We are in the midst of a crisis not seen since the outbreak of the 1918 influenza pandemic, commonly referred to as the Spanish Flu. The spread of the novel coronavirus and the disease it causes, COVID-19, is taxing healthcare and emergency services all over the world. Many leaders in the fire and emergency medical services are seeing their communities on lock-down in order to slow the spread of the disease. Chiefs are struggling to staff fire companies and ambulances as the virus spreads through their departments and members are hospitalized or placed in stay-at-home isolation.

This crisis could prove to be a stress test of your station’s infrastructure and built environment. Managers responsible for facilities management and in-house logistical support should make sure to document the pitfalls and pain-points they encounter as this nationwide disaster progresses in order to better prepare for any kind of emergency that may come in the future.

Are you ready?

As leaders in emergency services we should all be familiar with continuity of operations plans (COOP). Most of these plans revolve around natural disasters or other emergencies like hurricanes, earthquakes and fires. The scenarios addressed are often aimed at keeping units up and running for hours or days until repairs can be made or alternate accommodations can be secured. But do you have a plan for a pandemic that may last for months and that doesn’t fit into our normal vision of a disaster? The likely answer is no.

Most preparedness plans for fire and EMS agencies revolve around sustaining service to the community they serve for the short-term duration during an evolving disaster, and the initial response and recovery phases. These plans typically look to ensure core functions and maintain vital record keeping processes with the aim of restoring normal service delivery as fast as possible in conjunction with emergency management agencies.

This current crisis poses a unique challenge for leaders when it comes to maintaining facilities and providing a healthy station environment for our front-line service providers.

Departments in small or rural jurisdictions may find this challenge easier to overcome as the close-knit relationships with local support services and internal maintenance or repair supports quickly transition to this new normal. This may be more difficult for larger organizations as the support services they normally rely on face their own challenges and availability diminishes as the spread of the virus continues. More stringent measures may even be implemented to “flatten the curve.”

The reality is that in a disaster, emergency services facilities serve as the forward operating bases for public safety. Chiefs can’t just call it a day when things are not working like they normally do.

Weathering the storm

Renovations Needs of the U.S. Fire Service, published by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) in 2019, points to the effects of deferred maintenance and lack of investment in fire stations across America. Over 21,000 firehouses (43 percent) across the country were built over 40 years ago and are nearing – or are past – their designed life expectancy. Data collected by the NFPA for the fourth Fire Service Needs Assessment Survey points to a $70-$100 billion needed investment for fire service facilities.

With that knowledge in mind, we know that departments all over the country are facing challenges to keep their facilities safe and operational without this current crisis making things even more problematic.

Some of the challenges departments may be facing are a lack of personnel to repair and maintain facilities due to illness, mandatory isolation or restrictions on the ability of support staff to work. Many mid-size to large departments rely on shared resources for these services.

Local governments may have deemed much of their facilities' repair and maintenance staff non-essential as they have limited government services, shuttered buildings and transitioned office staff to work from home. NFPA 1500 - Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety, Health, and Wellness Programs - requires fire departments to have a system in place to promptly correct safety and health hazards and maintain facilities. Have you planned for these challenges or advocated for dedicated staff to be labeled essential in order to keep stations operating?

If these services are outsourced, does the contract contain language for situations like this, or is the vendor willing to maintain some level of service if it isn’t addressed in the contract? One way to ensure the ability of maintenance and repair crews is to make sure your agency, or the public works department, has prepared a response plan if they are staffing emergency operations centers or on call. Knowing how a clogged drain, leaking roof or broken apparatus bay overhead door will be repaired in an expedient manner while dealing with limited staffing and other restrictions ahead of time will allow emergency services to concentrate on our primary mission.

Another area of concern is life safety in facilities. What is you plan to keep sprinkler, fire alarm, extinguishers and cooking hood suppression systems inspected and in good working order? Facilities managers should reach out to the companies that provide inspections, testing and maintenance of these systems to address issues before they become emergencies while this pandemic continues to impact normal service delivery.

Many local governments have restricted businesses from operating in order to slow the spread of the coronavirus. This could have an impact on facility repairs or renovation and construction projects. Some contractors may have misinterpreted rules limiting work or elected officials may not have considered the impact restrictions may have had on their own core government functions. The Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency has identified essential critical infrastructure workers for the COVID-19 response. Although only a guidance document, it is useful in supporting arguments to allow business that provide supply, maintenance, and repair services to be allowed to operate in support of fire and EMS agencies.

US Department of Homeland Security

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency

GUIDANCE ON THE ESSENTIAL CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE

- Workers – including contracted vendors -- who maintain, manufacture, or supply equipment and services supporting law enforcement emergency service and response operations (to include electronic security and life safety security personnel).

- Workers who support the operation, inspection, and maintenance of essential public works facilities and operations, including bridges, water and sewer main breaks, fleet maintenance personnel, construction of critical or strategic infrastructure, traffic signal maintenance, emergency location services for buried utilities, maintenance of digital systems infrastructure supporting public works operations, and other emergent issues.

- Workers such as plumbers, electricians, exterminators, builders, contractors, HVAC Technicians, landscapers, and other service providers who provide services that are necessary to maintaining the safety, sanitation, and essential operation of residences, businesses and buildings such as hospitals, senior living facilities, any temporary construction required to support COVID-19 response.

- Workers supporting essential maintenance, manufacturing, design, operation, inspection, security, and construction for essential products, services, and supply chain and COVID 19 relief efforts.

- Support required for continuity of services, including commercial disinfectant services, janitorial/cleaning personnel, and support personnel functions that need freedom of movement to access facilities in support of front-line employees.

Preventing the spread

Needless to say, in the middle of a pandemic, infection control practices play a major role in stopping the spread of disease. Most firefighters' first thoughts don’t go to facilities planning and supply logistics when they think of infection control, but they can play a major role in reducing the spread of bacteria and viruses. The U.S. Fire Administration’s guide Safety and Health Considerations for the Design of Fire and Emergency Medical Services Stations addresses many health considerations. These include everything from passive and active cancer prevention measures (like the creation of green, yellow and red zones or the installation and use of point source vehicle exhaust systems), to addressing the spread of food and waterborne infections through specifying the performance criteria for kitchen equipment like dishwashers and refrigerators for kitchens.

Many of these program requirements are expanded on in NFPA 1581 - Standard for Fire Department Infection Control Program. The standard contains an entire section on facility design requirements. One of the most applicable sections during the COVID-19 crisis addresses something we all have heard about when we are interacting with each other: social distancing and keeping six feet apart. In numerous fire and EMS stations across the country, limited space has led to things like treadmills, exercise bikes and weight lifting equipment to migrate into bunk room or dormitories. Often this is done with the best intentions. Typically, fire stations designed before the 1990’s did not include dedicated gyms or workout rooms. As the fire service began to recognize the importance of health and wellness, apparatus bay gyms became popular.

When we started to recognize the risks posed by engaging in physical training in an environment polluted with carcinogens coming from diesel emissions and products of combustion transported back to stations on hose line, tools and protective gear, many stations saw the equipment move into bunk rooms because they were not used during the day and frequently have climate control. Many bunk rooms also become homes to storage cabinets and shelving for EMS supplies and fire prevention materials.

Many of our predecessors did not anticipate our roles to expand or future programming needs like in-house physical fitness space. This becomes a problem as the shared sleeping quarters become crowded and bunks are pushed closer together or are replaced with bunk beds. Bunk beds have inherent risks associated with them that may lead to injury. Single bunks spaced closer than six feet apart may contribute to the spread of disease as we sleep. People can produce airborne droplets as they snore or cough. To address this, NFPA 1581 requires 60 square feet per bed. That translates into a six-foot by 10-foot box per bed. This leaves the familiar sounding six feet between each person and adequate space to move about when the alarm sounds.

Bunk rooms should also have functioning heating, ventilation and cooling (HVAC) systems. Managers should ensure that routine upkeep is performed. Check for standing water and mold in HVAC systems and change or clean filters regularly.

Considerations regarding infection control in the kitchen include specifying of nonporous countertop surfaces, plus storing and cooking food at proper temperatures by maintaining refrigerators and cooking appliances.

Keep it clean

Storage of reusable medical equipment and open medical supplies should be separated from living spaces to prevent contamination by staff. Contaminated material and medical waste should be stored in a dedicated space and in proper containers like red bags and sharps containers.

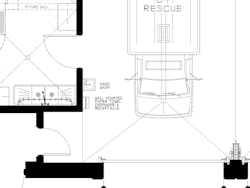

Fire station designers are now including hand-washing stations throughout new station builds. They are locating them in apparatus bays, and work areas where there are contaminated materials, as well as adding a second dedicated hand-washing sink to kitchen plans. If your station does not have adequate hand-washing capacity, it should be supplemented with waterless alternatives like hand sanitizer dispensers.

Supply availability may be challenging for departments during this outbreak. The media has shown the stories of supermarket shelves cleared of disinfectant, paper towels and toilet paper. Does your department have policies in place to deal with these shortages? Many larger agencies may have their own warehouse facilities that stock these items, while others may have products shipped directly to stations, and smaller departments may even shop for these supplies in retail stores.

Managers responsible for supply logistics are facing challenges. Departments should consider rationing supplies and limiting access to where these items are stored in order to ensure supplies last as long as possible. Many will have to seek alternate sourcing for items. This can often be facilitated through the logistics branch of an activated emergency operation center. Departments should consider reaching out to local or regional breweries, distillers and chemical companies that may have changed their operations to produce hand sanitizer. Another option is to reach out to your community through social media to solicit supply donations.

Looking forward

As we progress through this historic event, those that support frontline first responders will be tested to their breaking point. As we face each trial, we should make sure to document it. As the crisis begins to resolve we should take time to evaluate these challenges and look to improve policies and procedures to deal with the next stress test of our facilities and ability to support operations. These tests should also fuel requests for funding of station improvements, expansions and replacements.

Planning for the future of emergency service facilities should include consideration of supply reserves and expanded support staff. In a disaster, emergency services facilities become akin to military forward operating bases and should be afforded the same supply and resilience support. This will be incredibly difficult for departments that are already facing issues resulting from deferred maintenance and lack of investment as budgets will surely be cut due to the funding needs of the coronavirus pandemic emergency response and recovery efforts. Department leaders and facilities managers will need to advocate for dedicated relief funding to ensure that our stations are ready to face future challenges.

About the Author

David Kearney

Dave Kearney is a captain with the Philadelphia Fire Department and has over 25 years of experience in the agency.

A member of the PFD’s Technical Support Unit, he works with the city’s Department of Public Property, design professionals, contractors, and other stakeholders to advance PFD’s vision related to the construction, operations, and maintenance of the department’s 68 operational and support locations.

A first responder for 34 years, Dave has served as a firefighter, paramedic, code inspector, instructor and company officer. He serves on several NFPA technical committees, and on city-wide workgroups related to healthy built environment, stormwater management, and GIS.

A graduate of Neumann University, Kearney holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Public Safety Administration.