There are, generally speaking, three categories of people in the fire service: those being led, those aspiring to lead and those leading. And we can safely state that the fire service is an entity that is bilaterally steeped in strong traditions and searching for progressive means to improve its performance.

All three types of people are affected daily by the decisions made by one or all of the others, with decisions made by those leading holding the most influence overall. It is no superfluous claim that a leader’s leanings toward tradition or progress influences decisions, department direction and morale. Leaders in particular have enormous responsibility. They are charged with serving two principal masters—the external community and the internal community. The needs and demands of these two communities can be contrasting to varying degrees. Pleasing these communities when they are in concert is a monumental task. Pleasing them when they are in conflict can be formidable.

Maintaining equilibrium takes a special person, or people, in each of the three categories of fire service people. Leadership experts theorize as to whether leaders are born or made. Candid self-reflection can be used to establish which category each of us favors, but we all do well to study leaders in order to maximize our leadership quotients.

The following influential leaders—one steeped in the rich history of the fire service, one not affiliated with the fire service, and one well-known to the reader—are offered as primers to expanding your leadership skills.

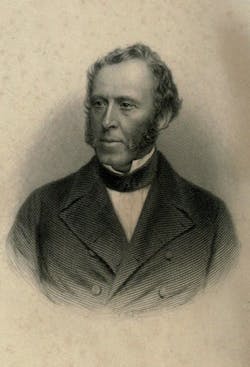

1. James Braidwood

Braidwood (1800–1861) is considered the father of the modern fire service. At 23, he was appointed as the first fire chief of Edinburgh, Scotland. This position came about after several disastrous fires in Edinburgh. Braidwood set about to elevate the professionalism of the Edinburgh fire service. Many of his ideas form the foundations of how we still fight fires today. Braidwood’s innovations included

- Recruiting men 18–25 years old with a building trade

- Introducing the interior attack as a means to contain a fire

- Working in teams of two

- Servicing pumping apparatus after every fire

- Monthly testing of fire pumps

- Regular service testing of fire hose

- Promoting centrally located fire stations

He also authored the first known text on “modern” firefighting—On the Construction of Fire-Engines and Apparatus, The Training of Firemen, and the Method of Proceeding in Cases of Fire—reprints of which are still available for reading today.

Braidwood was described as an able tactician, skilled administrator, heroic firefighter and caring leader. He successfully navigated the balance between protecting the community, being a good steward of the equipment and funding provided, and looking out for his people. Braidwood is also credited with instilling daring and courage in his firefighters, establishing mandatory training to improve skills, regular meetings with his officers to maintain clear lines of expectations and communication, and fighting off pressure to reduce staffing as a cost-cutting measure. His 1852 year-end report voiced concern about compensation for firefighters injured and killed in the line of duty (Hashagen, 2015).

Braidwood went on to lead the London Fire Engine Establishment (LFEE) in 1833, introducing many of the modern principles he implemented in Edinburgh. These principles included high pay and operational efficiency. Braidwood ably led the LFEE until he was killed in the line duty at a warehouse fire on the Thames River in 1861.

For two excellent reads on Braidwood, see Paul Hashagen’s comprehensive article on Firehouse.com and pick up a copy of Braidwood’s book. Both make fascinating reading that provides a remarkable insight into many of the practices and traditions that underpin the American fire service today.

2. D. Michael Abrashoff

In June 1997, D. Michael Abrashoff, a 36-year old naval officer and U.S. Naval Academy graduate, was assigned to command the U.S.S. Benfold. The Benfold is one of the Navy’s Arleigh Burke class destroyers. These warships are multi-mission, complex vessels designed for anti-aircraft, anti-submarine and anti-surface warfare. The crew consists of 310 sailors. Abrashoff was the most junior commanding officer in the Pacific Fleet, and the Benfold held the dubious distinction of being the worst performing ship in the Navy. Its performance metrics in all categories, from combat readiness to safety, were abysmal. Morale was poor, the ship was not in fighting trim and the weakest area of performance on the struggling ship, the engineering department, was an area Abrashoff had no experience in.

In one short, intense year, Commander Abrashoff took the poorest performing ship in the Navy and turned it into the top performing ship in the Navy. He accomplished this amazing transformation using a set of 11 leadership principles that he calls the “leadership roadmap."

The core of Commander Abrashoff’s style was creating an environment where people “… felt safe, empowered and supported.” (Abrashoff, 2002). His passionate focus was on the factors he could influence: his crew’s attitude. By seeing the ship through the crew’s eyes, he replaced the traditional management principles of command and control with commitment and cohesion. Abrashoff’s success is rooted in his ability to convey a vision that “… every individual shares the responsibility of achieving excellence” (Premier Speakers Bureau).

Abrashoff’s success is well-chronicled in two books that should be required reading for all fire officers: It’s Your Ship and Get Your Ship Together. The information and lessons that play out in both volumes transcend all generations and provide fire service leaders with invaluable insight into motivating firefighters while meeting the service demands and requirements of the community.

3. Your influential mentor

This is where you get to apply real-life experiences to strengthen your learning journey. While we can’t meet Braidwood, we do, to this day, emulate the virtues he espoused regarding service. If you have had the opportunity to read Abrashoff (highly recommended), attend one of his workshops, or meet him in person, you can’t help but be drawn to his enthusiasm and genuine passion for extracting excellence through empowerment.

Take elements from Braidwood and Abrashoff, mix the two together and the result is a rock solid base for successful leadership. Now add your own seasoning to the pot—someone you know personally and admire. Make a list of the traits that make them inspiring to you. What is it about their leadership style that makes you willing to follow them? Typically, people are looking for structure and consistency. They want to know what the rules are, have a say in the direction of the group, fair treatment and a leader that demonstrates a level of care. Typically you will find specific traits of your own personality that draw you to that type of leader.

The synergy among Braidwood, Abrashoff and your most influential mentor may not appear obvious at first, but consider this: All of these leaders had talents, skills, knowledge and a keen sense of maximizing human performance to get people to follow them. Braidwood, when building the LFEE, was charged with developing a full-time fire department (Edinburgh used a part-time, on-call model). He recognized the need for “structured discipline and a sober staff” due to round-the-clock operations. Braidwood specifically recruited former Royal Navy sailors because they were used to discipline and day and night watches (Hensler). Abrashoff, immersed in the U.S. Navy, inherited a crew of demoralized sailors who saw only drudgery and dead ends. Braidwood built a world-class professional fire department (two to be exact), and Abrashoff rebuilt the morale and performance of over 300 sailors on one of the most technologically advanced pieces of machinery known to humankind. The fact that both successful leaders had connections to the Navy is both ironic and fascinating when one considers Braidwood turned to the Navy for reliable personnel and Abrashoff took on a downtrodden crew and laid a path to excellence that is a model for all.

In my own experience, the list of mentors was near impossible to pin down to one. The man who set me on my path to the work ethic I have was my father. The fire service leaders who have influenced me in one way or another include Larry Gaddis, Danny Irvine Sr., William L. “Butch” Johnson, Ralph Turner, Donald Windsor, George Higgins, Jack Walters, Jim Fletcher, Jim Lesnick, Louie Schaub, Bill Ale, Andy Johnston, Les Adams, John Best, Jim LaMay, Lenny Fitch, Del Seelye and Tom Carr. Most of these names are unrecognizable to the fire service at large, but they were the people who dealt with me on a daily basis at one time or another in my career, providing me with little nuggets of wisdom and examples that fused to form an elastic bond of knowledge that serves me well to this day. They were the people who espoused the traits and virtues that Braidwood, Abrashoff, Alkonis, Brunacini, Carter, Lasky, Sendelbach and Salka talk about from the more visible stage.

In sum

To put it succinctly, good leadership is as much about observing as it is being observed. And while there is no “magic bullet” to excellent leadership, there are plenty of examples you can follow to develop a successful skill set. As you consider your leadership development (a perpetual journey), read Paul Hashagen’s outstanding article on James Braidwood, pick up a copy of Braidwood’s musings on fire department operations, be sure you read (or reread) Abrashoff’s volumes, and observe your mentor(s) with intense scrutiny. You’ll come away with the best of the basics for leading in today’s fire service. Good luck on your journey and LEAD.

References

- Abrashoff, D. M. (2002) It’s Your Ship: Management Techniques from the Best Damn Ship in the Navy. Warner Books, New York.

- Abrashoff, D.M. (2005) Get Your Ship Together: How Great Leaders Inspire Ownership From the Keel Up. Penquin Group, New York.

- Braidwood, J. (1830) On the Construction of Fire Engines and Apparatus, the Training of Firemen, and the Method of Proceeding in Cases of Fire. Bell & Bradfute, and Oliver & Boyd. London.

- Hashagen, P. (March 31, 2015) Rekindles Hall of Flame: Superintendent James Braidwood. Firehouse. http://www.firehouse.com/article/12053438/rekindles-hall-of-flame-superintendent-james-braidwood

- Hensler, B. (2011) Crucible of Fire: Nineteenth-Century Urban Fires and the Making of the Modern Fire Service. (pp. 11-13). Potomac Books, Washington, D.C.

- Premier Speakers Bureau. (n.d.) Michael Abrashoff Bio. http://premierespeakers.com/michael_abrashoff/bio

John B. Tippett Jr.

John Tippett, CFO, FIFireE, is the director of Fire Service Programs for the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation (NFFF). He was previously the interim chief for the Charleston, SC, Fire Department, where he served since 2009. Tippett previously spent 33 years with Montgomery County, MD, Fire and Rescue. He has extensive experience as a company officer, operations battalion chief, safety officer, instructor and chief officer. His past experience also includes 10 years with Maryland Task Force 1, a FEMA US&R team, with five years as task force leader. He has a bachelor’s degree in fire science and a master’s degree in emergency services management. Tippett has also worked extensively on national firefighter safety initiatives, including introducing crew resource management to the fire service and the National Fire Fighter Near-Miss Reporting System. He writes and lectures frequently on firefighter safety, decision-making, leadership, risk management and tactics. Tippett is an at-large board member on the International Association of Fire Chief’s Safety, Health and Survival Section, holds a certified health and safety officer credential through the Fire Department Safety Officers’ Association (FDSOA) and has earned a Chief Fire Officer Designation from the Center for Public Safety Excellence. He was the 2006 recipient of the George D. Post Instructor of the Year from the International Society of Fire Service Instructors.