Note: This article is part of the Firehouse 2024 Station Design Supplement. To read the entire supplement, click here.

Gaining community consensus around an idea rarely is easier than gaining consensus around the issue of response times: Faster is always better—or is it? The real answer to the question for fire departments and EMS agencies (as well as law enforcement and public works) is much more complex. Budgets, land availability, “best use” of available parcels, neighboring concerns, site conditions and preparation, and staffing all can play a part in the process of making facility-location decisions. Although response-time performance is a significant concern, it also is important for leaders to address the other factors that can affect the suitability of a site.

Response-time standards

Which components of total response time can be affected by decisions that pertain to facility location?

Facility design can affect the ability of first responders to react to calls and go to emergencies. Facility location can affect how long that it takes firefighters to drive to calls or incidents. Location won’t affect call processing, readiness or getting to the actual incident once members are on scene.

Although many things affect an agency’s response times to individual calls, analyses should focus on getting to as many incidents as quickly as possible. This brings into play the idea of fractile performance. This is a fancy way of asking the question: From this set of facility locations, what percentage of calls can members get to in a predefined number of minutes? For example, what percentage of a department’s calls can it get at least one unit on scene in a maximum of four minutes of drive time?

Does your community have defined response times? Are those response times part of a master or strategic plan? Have your community’s leaders signed off on them? If not, what response-time objectives will you use to do your analysis?

Another way of asking questions in relation to response times might be: What is your department trying to achieve? Does your department want to minimize response times? Must the department ensure that it has overlapping coverage of areas of high call density? Is the department affected by time of day or even seasonal fluctuations in demands for services? Regarding the latter, consider a beach community and how different demand is when summer season is in effect.

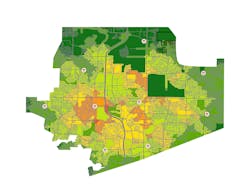

GIS to find facility locations

What is geographic information system (GIS) software? Esri’s website defines GIS as “a system that creates, manages, analyzes and maps all types of data. GIS connects data to a map, integrating location data (where things are) with all types of descriptive information (what things are like there). This provides a foundation for mapping and analysis that is used in science and almost every industry. GIS helps users understand patterns, relationships and geographic context.”

What this means for those who want to determine where the best possible site(s) might be for a new facility is that they have a powerful tool that can take in a massive amount of information and provide analytically derived answers to key community questions. The most effective way to conduct a response-time study (aka a deployment study) is to use a GIS coupled with 3–5 years of

call-for-service or incident data. Typically, these data can be extracted from a spreadsheet or database file that’s in a computer-aided dispatch system or a records management system and imported into GIS software.

While collecting the data that are in a GIS, one must work with the team to determine what question(s) are trying to be answered or what idea is trying to be proved? Questions that you address might include:

- Given the growth that occurred in a community, where must a facility(ies) be added to maintain the capability to deliver a first unit on scene in a maximum of four minutes of drive time?

- Can an existing station(s) be consolidated while a new building is built, to reduce the overall number of stations, which would allow staffing or supervision in stations to be increased?

- Where should a facility that reached the end of its useful life be moved to improve the capability to deliver critical services to the community?

- If all ALS transport units are moved to a central station, could it be guaranteed that a paramedic could be sent everywhere in the community in no more than eight minutes of drive time, assuming at least one unit is available?

- Must every change make the department faster or better? Are slower overall response times acceptable if it means that responding units can be staffed more safely?

It’s most important to frame a question in terms that the broad community can understand and that enable analyses to address stakeholder goals and concerns.

What output should you derive from GIS software? These powerful systems can provide two important tools for a team to use as it works with stakeholders to move the project forward. The first tool comes in the form of maps and other graphics that can be used to visually portray the effects of various alternatives. The second is encompassed in statistical and numerical outputs that can be used to analytically demonstrate the effects of various options. Both tools can provide powerful demonstrations of the effects of various site choices. Examples of the outputs include:

- Fractile performance (i.e., what percentage of calls could the department get to in x minutes and y minutes of drive time?).

- Number of stations overlap what percentage of calls?

- Are the department’s 10 biggest call-generator locations covered by one or more locations?

- How does each new alternative compare with what the department currently does?

- Where are the optimal sites for the next facility?

This list is by no means exhaustive, but it should provide a starting point from which

the team can build out its question(s) in support of the community and its stakeholders.

When you have sites to consider

Once a team extracted the analyses from the GIS software, with the results that are described above, those people now face the task of assessing the sites that resulted. What kinds of things should the team look for when it reviews the options?

- Is the site large enough for the facility that must be constructed?

- What’s the road access on and off of the site?

- Are sight lines adequate, and do they allow for safe responses?

- Is there capability to create a signalized ingress/egress at the site?

- Are there appropriate utilities that are proximate to the site that’s under consideration?

- Does the community own the land that’s identified as a potential site(s)?

- Are there wetlands or other limitations to using the full lot?

- Are there other environmental impacts to consider?

- Will zoning requirements affect the site?

- Is the site already used for something that generates tax revenues?

- Are there competing uses for the site?

- In addition to call volume, will the site(s) enable the department to address specific community needs or concerns?

- Does placement of a facility at a site allow the department to expand on an existing municipal campus?

These and other community-specific criteria can be entered into a matrix (e.g., Excel document) and used to score the potential site(s). Remember, weighting of the various factors is a community-specific concern. Some might favor response times over competing uses. Others might put more stock in taxable uses compared with municipal uses.

Compared with ISO

First-response facility location analysis improved dramatically since the days when departments and their collaborators used compasses on printed maps to draw 1.5-mile circles to approximate the Insurance Services Office (ISO) engine company response circumference—which historically was used as an approximation as to how far a horse team could pull a steam engine before tiring. With today’s modern fire apparatus, signalization, GPS, closest-vehicle response and other technologies, determining the best location for an emergency facility is more important and much more easily driven by the extensive data that are available in most communities. The ISO approach also ignores the potential for today’s systems to allow departments to automatically redeploy first-response units dynamically, based on current conditions and demands for service. Leaders in first-responder agencies, as part of their efforts to deliver the levels of service that are demanded by their community and its challenges, must ensure that their analysis and recommendations focus on meeting the complementary and, sometimes, competing objectives of safety, response times, budget and staffing. When leaders and their teams do their homework, they can improve by a significant amount the likelihood that a project will be approved and will begin its journey toward completion.

Travis Miller

Travis Miller, MS-PPA, has worked with the public sector as an economist, analyst and consultant since 1990. A key focus of his career has been to help fire/rescue/EMS agencies to determine the “best place” to put mission-critical facilities. Miller’s clients have included some of the largest metropolitan communities, hundreds of suburban communities, and rural districts, all of which span a breadth of service delivery environments and risk issues. The focus of his practice is to help public safety leaders to address stakeholder concerns and objectives early in the process, to enable leadership to focus on working with their architectural and engineering partners to achieve the best project possible. Miller is the principal of Criterion Associates.