotation motion of the upper spine. To stretch the left upper back muscles, lie on your right side. Your head should be supported, so the spine remains straight from the upper neck to the tailbone. Keep your right knee straight and bend your left hip and left knee. Place a foam-roller or a stack of two or three pillows under the left lower leg, supporting your left knee and foot. Bring both arms out in front of you to shoulder height, with palms together. The right arm doesn’t move throughout the exercise. Keeping your left elbow straight, rotate your upper back toward the floor as you also bring the left arm up and over. Your head also should rotate to look at your left hand throughout this exercise. Hold this position for 3–5 seconds and slowly return to the starting position. Complete six repetitions on each side.

Low quadruped stretch. This activity stretches your hips, back and shoulders. Start on your hands and knees. Look down at the ground while also keeping your neck in alignment with the rest of the spine. Without moving your hands or knees, sit back on your heels. To get more of a stretch, reach your hands farther out in front of you. Hold this position for as long as 30 seconds before returning to the starting position. Perform three repetitions.

Modified sit and reach stretch. This stretch targets the hamstring and groin muscles. Sit with your left leg out straight, at a 30-degree angle to the side. The right knee is bent in toward you. Keep your left knee straight and your pelvis on the ground throughout the stretch. The left knee and left toes should point up. Reach both hands out toward your left foot and ankle. Hold for about 30 seconds. Complete 2–3 sets on both sides.

Sitting piriformis stretch. This stretch targets your hip muscles. Sit on a firm surface with both legs straight out. Bend the right knee and cross your right leg over your left leg. The right foot should be flat on the ground. Keeping your back straight, pull your right knee toward your chest without moving the spine or pelvis. Hold this stretch for as long as 30 seconds. Complete 2–3 sets on both sides.

About the Author

Jessica Scott

Jessica Scott is a Doctor of physical therapy, a certified athletic trainer, and a tactical strength and conditioning facilitator. She received her undergraduate degree in athletic training and sports medicine and her Doctorate of physical therapy from Quinnipiac University. As the daughter of a firefighter, Scott grew up seeing the physical demands and requirements of the firefighting profession. Therefore, she started New England Tactical Sports Medicine, which is dedicated to improving the health and wellness of tactical athletes and provides rehabilitation services, educational seminars regarding injury prevention, and fitness programs to promote healthy lifestyles and improved physical performance.