When firefighters think of liability, they often focus on incident-related liability, and for good reason. We are engaged in a dangerous profession where people are killed and injured and their property is damaged or destroyed, even when we did everything humanly possible to intervene.

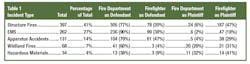

Although the statistics tell us that fire departments and firefighters are more likely to be sued over personnel matters, incident-related lawsuits are a major concern. For that reason, it is worth understanding the types of incidents that are most likely to lead to lawsuits.Table 1 lists the five most common types of incidents that lead to civil lawsuits, along with a breakdown of who is suing who. The statistics are drawn from my fire litigation database. At the time of the analysis, there were 9,879 cases in the database, of which 3,921 were civil suits and 962 were incident related.

The most likely reason for an incident-related lawsuit is a structure fire. This accounts for 397 suits (41 percent) of the 962 cases. That may seem surprising given that structure fires account for less than 1 percent of a typical fire department’s responses.

Of the structure fire suits, the most likely party to be sued is the fire department, which accounts for 305 cases (77 percent). In 92 cases (23 percent), the property owner was sued, most commonly by a firefighter who was injured. Firefighters were named as defendants in 78 cases, or roughly 20 percent of the time.

Surprisingly, firefighters filed 187 of the 397 structure fire suits (47 percent). Although their favorite target was the fire department (117 of 187, or 63 percent), they also sued property owners and others who they believed were responsible for injuries that they sustained, including contractors who caused fires and PPE manufacturers.

The second most likely incident to lead to litigation is an EMS response, which accounts for 27 percent of suits. Of the 262 EMS lawsuits, the fire department was named as a defendant in 236, or 90 percent of the time. Firefighters were named personally in 99 cases (38 percent), including 87 cases that named both the fire department and a firefighter.

Ranked third comes apparatus accidents, which account for 131 lawsuits (14 percent). Fire departments were the most likely target of apparatus accident suits, which account for 104 cases (79 percent), followed by firefighters (61 cases, or 47 percent). In 55 cases, both departments and firefighters were sued (42 percent). Fire departments sued the other driver in just five cases (4 percent), while firefighters sued in 38 cases (29 percent).

The fourth category is wildland fires, which accounts for 68 suits (7 percent). Fire departments were named as a defendant in 41 cases (60 percent). Firefighters were named in just three wildland suits. In 31 percent of wildland cases, firefighters were the ones who sued, while the fire department sued in 29 percent of the cases. All of the suits that were brought by firefighters were for injuries that were sustained in battling the fires, while the suits that were brought by fire departments were for cost recovery.

The final category, hazardous materials incidents, represents just 4 percent of the incident-related suits. Unlike the other categories, fire departments were not the most likely target of hazmat suits. Rather, property owners and third parties were named in 24 of 34 suits (71 percent), which makes them the most likely target. Firefighters brought 14 of the suits, and fire departments brought 11, for a total of 25 suits, or 74 percent of the suits that were filed.Legal theories

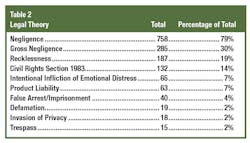

Table 2 shows the most common allegations that were made in incident-related lawsuits. By far, the most common allegation is negligence, which was alleged in 758 of the 962 cases (79 percent). The second most common allegation is gross negligence (285), which is followed by recklessness (187).

The fourth most common allegation may very well be the most interesting: civil rights violations. Most municipal fire departments enjoy some degree of immunity from liability for negligence. However, as governmental agencies, fire departments must respect the constitutional rights of everyone. Tort immunity does not shield a fire department from suit for civil rights violations. Attorneys use such claims to circumvent tort immunity. That is why 132 incident-related suits (14 percent) include allegations of civil rights violations. The most common civil rights violation that was alleged is for a denial of due process that is based upon a deprivation of life or property due to a governmental actor’s “deliberate indifference,” which accounts for 129 of the 132 cases.

The next most common allegation is intentional infliction of emotional distress, which accounts for 7 percent (65 cases). The remaining five categories are product liability (7 percent), false arrest (4 percent), defamation (2 percent), invasion of privacy (2 percent) and trespassing (2 percent).

Managing the liability

The five most common types of incident-related suits (structure fires, EMS, apparatus accidents, wildland fires and hazmat) account for 892 of 962 incident-related suits (93 percent), with structure fires being the most common. The remaining categories include crashes that involve personally owned vehicles, confined-space rescue, dive rescue, rope rescue, ice rescue, water rescue, structural collapse, false alarms, gas leaks, vehicle fires, ship fires and trash fires, with none exceeding 1 percent of the total. Therefore, to effectively manage incident-related liability, a focus should be on the top five, and particularly the top three.

The most common legal theory that is alleged in incident-related cases is negligence, which accounts for 79 percent of the cases. In 14 percent of the cases, attorneys alleged civil rights violations in an effort to circumvent immunity protection that otherwise might shield a fire department from liability. Our best defense against both theories are effective policies, training and supervision.

Curt Varone

CURT VARONE has more than 40 years of experience in the fire service, including 29 years as a career firefighter with Providence, RI, retiring as a deputy assistant chief (shift commander). He is a practicing attorney who is licensed in Maine and Rhode Island and served as the director of the Public Fire Protection Division at the NFPA. Varone holds a master's degree in forensic psychology from Arizona Statue University. He is the author of two books, "Legal Considerations for Fire and Emergency Services" and "Fire Officer's Legal Handbook," and remains active as a deputy chief in Exeter, RI.