FDNY, Twin Towers and Organizational Change

Organizational change requires energy. People must feel a need, either to stop doing something that they are doing or to start doing something that they aren’t doing. Organizational trauma can create such a need, but utilizing that felt need for change falls to leadership. For example, a traumatized organization can turn inward or look outward.

The tragedy of the Twin Towers led FDNY not to cover up but, quite the contrary, to turn outward and, so, to change.

Prior to the events of 9/11, FDNY qualified as a uniquely insular department. It possessed enough equipment and personnel to never need outside support. Firefighters and higher-ups came from around the world to learn how FDNY operated. Rarely, if ever, did FDNY venture out to learn from others. FDNY taught itself, learned its lessons internally, and created tactics and procedures from its experiences from within the city’s boundaries.

By the fall of 2001, all senior leaders had gained tremendous firefighting experience during the “War Years” of the ’60s and ’70s. Simply put, they knew how to fight fire and didn’t feel the need to look outward for help. This insularity led former FDNY Commissioner Sal Cassano to declare that the department had “150 years of tradition unimpeded by progress.”

The collapse of the World Trade Center killed 343 FDNY firefighters, including many of its senior leaders, and destroyed hundreds of firefighting vehicles. Convulsed, FDNY could have turned inward, took its own counsel and treated the events of 9/11 as a black swan, one never to occur again. It could have defined renewal as rebuilding of what existed on 9/10. Instead, FDNY allowed outsiders in, accepting their help, and began its own passage to becoming a more open and learning organization.

The staggering work of rescue and recovery that followed the collapse of the World Trade Center opened the department’s eyes to the greater world of emergency management. Several events help to delineate the stages of change in insularity from before 9/11, to FDNY’s transition, to how the FDNY emerged, renewed and altered.

Before 9/11

A senior firefighter, who also was a member of a suburban volunteer fire department, wanted to attend a course at the National Fire Academy. He believed that the course would be extremely useful for his role as an FDNY battalion chief. He approached a staff level chief for approval to attend the course.

The staff chief asked, “We can send people there?”

The battalion chief explained further.

Upon hearing that there would be no cost to FDNY for the course or lodging, the staff chief was incredulous. “Okay, I’ll let you go, but if any of this is BS, there will be repercussions.”

Transition

FDNY Deputy Commissioner Tom Fitzpatrick related that on Sept. 11, 2001, he was in contact with federal counterparts at FEMA. They indicated that the scale of the incident called for deployment of multiple all-hazards incident management teams (IMTs).

“I was very nervous allowing an outside agency into an FDNY operation,” Fitzpatrick said. “As far as I know, it had never happened before.”

The FEMA officials convinced him that this was the right call.

FDNY Chief Peter Hayden offered these comments about the arrival of the Forest Service, aka the Tree People, in the days after the collapse, in full forest ranger regalia: “Here’s a guy from the Grand Canyon. I said, ‘I’m in the canyons of New York. How is this guy going to help me?’ … They relieved me of so [many] other problems … The impact that they had on the ability of the chief officer … the IMT helping the incident commander and managing an emergency.”

After

The interaction and assistance of the IMTs in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks proved successful. As a result, FDNY jumped at future opportunities to train within the National Incident Management System (NIMS). NIMS principles and terminology were integrated into FDNY protocols.

In 2005, federal funding for local preparedness grants became conditional on NIMS compliance. FDNY had a four-year head start. In fact, FDNY became a trusted partner of NIMS, aiding in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and, in 2021, taking over incident command of a Montana wildfire from a beleaguered forestry service.

Work Systems Model

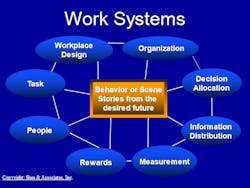

During transition, organizational leaders help to determine, as above, how not just to lead through a moment but to seize it. Seizing it can, in turn, entailThe formal process of employing the WSM involves:

- Identify what you want to create (stories from the future)

- Given that eight aspects of the organizational environment that drive behavior (workplace, task, people, rewards, measurement, information distribution, decision-allocation and organization) can drive other behavior, convert at least four of the eight aspects into levers of change

- Continue to refine the stories and your pulling of the levers

- Alter patterns of behavior (which, by definition, means that organization culture has changed) by embedding structural changes

Table 1 presents how FDNY ended up, in effect, employing the model.

Changing culture

Organizational trauma calls for individual and organizational resilience. It also creates an occasion for change, as the collapse of the World Trade Center did for FDNY. Departmental leadership didn’t merely rebuild the department; they remade it. This included converting it from insular to outward-looking. Leadership did so by systematically and persistently changing the determinants of departmental behavior and, thereby, in effect, changing its culture.

The Eight Levers of the Work Systems Model

1) Workplace: Layout of physical and virtual space; available work tools and technology

- Incident management teams (IMTs) with dedicated space and use common FDNY radio

- Partnering with climbing equipment company Petzl to develop the Personal Safety System

2) Task: Work processes, protocols and practices, including timelines

- Approval of travel no longer required the mayor: easier to go places and to learn

3) People: Selection, training, development of talent (e.g., task competency and process skills, such as stakeholder mapping as well as key stakeholder ties, and training in group processes, including conflict management and evolving team membership and roles, including leadership

- Selection of IMT personnel based on skill sets that are outside of those that normally are used to select personnel for structural firefighting (e.g., accounting, computer-related, restaurant and catering, supply logistics and transportation)

- Training facilities, integrated IMT training (within and outside FDNY)

- Open training to “outsiders” (e.g., the U.S. Coast Guard) and, thereby, facilitate cross-fertilization

- Partner with outside organizations (e.g., Columbia University, Naval Postgraduate School, U.S. Military Academy West Point, Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania)

- NIMS and Guardians Center training (private and military) as well as ship fire training at FDNY Randall’s Island simulator (includes Coast Guard personnel)

- Training with NYPD, OEMs, hospitals (e.g., simulations), New York City Transit, Metropolitan Transportation Authority and ConEd

4) Rewards: Rewards and punishments of any sort (intrinsic and extrinsic), including experienced success, recognition, financial incentives, skill development, promotion and future assignments

- Full compensation plus overtime pay for outside IMT that work within and outside New York City

- Opportunity for advancement: IMT hierarchy not based on FDNY rank but on training and competency

- Value of NIMS

- Exposure to senior officers as part of IMT activities

5) Measurement: Outcome and process metrics or scorecards

- Adequacy of staffing (i.e., three deep at each IMT position)

- Member certifications

6) Information Distribution: Ease and comprehensiveness of access to information (external): Who gets to know what, when and how easily (pulled or pushed)?

- Grants, IMTs and people from all over at incidents; openness of cross-organizational exchanges (within and outside of New York City)

- Free flowing information within IMTs (e.g., after each incident, morning briefings and daily incident action plan)

- Day Challenge for local businesses to learn from FDNY about leadership, problem-solving, decision-making and team-building

7) Decision-allocation: Who participates when and in what way in which decisions? In responsibility or RACI charting terms, nature and clarity of decision-making steps and both individual and group roles in each of them

- IMT “founding” principle regarding collaboration under return on equity, namely IMT manages the IMT, not the incident (i.e., necessary resources, run by agency administrator)

8) Organization: Overall vertical and horizontal organizational structure (e.g., organization chart), such as geographic, functional or matrixed as well as task forces, project teams and committees or other regular meeting groups

- Creation of separate and independent IMT and Center for Terrorism and Disaster Preparedness

- Re-establish borough commands, with authority to act as independent entity as needed, hence, the need to develop the capacity to act independently

Source: “Leading Successful Change: 8 Keys to Making Change work,” G. Shea & C. Solomon, Wharton School Press, 2020.

About the Author

Gregory P. Shea

Gregory P. Shea, Ph.D., consults, teaches, researches and writes in the areas of organizational and individual change, leadership and its development, innovation, and group effectiveness. He has worked with senior leadership, including boards of directors, as well as deep within organizations. Shea is a senior fellow at the Wharton School’s Center for Leadership and Change, an adjunct professor of management at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and of its Aresty Institute of Executive Education, an adjunct senior fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the Wharton School and president of Shea & Associates. His awards include an Excellence in Teaching Award from Wharton. Shea is a member of the Academy of Management and the American Psychological Association.

Paul Brown

Paul Brown is an educator, leadership coach and retired New York City Fire captain. A third-generation firefighter, he spent more than 30 years as a first responder. As part of the FDNY Incident Management Team, Brown deployed to natural disasters and wildfires throughout the United States. A graduate of John Jay College, he has been involved in experiential education and executive leadership coaching for the 20 years.