Calling a MAYDAY is a complicated cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skill set that relies on a radio and the communication system, both human and hardware, that gets the call for help.

Thanks to the cooperation of the Anne Arundel County Fire Department (AACOFD), the Maryland Fire Rescue Institute (MFRI), and the Laurel Volunteer Fire Department (LVFD) the firefighter MAYDAY concepts presented by Clark (2001, 2003) and Clark, Auch, & Angulo (2002, 2003) were put to the test and passed with high marks. The Mayday Doctrine theory is based on an analysis of the engineering, psychology, physiology, and training aspects of a firefighter calling a Mayday. This analysis used jet fighter pilot ejection doctrine models as the foundation (benchmark) for developing firefighter Mayday Doctrine.

Over a three-day period 91 firefighters and officers experienced what it may be like to call a MAYDAY using their cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skills. The overwhelming conclusion by all who participated was that everyone needs this type of training and it needs to be repeated throughout your time in the service. Battalion Chief Dave Berry of the Anne Arundel County Fire Department conducted the training for Battalion 3 on all three shifts. (photo1) The drill consisted of classroom lecture and hands on practice. Each class size was about 15 students, two drills per day (AM and PM) six drill deliveries total.

Chief Berry used the mayday articles as the foundation for the lecture portion of the Battalion Drill, "Calling a MAYDAY." In addition he asked 110 firefighters "What Makes You Call a MAYDAY?" From this extensive list he narrowed the MAYDAY Parameters down to six words: Fall, Collapse, Activated (low air or PASS device), Caught, Lost, Trapped. To drive the need for Mayday training home, the Seattle, Washington Fire Department videotape of the three firefighter near misses was presented. This tape clearly illustrates how quickly a firefighter becomes incapable of calling the MAYDAY because of carbon monoxide that reduces cognitive decision-making and small motor skills and the psychological reluctance of firefighters to call for help. An additional videotape of the near LODD of an Anne Arundel County firefighter brought the point home that this can happen to you and you only get one chance to call MAYDAY correctly.

The most elaborate prop simulated falling through the floor. This prop was designed and built by Engineering Technician Donny Boyd of the MFRI. The prop consists of a ramp the firefighter crawls up. (photo 2) At the top is a teeter board, which when the firefighter crosses the center of gravity, tilts forward; (photo 3) dumping the firefighter into the third part of the prop, the ball pit. (photo 4) The ball pit is actually filled with cut up swim noodles because they were less expensive than balls and are more durable. A key concern was safety of the firefighter. No one was hurt but the firefighters knew that they had suddenly fallen into something. The transportable prop was build for under $1000.00

The second prop, simulating a ceiling collapse, was made of chain link fencing that was dropped over the firefighters as they crawled under it. (photo 5) Two instructors then stood on the fence restricting the firefighters movement and making it impossible for them to escape.

The classroom lecture also covered the three AAFD procedures for calling a MAYDAY. First, push the emergency identifier button (EIB) on the radio. This captures the channel for 20 seconds, gives an open mike to the radio (in other words the firefighter does not need to push the talk button on the radio), and sends an emergency signal to radio communications identifying the radio. Second, announce MAYDAY, MAYDAY, MAYDAY. Third give LUNAR: L location, U unit number, N name, A assignment (What were you doing?), R resources (what do you need?). The classroom portion of the drill took about 90 minutes. Chief Berry distributed a job aid, the size of a business card, to all participants; it listed the six MAYDAY parameters on one side and the three procedures for calling a MAYDAY on the other side.

The hands on portion of the drill took place in the basement of the fire station. The MAYDAY props were set up before the drill and the area was placed off limits so no one knew what they were to experience. The four MAYDAY props simulated: falling through a floor, being pinned under a ceiling collapse, getting lost / trapped in room, and becoming stuck while exiting the structure.

The third prop was a small bathroom with a sink and toilet about 5x6 feet. (photo 6) A hose line with nozzle ended in this room. Once inside, the door was closed and a wooden chock placed under the door. This made it impossible for the firefighter to exit the room.

The fourth prop simulated becoming stuck while exiting a building. (photo 7) The prop was a piece of wire rope with a slip loop that was dropped over the firefighters SCBA bottle. As they continued crawling the loop tightened up making it impossible for them to move forward. Try as they may, they could not get loose. (photo 8)

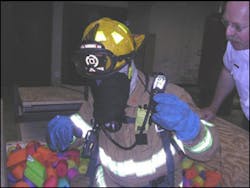

One at a time the firefighters were brought to the outside basement entrance. They were in full turnout gear with SCBA. At the entry point they were given the assignment. "This is a simulated fire with IDLH conditions. You and an imaginary partner are to follow this attack line into the kitchen. When you arrive your assignment is ventilation." The firefighters were reminded of LUNAR, put on air and their face piece blacked out. (photo 9) The door was opened. They were told to go on hands and knees and follow the hose line.

The firefighters immediately had to crawl up the ramp (spotters were on either side), when the teeterboard tilted; they fell into the ball pit. The firefighters were expected to call a MAYDAY. If that was not their first reaction, the instructor prompted them, "What just happened to you?" Answer required, "I fell into something." Prompt, "What are you to do if you fall?" Answer required, "Call a MAYDAY." Prompt, "Correct, do it."

After the firefighters correctly pushed the EIB, said MAYDAY MAYDAY MAYDAY, and gave LUNAR they were told that they were done and were helped out of the ball pit. The instructor then reset the radio. They were told to go down on hands and knees again, crawl to another line, and continue their assignment. After crawling about 15 feet, the chain link fence was dropped on them. The instructors stood on the fence making it impossible to escape. Their correct response was to call a MAYDAY. If the firefighters struggled for more than a minute, they were prompted again. After calling the MAYDAY, they were released, their radio was reset, and they were told to continue their assignment. After another 15-foot crawl, they ended up in the bathroom at the nozzle; the door was chocked closed. This put them in the lost or trapped MAYDAY parameter. If after two minutes of trying to get out they did not call a MAYDAY, they were prompted. After the correct response, they were let out of the bathroom and the radio was reset. Next, they were told to find a nozzle on the floor outside the room they just left, then exit the building by following the line. The line took them around a metal fence/guard rail to a wheelchair ramp that led to the exit. As they turned the corner, a wire rope was dropped over the firefighter's SCBA bottle without their knowledge. After crawling 6 feet, the rope tightened, and they were stuck. After a minute of trying to get loose if they had not started to call the MAYDAY, they were prompted.

Lessons learned: At the first prop, most all the firefighters had to be prompted to call the MAYDAY. Their first instinct was to get out of what they had fallen into. The instructors did not let them get out. Their next challenge was pushing the EIB. This proved to be difficult for most of them and caused frustration and anxiety. The anxiety was evident by the increase in their breathing rate. The frustration was evident when some tried to remove a glove to find the button. Instructors did not allow this. They were prompted, "You just burned your hand. Put the glove back on." Most tried reaching down into the pocket to activate the EIB that usually proved unsuccessful. Some had to take the radio out of the radio pocket, in many cases this manipulation of the top of the radio caused them to change the radio channel. (photo 10) The longest time to successfully push the EIB was 2 minutes. Because of the frustration and anxiety, the LUNAR report was not always given correctly. The frustration and anxiety were most likely due to the fact that this seemingly simple skill of pushing the EIB was not easy. Pushing the emergency identifier button was challenging because the radio sat too far down in the radio pocket, gloved hands made it very difficult to activate the EIB, and the radio was a new style to the department.

At the second prop, the firefighters quickly realized they were not getting out of whatever had fallen on them, so few needed to be prompted to call the MAYDAY. This time restricted movement challenged them because the fence was all around them. Many had to remove the radio from the pocket. Since they had performed the EIB skill once before, they knew they could do it, so they just kept working at it. As the firefighter's EIB skill proficiency level increased, their LUNAR transmission was more accurate.

At the third prop there was no restriction on them physically. Many tried to break down the door; we did not let them do that. Most still had to remove the radio to activate the EIB. They gave LUNAR, but few reported that they were in a bathroom. Only one needed to be prompted to call the MAYDAY after about 2 minutes of just sitting in the room.

At the fourth prop, they were tired and quickly realized their forward movement was stopped. In most cases the "swim technique" did not reveal the rope, so they called a MAYDAY. Their LUNAR usually did not include the fact that they were now trying to exit the building they were still reporting "division one, kitchen, ventilation, trapped."

Only one firefighter was observed to have no difficulty pushing the EIB in the pocket; he even did it without lifting the pocket flap. During the second drill period, Firefighter J.B. Hovatter was observed having not put his radio down in the pocket. He had taught himself to put the pocket flap down inside the pocket and hook the radio clip over the chest strap of the SCBA. This technique positioned the radio halfway down in the pocket keeping the controls outside the pocket, but still securing the radio to the firefighter. He quickly activated the EIB every time. It was decided to teach this technique, "The Hovatter Method", to all remaining firefighters, whose performance level increased dramatically. (photo 11)

A discussion session was held with the class after each drill to show what the props were and to get feedback. Overwhelmingly, they said it was an important learning experience and they all agreed the drill should go department wide.

What some participants said: Division Chief Allen Williams, Health and Safety Officer for the AACOFD who observed the drills said: "Hopefully firefighters will do all they can to not need to call a MAYDAY. However, firefighting is dangerous and the risk is there. Firefighters are reluctant to call MAYDAY. The training forced them to call MAYDAY. The training was excellent. The training is a very good risk management strategy."

Battalion Chief Dave Berry said: "This training shocked them into calling a MAYDAY. It took some of the bravado out of them. It doesn't matter what rank you are we can all get into a situation where we need to call MAYDAY. The drill became the great equalizer. In training it is difficult to shock a person into calling MAYDAY without hurting them; these props can do that. I know now that my battalion can call a MAYDAY if they have to."

Captain Leroux said: "We needed to be coached through calling a MAYDAY; it did not come naturally. We had machismo and self-doubt. Should I or shouldn't I call MAYDAY, I'll be embarrassed. We learned how important it is to call MAYDAY quickly while you still can think and explain where you are and answer questions. It is my crew and I that go in and will be using this skill. When you get in a MAYDAY situation you are going to be so stressed out - calling MAYDAY has to come natural and this training will help."

A firefighter: "When they dropped that fence on me I realized I was done. You are calling people to come get you out. I had to concentrate on getting to the button and calling a MAYDAY."

Some veteran firefighters said, "?it was the best training we have ever received in our career."

Lessons learned:

- For the MAYDAY call to be completed it must be received by someone in communications, then communications must repeat back to the firefighter the information reported. This is the only way the person calling the MAYDAY will know their message was received correctly.

- The hands free feature of the radio is useful, but if the mike is turned facing the firefighter's coat the message will become muffled.

- The firefighter must speak loudly, clearly, and distinctly to be heard and understood.

- If LUNAR is not the normal day to day communications sequence for talking on the radio it may not come naturally to firefighters under MAYDAY conditions.

- In some cases the radio EIB did not reset correctly. The next time the EIB was pushed the three beeps sounded indicating the open mike was on but there was no transmission.

- It was learned that AACOFD communications could reactivate the captured channel and open the mike for an additional 20-seconds and repeat opening it as needed.

- The AACOFD is working on purchasing user-friendly firefighting gloves. This will help in using the radio.

- Situational awareness can be compromised very quickly in a zero visibility environment.

- The fact that you decided to call a MAYDAY can tax your higher cognitive thinking, like where you are and what you are doing, which are important facts for the RIC.

Calling a MAYDAY is a complicated cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skill set that relies on a radio and the communication system, both human and hardware, that gets the call for help. A failure in any component part of this system can be disastrous. We need to study, test, train, and drill the entire MAYDAY Calling system if we expect it to work when we need it.

Recommendations

First, practice calling MAYDAY. Can you push the EIB in 5 seconds with all you gear on? What happens when you push the EIB? (Does the radio channel change, who receives the EIB signal, where is it received, what do they do with the information?) Can you get to the radio when you are covered with debris? Where does the mike need to be so you can be heard? How loudly do you need to talk?

Second, include MAYDAY calling as a subset drill in all training where firefighters are put into simulated IDLH conditions. At a minimum, in rookie school and throughout their service, firefighters need to practice calling Mayday as often, if not more then, they practice-tying knots. Our bodies and minds need to be shocked into MAYDAY parameters repeatedly so the correct response becomes natural and instantaneous.

Third, get communications involved. How many times do dispatchers practice receiving and responding to a MAYDAY call? You do not want your real MAYDAY call to be the first time the radio operator gets to test their MAYDAY skills, radio equipment EIB function, and MAYDAY procedures.

Finally, whether you are the rookie firefighter or fire chief, if you put on SCBA and enter IDLH environments, you need to drill on "Calling a MAYDAY."

Authors Note: After the pilot deliver of the drill in Battalion 6, the department moved the class to the county fire-training academy. Chief Berry was assigned to conduct the drill for the entire department. As of the end of June 2004, all 700 career and 300 active volunteer personnel in the Anne Arundel County Fire Department had gone through this "Calling a MAYDAY Drill". Congratulations to the first fire department in the nation to do so.

References

- Clark, B.A. (2001) "Mayday Mayday Mayday: Do firefighters know when to call it?" Firehouse.com

- Clark, B.A.; Auch, S; Angulo, R, (2002) "When would you call Mayday Mayday Mayday?" Firehouse.com

- Clark, B.A (2003) "We have permission to call Mayday" Firehouse.com

- Clark, B.A.; Angulo, R.; Auch, S. (June 2003) "You must call Mayday for RIT to work: Will you?" Fire Engineering p35-39