Fire Law: Firefighters, Overtime and the Fair Labor Standards Act

It is hard to imagine a law that impacts fire department operations more than the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). If that sounds like an overstatement, consider this: What would the staffing in most paid fire departments look like if overtime was not a concern? What benefits might a volunteer fire department be able to offer if it did not have to worry about inadvertently turning volunteers into employees, who then would be entitled to minimum wage for all of their donated time?

Enacted in 1938, the FLSA did not fully apply to state and local government until 1985. Since then, the FLSA has played a major role in determining whether firefighters are entitled to overtime, the hours that they must work before being eligible for overtime, the hours that are compensable, the overtime rate, limitations of benefits for volunteers, and the rules that govern such common fire service practices as substitutions/shift trades, comp time, paid details and compensation for on-call time.

Although the impacts of the FLSA on fire departments are many, it is important to understand the most likely reasons why FLSA suits are being filed. Without such an understanding, the scope of the problem may seem too daunting to tackle. Not every FLSA issue poses the same risk of litigation. Understanding which FLSA violations are more likely to result in a lawsuit can help us to distinguish matters that need to be addressed sooner rather than later.

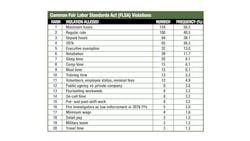

This Fire Law article focuses on the five most common reasons that fire departments are being sued under the FLSA based on my fire litigation database, which, at the time of analysis, included 247 FLSA cases. Most of the cases contain several allegations of FLSA violations. For example, a suit may allege a regular-rate violation, a maximum-hours violation as well as a claim for unpaid hours. Relatively few FLSA suits allege only a single FLSA violation.The data in the table (above) represent the 20 most common FLSA violations that are alleged in lawsuits, the number of allegations and the relative frequency (percentage) for each violation. For purposes of discussion, we will focus on the top five.

Maximum-hours violations

In my database, the most common FLSA violation that is alleged is what is referred to as a maximum-hours violation. Such suits are brought by firefighters who claim that they are working hours that are in excess of the statutory maximum without being paid overtime. The statutory maximum for most employees is 40 hours in a seven-day workweek. The FLSA allows a partial exemption for firefighters and law-enforcement personnel, which is known as the 207k exemption. Qualifying firefighters are allowed to work up to 53 hours per week, or up to 212 hours in a 28-day work period, before overtime is required.

Maximum-hours violations are alleged in just over half of the FLSA lawsuits filed to date in my database. In some cases, suits are brought by officers who claim that they were wrongly classified as being exempt from overtime. In the remainder, employees allege that their employer wrongfully failed to pay them overtime when they were entitled to it.

Regular-rate violations

Regular-rate violations are alleged in two out of every five FLSA suits in my database. Unlike maximum-hours violations, regular-rate violations arise when firefighters are paid overtime for the extra hours that they work, but the rate that was paid is less than what the FLSA requires.

Regular rate is a complex topic, but at its core is a simple concept: When employees who are entitled to overtime (referred to as nonexempt employees) work more than the statutory maximum, they must be paid one-and-one-half times their regular rate. Regular rate is not just an employee’s normal hourly wage. Regular rate must include consideration of all of the various forms of compensation that the employee receives, such as longevity pay, educational incentives, specialty pay, shift differentials and acting out of rank (step-up) pay, to name a few.

The proper calculation of regular rate is fertile ground for debate even among experienced FLSA attorneys. The problem is compounded by employees who are paid a salary that must be converted into an hourly wage, to which the additional types of compensation must then be added. Suffice it to say, regular-rate cases will continue to be filed, and regular-rate calculations should be an area of focus for fire department leaders who hope to avoid a visit to federal court.

Unpaid hours

Unpaid-hours cases allege that firefighters were not compensated for certain work that they performed. This includes firefighters who claim that they were not paid for certain training activities or for attending certain meetings; officers who claim that they were wrongly categorized as exempt and not compensated for the additional hours that they worked; firefighters who were on-call but believe that the requirements for being on-call were so burdensome as to require full compensation; and what we commonly refer to as off-the-clock work.

Off-the-clock work refers to time that was worked outside of one’s normal hours. When the FLSA was originally enacted in 1938, off-the-clock work referred to people who came in early or stayed late. The digital age has created a new category of off-the-clock work for those who use technology to work on things, such as fire reports online from home as well as sending and receiving work-related emails after hours.

207k violations

The 29 USC 207k section of the FLSA creates a partial-exemption from the 40-hour requirement for qualifying firefighters and law-enforcement personnel. To qualify for the 207k exemption, firefighters must meet the definition of an employee engaged in fire protection activities. Qualifying personnel can work up to 53 hours per week, or up to 212 hours in a 28-day work period, before overtime is required.

Lawsuits that allege a violation of 207k claim that employees were wrongly categorized as qualifying as an employee engaged in fire protection activities. Cases in my database include suits by EMS personnel, dispatchers, mechanics and even firefighters who are assigned to non-207k qualifying positions.

Executive exemption

Roughly 13 percent of FLSA cases are brought by officers who claim that they should not be classified as exempt employees (exempt meaning not entitled to overtime). Over the years, cases have run the gamut from lieutenants who were found to be exempt executives to deputy chiefs who were found to be nonexempt.

The cases became so conflicted that in 2004 the Labor Department issued new regulations that are intended to better define who is exempt and who is not. Those regulations, which are commonly referred to as the First Responder Regulations, clarified that “fire fighters, paramedics, emergency medical technicians, ambulance personnel, rescue workers, hazardous materials workers and similar employees, regardless of rank or pay level, who perform work such as preventing, controlling or extinguishing fires of any type; rescuing fire, crime or accident victims” are to be considered nonexempt.

Despite that relatively clear mandate, courts have muddied the waters with inconsistent interpretations of the regulations. In one case, a U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rendered a decision that upheld a jury verdict that lieutenants who are assigned to fire companies are exempt executives. Inexplicably, the court did not even mention the First Responder Regulations. Most courts have ruled in the opposite direction with regard to company officers, finding them to be nonexempt and, thus, entitled to overtime. The result is that the intent of the Labor Department to provide more clarity and less litigation over this issue has, in large measure, been frustrated.

The biggest battleground today is over the status of line chiefs as exempt executives or nonexempt hourly employees. Line chiefs appear to meet the requirements of the First Responder Regulations, because their primary duty is to respond to fires and emergencies. However, they have greater management responsibility compared with company officers, which raises a question about whether their primary duty is management of the enterprise.

Given what is at stake, the executive exemption is another problem area that will not be going away any time soon.

Avoiding litigation

The FLSA is one of the most likely ways that a fire department will be sued. Whether career, combination or volunteer, the FLSA poses a risk. Given that most career fire departments rely on overtime to meet minimum staffing requirements, and that volunteer and combination departments struggle to recruit and retain members, the risks that are associated with the FLSA are likely to continue into the foreseeable future. By understanding the most commonly cited allegations in FLSA lawsuits, fire service leaders can better focus their efforts to avoid unnecessary litigation.

Curt Varone will present “Liability Trends & Traps: Hot Topics in 2020” at Firehouse World. To register, visit FirehouseWorld.com.

Curt Varone

CURT VARONE has more than 40 years of experience in the fire service, including 29 years as a career firefighter with Providence, RI, retiring as a deputy assistant chief (shift commander). He is a practicing attorney who is licensed in Maine and Rhode Island and served as the director of the Public Fire Protection Division at the NFPA. Varone holds a master's degree in forensic psychology from Arizona Statue University. He is the author of two books, "Legal Considerations for Fire and Emergency Services" and "Fire Officer's Legal Handbook," and remains active as a deputy chief in Exeter, RI.