Gender & the Fire Station

Today’s fire stations serve not only as efficient command centers but also as homes for the firefighters, 24/7. Firefighters’ ability to protect their citizens is directly influenced by the quality of the environment in which they live and work. As such, fire departments around the nation are constantly seeking to improve these environments so they can enhance the level of service they provide their communities, retain and recruit the best firefighters, achieve their operational goals, and manage their budgetary constraints.

Similarly, fire station designers are constantly looking at ways to improve social interaction, strengthen the sense of camaraderie and promote team building. Along with this, designers are looking at the need for, and level of, privacy in the living quarters portion of the fire station. This leads to the importance of carefully designed public and private areas. An ideal situation allows for personnel to interact with their fellow firefighters when necessary but also to enjoy a sense of privacy when needed. This privacy is key when it comes to study areas, sleeping quarters, lockers, changing areas, restrooms and showers.

Gender-specific vs. gender-neutral

With an increased number of women joining the firefighting ranks, there’s a need to rethink how we design fire station living environments. Departments are now looking at these changing demographics and trying to assess their impacts over the next 10 to 20 years, or more. This has led designers to seek various means of providing privacy for fire personnel with gender-“specific”, “-neutral” or “-friendly” facilities.

As more and more women enter the fire service, we see departments either trying to retrofit existing facilities or design new facilities to meet the increased need for privacy in living quarters. Areas that have the most sensitivity or need for privacy are sleeping areas, locker and changing areas, restrooms and showers.

The traditional gender-specific approach of one dormitory, one locker room, one restroom with multiple toilets, sinks and showers is now giving way to a range of other options. Some say that one advantage to the dormitory-style arrangement, with multiple beds in one large room, is the sense of team-building and camaraderie that can occur in this setting.

This has led some departments to create gender-specific dormitories. Even though the configuration of the dormitory room itself is very efficient, having to provide dormitories for each sex requires careful estimating of gender mix and often means adding additional beds to allow for shifts in numbers of men vs. women.

As a result, other departments have taken an approach that modifies the dormitory so it becomes more gender “neutral.” One way this can be done is to add partial height walls between beds and possibly curtains that offer additional privacy. In some departments, there is standardized “modesty gear” (i.e., shorts and T-shirt) issued to each individual to be worn for work and sleeping.

The dormitory space can often contain additional elements, such as lockers and study areas, with lockers designed so they can also contain storage space for bedding. These can be configured in such a way as to provide a degree of privacy between beds.

Restrooms can be configured in a number of ways. The traditional approach is a gender-specific facility with multiple toilets, sinks and showers. These are often combined with lockers and changing areas. This approach requires determining what the ratio of men and women will be over the life of the facility, and usually results in building more facilities than are actually used.

Crucial to a successful fire station design is a careful analysis of short- and long-term staffing needs. This includes determining number of crews and staff per crew; procedures to be followed during crew changes, such as taking showers and changing of clothes; the number of part-time and full-time firefighters; and the role the facility will serve in times of major emergency events. As mentioned earlier, it also requires anticipation of the ratio of male and female firefighters. It is also important to consider other functions that occur in the facility, such as training or staff meetings. In some instances, dormitories are designed with built-in Murphy beds that can be folded up, allowing the space to be used for other activities.

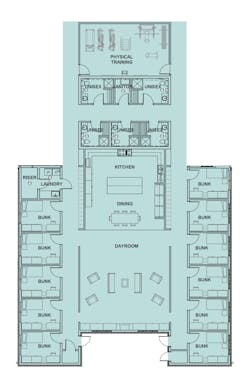

While we have seen a number of approaches to designing sleeping areas, restrooms and locker areas to address privacy and mix of gender, we are seeing a higher percentage of departments opting for a more gender-neutral approach. This will often include individual bunk rooms with study areas included, single-occupancy toilets that include showers (that can be used by either sex) and remote lockers that are often located in an adjacent hallway, with changing occurring in the bunk rooms or restrooms/shower areas. One of the main advantages of this approach is that it allows a department to design the facility for a set number of firefighters regardless of their gender, even if the ratio of men to women changes over time. It also allows the highest degree of flexibility for the individuals regarding their personal space and allowing them to come and go without disturbing the other crewmembers. Further, by placing the lockers in a remote location, they can be configured with enough lockers for multiple shift changes. This can allow the bunk beds to be oriented so they get natural light and ventilation that could be individually controlled.

The example illustration shows how this approach can be arranged so it literally wraps around a central shared kitchen and dayroom space. It is critical that the configuration of all the living quarter elements are arranged to allow maximum interaction between spaces, while providing an appropriate level of privacy for all crewmembers.

We have seen cost-saving benefits for developing stations with single occupancy restroom/shower facilities with common area lockers over traditional dedicated gender restroom/shower facilities. This is typically a result of the reduction in actual area needed and reduced total quantity of plumbing fixtures. Comparing the sample design to a station with a gender-specific restroom/shower facility with a similar quantity of lockers and plumbing fixtures (completed for a different fire department) demonstrates that the single-occupancy approach achieved a reduction of 40 percent of the required area. This not only translates to reduced cost for the project, but can also allow for a tighter, more compact floor plan, improving flow and travel time across the station.

Create a good space for all

When designing for today’s fire station living quarters, it is important to carefully consider a variety of factors. These range from the departmental goals and culture to anticipated growth projections and specific operational conditions. In addition, it is important to consider the gender and related privacy issues we have discussed. Departments across the country are finding that a comprehensive response to these issues will result in a highly flexible environment that creates a more livable environment for all crewmembers.

Director of Architecture and leader of Mackenzie’s public projects team, Jeff Humphreys has more than 20 years of architectural experience. Humphreys specializes in public safety and emergency response facilities and has been project lead on nearly all of Mackenzie’s public safety projects over the past decade. He takes an active role in the design community, and regularly presents at fire and police design conferences. He is a board member for the Oregon Fire Chiefs Foundation and serves on the IAFC Environmental Sustainability Committee.