Fire Law: Public Access to Fire Stations as Public Buildings

The right of citizens to access public property comes up in a number of contexts, ranging from concerns over employee privacy to the right to engage in peaceful protests. From the fire service perspective, questions commonly arise over the ability of firefighters to exclude the public from a fire station given its status as a public building. The flip side to the same problem arises when citizens demand entry, intent on filming what they see.

The issues are more than just theoretical. A growing number of departments have experienced a visit by citizen-journalists who revel in their role as “First Amendment Auditors.” These folks are on a mission to educate public officials regarding the fact that the First Amendment protects the right of all citizens to film in public areas on public property. These folks are willing to push the limits of the law to prove their point, including being arrested and filing suit in federal court.

Like many challenging issues that confront us, understanding the law and having a well-drafted policy put us on a path toward a good outcome. Not understanding the law and/or not having a policy before a problem occurs is a recipe for disaster. In this case, the disaster may come in the form of a viral video, a First Amendment lawsuit or both.

The basics

Government-owned and -operated fire stations generally are considered to be public buildings. So are court houses, prisons, schools and even the White House.

The fact that a fire station is public property does not mean that the public has an unfettered right to enter and roam about.

Government, as a building owner, has the right to establish reasonable limitations on access to government properties. The absence of a law or policy that establishes limitations on the public’s right to access government property creates an ambiguity. The ambiguity allows a member of the public to object to any specific limits that a given employee decides to impose on a given day to a given individual. Said another way, when a firefighter attempts to stop a person from entering a firehouse and/or filming, the lack of a policy creates a situation that is ripe for a claim of a First Amendment Right violation.

The solution is for fire departments to have policies that specify what parts of its buildings are open to the public as well as any hour of the day and/or day of the week that restrictions are applicable. The policy should be well-researched to ensure compliance with any state and local laws.

For example, a typical policy might:

- prohibit all visitors from any part of the fire station except for certain designated locations (such as a lobby area, apparatus floor, etc.) during certain hours (example: 8:00 a.m.–8:00 p.m.)

- require a firefighter to accompany visitors beyond the lobby for their safety and for the security of apparatus, equipment and members’ personal property

- prohibit access when firefighters are on emergency responses, training or otherwise not available

- provide exceptions to allow for emergencies and with written permission from the fire chief

The policy should be supported with signage that indicates restricted areas and time-of-day/day-of-week limitations. Training of all personnel on the policy and how to deal with common problems is advisable.

Clear and enforced

Armed with a clear policy that can be shown to a visitor (or to a police officer, so an uncooperative person can be escorted from the premises), the pressure is off of the firefighter. The citizen then is left with the option of challenging the department’s policy, as opposed to challenging the authority of a firefighter or company officer, who merely was trying to do the best that he/she could in the absence of a policy.

The really good news: First Amendment Auditors are well-trained in First Amendment law. They know that if the department has a clear policy that’s supported by signage and is enforced, the auditors’ job is done. The absence of a policy, personnel who are trained in the policy and signage will be viewed as opportunity to provide the department with a painfully teachable moment in First Amendment law.

About the Author

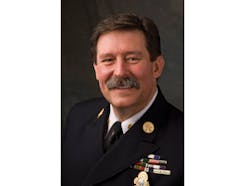

Curt Varone

CURT VARONE has more than 40 years of experience in the fire service, including 29 years as a career firefighter with Providence, RI, retiring as a deputy assistant chief (shift commander). He is a practicing attorney who is licensed in Maine and Rhode Island and served as the director of the Public Fire Protection Division at the NFPA. Varone holds a master's degree in forensic psychology from Arizona Statue University. He is the author of two books, "Legal Considerations for Fire and Emergency Services" and "Fire Officer's Legal Handbook," and remains active as a deputy chief in Exeter, RI. Varone is a member of the Firehouse Hall of Fame.