Using GIS to Site Fire Stations and Improve Incident Response Times

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Standard 1710 established minimum time standards for the first-due engine out of a career department for a residential fire. Some departments, however, are not meeting that standard, sometimes taking upwards of nine minutes to reach a fire. When a home is going up in flames or someone has been hurt, every minute counts. There are a number of reasons why a department might have long response times, especially in volunteer departments where firefighters might need to first travel to the station before responding. Siting stations in areas closer to emergencies is one way to reduce response times—This is where GIS comes in.

Geographic information systems, or GIS, attach data to specific locations and use maps to display patterns. Types of data could include the locations of fire hydrants, home addresses, hiking trails, power lines that are vulnerable to high-speed winds, or potentially hazardous materials, such as lithium-ion battery storage or microgrid infrastructure. Any fire department that has a forested park within its response territory should pursue GIS mapping for any biking or hiking trails. Emergency calls happen on trails all the time; everything from sprained ankles to bike crashes and falls to concussions. A long-time hiker or biker may know the official name of the trail, but will the first responders? Without GIS data, how does one describe or find a specific spot amidst a sea of trees? Departments can print out and hang these maps on the wall of a station or use them in browsers on mobile devices for easy access in the apparatus or in the field.

Modern GIS mapping enhances a department’s pre-incident planning by incorporating relevant documents and floor plans, operational workflows, and specialized features for sharing information with the public. Additionally, almost all public safety answer points and 911 dispatch centers already use GIS data as a comprehensive source of local addressing. Centralizing all this information in a single system can help with both acute responses and proactive emergency planning.

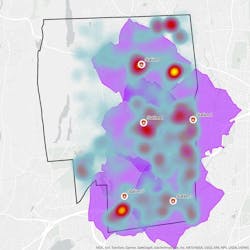

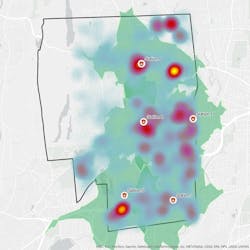

In terms of station siting, GIS can use municipal growth patterns and community-specific risk factors to determine whether emergency response facilities are located where they are most needed. By collecting, processing, and analyzing incident location data, a GIS specialist can pinpoint each response on a map. Advanced GIS spatial analyses can compile several years-worth of pinpoints into a heat map that visualizes clusters of call density. An additional analysis, known as response time mapping, utilizes GIS-based roadway centerline data that contains travel parameters such as speed limit, distance, and travel direction, to estimate how far an apparatus can travel in four to six minutes from each station and produce a polygon outlining that range. If there are enough incident hot spots that occur outside the four to six-minute travel radius, departments should consider how to increase coverage, including relocating an existing station or building a new one.

Architects often perform feasibility studies for existing stations and new sites. Many studies evaluate a site or existing building’s potential for renovations, additions, or relocation. Some determine which factors impact response times. Times could simply be a product of distance, but narrow bridges, railroad crossings, or a high volume of passenger vehicles can also cause delays. A site could also be ideal in terms of size, shape, topography, available utilities, and road frontage, but the collected GIS data and response time patterns might reveal it to be unusable. GIS could potentially even identify sites that had not previously been up for consideration by looking at the map’s gaps in coverage. These sites may be better suited for safe response/return paths, on-site vehicular maneuverability, and future expansion potential.

If investing in GIS seems like a frightening expenditure, consider teaming up with the local water district, as most already have their infrastructure mapped. Knowing the precise location of every fire hydrant and diameter of its associated main line is useful information when two engines are trying to pull from a six-inch-wide source when a 10-inch main is around the corner.

There is no upper limit to how much data a GIS map can hold. A map with half a million data points is perfectly feasible; it’s just a matter of devoting the resources to collecting and processing the raw information. These maps are dynamic, living documents that should be updated often. If a new business or landmark comes into play, the map can and should be updated with the official and colloquial names. If a new housing development changes an area’s population density, GIS specialists can use census data to update the maps and re-evaluate whether the entire district is appropriately covered.

Picking a new site for a station is a multi-year commitment that requires time, money, and political will. Switching locations in the middle of this process could be devastating. Use GIS to make sure you get it right the first time.

About the Author

Christopher Kobos

Chris Kobos, PMP, GISP, is the Director of GIS Services at H2M architects + engineers. As a GIS professional with more than 20 years of experience, he works directly with clients to provide technical guidance and project management services for municipal, utility, public safety, and private sector GIS projects. He oversees and offers technical direction to a group of GIS analysts and specialists and is responsible for the continuous development and maintenance of technical competencies with the industry-standard software and cloud platforms required for successful solution delivery. His extensive experience serving emergency service clients and all levels of municipal governments lends itself to a unique perspective on the client business needs and the most appropriate procedures for delivering high quality, effective consulting products and services.

Dennis A. Ross

Dennis Ross, AIA, is a Technical Advisor and past Emergency Services Market Director at H2M architects + engineers. Previously, he was a founder and co-owner of a nationally recognized, award-winning firm exclusively dedicated to the design of emergency response facilities across North America. He has over 40 years of focused experience in construction and development, which allows him to assess projects from multiple points of view.

He is NCARB certified; a member of the American Institute of Architects, National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), and the International Code Council; licensed in 14 states; and an honorary member of the Kingston Fire Department. His expertise in public forums, project management, land use, budgeting, construction and focus on solutions to difficult problems has enabled him to knowledgeably write and speak on a variety of emergency services station design issues. Dennis has authored many articles and presented at even more conferences. In 2001, he received the Business Council of New York State’s and National Federation of Independent Business’ annual award for “New York State Small Business Advocate of the Year.”

Dennis is currently serving on the NFPA Technical Committee on “Emergency Responders Occupational Health,” which is tasked with developing a new Standard for Contamination Control, NFPA 1585. Dennis led the task group for Chapter 5, Emergency Services Organization Facilities. In 2022, he was appointed to the NFPA - Architects, Engineers, Building Officials (AEBO) commitee as an Executive Board Member.