The 2016 Station Design Conference, held in Anaheim, CA, brought together nearly 200 fire department officers, municipal leaders, architects and manufacturers to learn about and share trends and innovations for new emergency response facilities. The results were a fantastic exchange of information and ideas.

One of my highlights from the conference was the keynote presentation by Paul Erickson, principal, LeMay Erickson Willcox Architects, and Chief William Pearson with Atlanta Fire Rescue. In 15 years of covering fire station designs, I have seen some positive, significant changes in new fire stations. Their keynote on Hot Zone Design, however, is probably the most significant challenge since designated fitness rooms highlighted the importance of firefighter health and fitness. Erickson and Pearson sent a strong message about the need to address firefighters’ exposure to carcinogens and toxic materials inside the fire station.

Additionally, the conference offered a variety of educational sessions, tackling everything from how to build community support to using technology to improve response times to site construction costs. Designing a new fire station for the next 50 to 75 years, when responsibilities keep changing, is a tall order, but all attendees agreed the information was valuable and the time well invested.

Here, we share with you some of the indispensable knowledge offered at the conference.

— Janet Wilmoth, Special Projects Director

The Journey to Your New Fire Station

Presentation by Ken Newell, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, Stewart-Cooper-Newell Architects

All the world’s great, time-tested structures began with a firm foundation. The same is true for great fire stations. Ken Newell’s presentation introduced the audience to the foundational components necessary for the planning, design and construction of a modern fire station.

As the opening session for the conference, Newell provided the attendees with a broad look into many critical issues and topics that would help any fire department plan a station that will stand the test of time. Some of these topics included:

- Land: Newell addressed how proper location is determined and what some of the obvious and not-so-obvious evaluation factors may be, such as subsurface geotechnical and environmental concerns.

- Architect: He covered proper expectations of the architect, along with the benefits that could be realized by involving the architect early, as well as the importance of selecting an architect with a long, successful reputation in fire station experience.

- Money: Newell covered several questions related to finances—Where will you get money? When will you need it? How much can you get? How do we develop a comprehensive, total project budget?

- Program: The session addressed how to identify the different, programmatic zones of the fire stations, along with ideas on how to separate critical zones, such as the public and private areas.

Further, Newell used the recently completed, award-winning Danville, VA, Fire Department Headquarters & 911 Center as a case study to point out how the proper foundational decisions are made in a successful project.

For more information, visit http://fire-station.com.

Community Support—or Die Trying

Presentation by Dennis Ross, AIA, architect and co-owner, Pacheco Ross Architects, P.C.

Building community support for a fire station project is an integral part of the design process. In his session, Dennis Ross demonstrated current trends that both departments and communities are utilizing for (and against) projects, illustrated both good and bad practices, and presented concrete solutions to avoid hidden pitfalls, find opportunities, understand public support and get to a “yes” vote in one piece.

First, Ross explained that building community support is like running a campaign, where grassroots and personal contacts are key. Additionally, he underscored that it’s vital to start building support early, as setbacks can be measured in years. There is a clear cost for time in architecture projects, as doing nothing has consequences in the form of cost escalation, continued maintenance and morale reduction.

It is important to define the size and scope for the project early on, so expectations are clear, particularly related to costs, Ross said. People are going to want to understand the funding method, so ensure that the financial issues are clear. Develop a cohesive message, be transparent, and control the rumor mill with facts and professionalism. Further, Ross said, it’s important to use multiple platforms (blogs, social media, etc.) to share information. Perhaps the best approach, however, is the basic “boots on the ground” in which firefighters go door-to-door to promote the project, he said.

Due diligence is a key factor in achieving project buy-in, so it’s important to keep community members knowledgeable about each step of the process. Explain the project’s program, prove that the land acquisition was wise, and show a clear plan for the future and that the design is unique to your issues.

In the end, it’s important to keep the goodwill going, Ross said. Don’t lose momentum. Maintain the hard-earned support through school and community events or even tours of the station.

For more information, visit www.pra-pc.com.

Technology Innovations to Boost Performance & Reduce Response Time

By Christopher S. Kehde, AIA, LEED AP, principal architect, LeMay Erickson Willcox Architects

“The future is now,” according to Christopher Kehde as he discussed the application of innovative technologies in fire and rescue services and fire station design. Beginning with an overview of recent publications from NIST and NFPA regarding “Smart Firefighting” and standards for digital data management, Kehde reviewed how technology can be integrated into what he called “Smart Fire Station Design” to improve response times and boost performance in a variety of ways, including:

- Response: The flow of information from dispatch to the responding personnel is central to fire and rescue services and is critical to save lives. Computer-aided dispatch (CAD) systems can now deliver detailed information including incidents narratives, maps, traffic information, hydrant locations, and floor plans to the fire station and to mobile devices including laptops, tablets and smartphones.

- Station Alerting: Integrated alerting systems within the fire station can provide audio and visual alerts throughout the building. Alerting systems can be coded per responding units and companies; alerts and data can be forwarded to mobile devices; safety interrupts can override TV’s and shut off gas ranges; and alerts can trigger countdown clocks tracking turnout time.

- Training: WiFi can provide personnel the opportunity to complete online training in the station on tablets or laptops, and simulated scenario training can use mobile device applications to create realistic response scenes for incident command and response training.

- Building Automation Systems (BAS): Smart building systems allow for mechanical, plumbing, and electrical systems to be monitored and controlled online. This allows for real-time tracking of the building systems energy performance.

Kehde added that Smart Fire Station Design should include flexible infrastructure to allow the station and systems to evolve with technological advancements.

For more information, visit http://lewarchitects.com.

The Particulars on Particulates: Air Quality Systems

Panel led by Jim McClure, principal, Firehouse Design & Construction

Jim McClure led a panel discussion with Paul Erickson, LeMay Erickson Willcox Architects; Chief William Pearson, Atlanta Fire Rescue; and Candace Wong, principal, Ten Over Studio, Inc., discussing the types of air quality systems, their specifications, certifications and options for size, placement and connections within the station. McClure later explained some of the key takeaways from the panel, noting first that this is all about cancer prevention, as diesel exhaust is a known carcinogen. He emphasized that the statistics are not in firefighters’ favor, with there being six major chemical components and 24 minor ones in diesel exhaust.

McClure explained that the three different types of technologies on the market today are next to impossible to compare. He stated that when you read the promotional literature—which is typically written by marketing people and vetted by attorneys—it refers to the different standards, testing, codes and agencies with which the companies comply. The trouble is, he said, that they don’t use the same standards, so you are left comparing oranges, apples and bananas. He underscored that it is up to firefighters to become knowledgeable enough to ask the right questions to get the answers you need.

Additionally, McClure acknowledged that these decisions sometimes come down to money, as a department may only be able to install what they can afford. The key, he said, is to ensure that you do something to protect firefighter health. McClure shared a final takeaway that actually came following the presentation. A firefighter from a California department came up to him and said, “As a cancer survivor, I respectfully but forcefully disagree with the philosophy of buying what you can afford.” His recommendation was to buy the best. McClure added that this means that you really have to do your homework to determine what works for your department.

For more information, visit www.firehousedesignandconstruction.com.

Program for Success

Presentation by J. Lynn Reda, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, principal with Hughes Group Architects

Lynn Reda explained that the success of any fire facility project starts at the beginning, with the program. The program identifies spatial needs for people, equipment, storage—anything and everything that goes into a station. However, a good program doesn't stop at just area; it identifies characteristics of the spaces as well. Heating and cooling, power, lighting, adjacencies, minimum dimensions, sustainability features, furniture—all of these can and should be considered and documented as part of a well-developed program.

Reda noted that program documents should be easy to read, organized by area of the building, and incorporate area for both net (useable) spaces as well as gross (mechanical, electrical, circulation, wall thickness) spaces. The “gross-up” factor should vary depending on which areas of the building are being documented. As such, the gross-up for apparatus bays will be less than that of office or dormitory areas. Apparatus bays are large open spaces, with circulation incorporated into the area, whereas offices have many walls and corridors.

The final program becomes the basis of the construction budget for the facility. Initial construction budgets can be based on the overall area of the building identified by the program, using an appropriate cost per square foot that reflects the type of construction and architectural aesthetic desired. In the case of budgets developed for future capital improvements, factor in an amount for annual escalation of costs.

Once the design process is underway, she said, it is important to monitor the area of the building against the program, on a space-by-space basis. Understand where increases and decreases are taking place. She advised to not be fooled by a “close” bottom line number. Document decisions to eliminate or add spaces to the program as memories (and committee members) fade over time.

Taking time in the beginning to develop a carefully considered program will lead to a successful station at dedication—and well into the future.

For more information, visit http://hgaarch.com.

Site Construction Costs

Presentation by Bradley Mull, AIA, CSI, CCS & Joe Weithman, AIA, CDT, LEEP-AP, Mull & Weithman Architects

Bradley Mull and Joe Weithman delved into the topic of site construction costs, which can account for 20 to 30 percent of fire station construction costs (hard costs). Factors that can influence costs include soils, site topography, environmental issues, traffic engineering requirements, storm drainage, zoning requirements, existing conditions (structures and utilities), special requirements of authorities having jurisdiction (AHJ), site size and location, as well as the station design itself, they said.

Testing existing soils and environmental factors can help minimize site costs, and provide the information for the project team to make informed decisions as they move through site acquisition and the station design process.

They underscored that maintaining open communications through the site development process allows all involved to have an investment in the project and in the process. Further, they encouraged using your available resources throughout the site selection and design process, noting that the design team can assist in evaluating site options, specifying the required testing, identifying fees and costs upfront, and maintaining open communications with the AHJs.

Correctly budgeting for site costs can make or break your project. They explained that your design team should take a detailed cost-estimating approach to eliminate many of the pitfalls of square foot estimations. It is important to include project size, location and time/inflation factors into your overall budget. Overhead, profit and general requirements typically account for 20–25 percent of the construction estimate. Understand and make the proper appropriations for project budget, estimate and construction contingencies. The contingency relates to the construction cost estimate, and varies from 10–20 percent depending on the estimate level of detail. In general, a 10 percent construction contingency is recommended to safeguard against the unknowns at the beginning of construction.

Finally, they advised that departments use allowances to serve as placeholders in the construction documents for items with an unknown amount. An example would be for x number of cubic yards of engineered fill. Alternates can be used to keep options open, depending on bid results. Typical site alternates include pavement material upgrades, increased parking areas, site training features, security enclosures and monitoring, and landscaping.

For more information, visit www.mw-architects.com.

Revealing the Secrets of a Success Bidding and Construction

Presentation by Ray Holliday, AIA, ASLA, APA, principal, and Jennifer Bettiol, project manager, BRW Architects

When it comes time to design and build a new fire station, there are many factors to consider. Ray Holliday and Jennifer Bettiol explained that before design, and even before hiring your design professional, it is important to consider your delivery method options and the construction process, including the owner risks and involvement. They outlined the three primary types of project delivery methods:

- Design-Bid-Build (most common): The design professional is brought on board at the beginning of the project to complete the design and construction documents prior to bidding and hiring of the contractor.

- Construction Manager at Risk: The construction manager is brought on board early in design in order to offer constructability and cost-estimating assistance. Then, when it is time to bid the project, the construction manager assumes the role of general contractor and releases the construction documents for subcontractors to bid.

- Design-Build: A Design-Build team, consisting of the general contractor and architect, are hired as a single entity under one contract. At bidding, once again, the construction documents are put out for bid for subcontractors costing.

Holliday and Bettiol noted that each delivery method has its advantages and disadvantages. The Design-Bid-Build method offers the owner the most opportunity for input in design decisions; however, as the contractor is not brought on board until after bidding, the cost estimating is supplied by the architect based on their experience and the construction price data available for the area. The Construction Manager at Risk method offers costing and constructability during the design phase; however, there are typically fees associated with this delivery method, and the contractor may have to cut elements out of the project to meet this budget. The Design-Build method offers the owner a budget-friendly option; however, it involves the least amount of owner input, and does not have the checks and balances offered by the other two methods.

Holliday and Bettiol added that with each phase of the project, it is important to identify the roles and responsibilities of each entity (the owner, the architect, and the contractor). Before beginning the project’s design, a fire department or municipality needs to consider what risk and involvement it would like to assume. The owner must consider the balance among schedule, cost, scope, quality and risk. Through a foundation of good communication, planning and an understanding of the goals for the project, roles for each responsible party can be established and understood. Combine these elements, they said, and the successful design and construction of a new station is well within reach.

For more information, visit www.brwarch.com.

Until next year …

Station design is a complex process, but with the right team, led by a knowledgeable architect, you can achieve a station that fits the needs of the community and the firefighters who live and work there. A new fire station is not only the largest investment a department will make, but also requires an eye to long-term growth and future responsibilities. It's about training for unknown challenges and the health and safety of department personnel. Invest the time to learn trends, innovations and save costly errors from experienced resources, while networking with other departments. That's what the Firehouse Station Design Conference is all about. For more information about any of the material presented here, please visit fhstationdesign.com or contact the individual architecture firms.

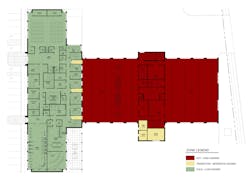

Sidebar: Keynote: Hot Zone Design: Contain the Contaminants

Presentation by Paul Erickson, AIA, LEED AP, senior principal, LeMay Erickson Willcox Architects, in collaboration with Captain William Pearson, Atlanta Fire Rescue Department

During their keynote address on Hot Zone Design, Paul Erickson and William Pearson challenged conventional industry approaches with the latest thinking on designing stations for the health and well being of the crew. Specifically, they emphasized that firefighters are being exposed to some of the most toxic, cancer-causing carcinogens in firefighting history, prompting the question, “How do we keep our most precious assets safe?” The concept of Hot Zone Design identifies these health risks—including the exposure to smoke, toxic chemicals and carcinogens—as well as how the toxins are conveyed back to the station and transmitted to others within and beyond the building.

Erickson and Pearson addressed how Hot Zone Design focuses on controlling the entry and handling of carcinogen-contaminated personnel and equipment into the building, employing the idea of creating and then managing three levels of exposure to contaminants:

- Hot zone (red): high hazard

- Transition zone (yellow): moderate hazard

- Cold zone (green): low hazard

Erickson and Pearson explained that this approach to design addresses the arrival of carcinogens in the building, and prevents the inadvertent migration of contaminated materials within the structure; however, design thinking and departmental protocols must work together. With this in mind, they offered the following strategies: Contain the contaminants, separate occupants from contaminants, control or limit crossover, pay attention to transitions, and focus on the highest hazards.

Erickson added that “one event doesn’t change a person’s life, but the repeated exposure will kill you,” making the Hot Zone Design all the more important in order to improve the life quality and longevity of the next generation of fire and EMS professionals.

Additionally, Special Project Director Janet Wilmoth lauded Erickson’s work with the Firefighter Cancer Support Network to better understand and share the health risks firefighters are exposed to and how to effectively remove and contain the contaminants in the station.

For more information, visit http://lewarchitects.com and www.firefightercancersupport.org.

Sidebar 2: Lessons from Pre-Conference Sessions

Design for Performance

Christopher Kehde—Principal, AIA, LEED AP with LeMay Erickson Willcox Architects—addressed the topic of designing fire stations with performance goals in mind. The key to finding the path to the station you need, Kehde said, is to know where you are and where you want to go with regard to a variety of factors, including response time; training; special considerations, such as an EOC or community outreach center; sustainability; firefighter health and safety; accreditation/ISO; designing the 50-75-100-year station, meaning a longstanding station that is both durable and flexible enough to adapt to changes; technology; camaraderie and culture; and department identity. Kehde reminded attendees that the ultimate goal is to be able to talk to your architect about each of these topics early in the design process to ensure that your station achieves its goals, for the station, department and the community. To read the full coverage of this session, visit firehouse.com/12209680.

Value Engineering

Value engineering is an often-misunderstood concept in architecture, but it is a critical component of any station design project. This was the key message from David J. Pacheco, AIA, NCARB, and co-owner of Pacheco Ross Architects, PC. Value engineering is about finding the appropriate balance between the minimum cost and the maximum quality for a project. As such, architects and the fire personnel working on a fire station must consider a variety of factors and how they affect this balance—factors like the initial project price, overall scope of the project, life-cycle costs and minimum time to get the job done. “Value engineering is NOT cost-cutting. That can be a component, but it’s really about making optimized decisions,” Pacheco said, adding that it’s less about cutting costs and more about bringing maximized value to the project. Pacheco offered some common strategies for value engineering related to three key areas: 1) architectural fees/scope; 2) design; and 3) construction. To read about each area, visit firehouse.com/12211263.

Accessibility Codes & Fire Stations

Ensuring that your new fire station is up to date on the various national and regional building codes can be an arduous task, particularly because these codes can overlap and are often in flux. Eric Schaer, principal, AIA, and Forest Hooker, senior associate, both with TCA Architecture Planning, addressed this issue as it relates to accessibility issues. Schaer and Hooker underscored that accessibility issues are complex, often have multiple authorities having jurisdiction, and involve codes that can result in differing interpretations. As such, it is important to work with an architect who understands the requirements for a fire station. Schaer and Hooker noted that the Department of Justice (DOJ) is ultimately responsible for enforcing requirements set forth by the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, and the DOJ can still audit the building even if it has received all the necessary approvals by local building officials. They offered several examples of codes to be mindful of during design as well as exceptions to the codes. To read the full coverage of this session, visit firehouse.com/12211473.

1-on-One Takeaways

We asked some of the attendees who participated in the Station Design Conference 1-on-One sessions to provide their feedback about the experience speaking with a team of nationally recognized fire station design architects from around the country. Following are some of the common takeaways from the 1-on-One sessions as well as overall thoughts on the conference.

Quick Takeaways

- “Time is money. Have a plan and educate the key players about the need now vs. money later.”

- “Importance of performance-based design and building codes and accessibility.”

- “Be involved in the project design process.”

- “Keep contaminants as far away from living areas as possible. A good idea is to locate those areas opposite from living areas, using the bays as a buffer.”

- “ADA compliance is key.”

- “Maintain communication and stay involved.”

- “No need for air locks if the mechanical systems are properly designed.”

Conference Feedback

“This has been a great conference with a lot of information to absorb in a short time.” —George Tockstein

“The success of your future station involves key players, from your firefighters to the architects.” —Tommy Madrio

“The Station Design Conference offers information on projects from their infancy all the way to near completion. Fantastic conference.” —Brandon Franck

“The right design is not the one ‘iconic’ building but the one that delivers form, function, comfort and safety. Equip your department with the right team.” — Alejandro Wolniewitz