When the calendar hits December, most of the country starts celebrating. December brings Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanza and New Year's Eve! But, for firefighters, December brings back memories of some of the worst tragedies in fire service history. Whether it was dealing with the unimaginable loss of elementary school or high school students or the heartbreak of losing several members of your own crew, December can be, as one firefighter put it, "a very cruel month."

Dec. 1, 1958, Chicago—Our Lady of the Angels School Fire

It was about 20 minutes before the end of classes on Dec. 1, 1958, at Our Lady of the Angels School on Chicago’s West Side. The Main Fire Alarm Office in City Hall received a telephone call at 2:42 p.m. from the housekeeper in the church rectory on West Iowa Street reporting a fire. Unfortunately, the housekeeper gave the address of the rectory and not the heavily overcrowded brick school around the corner, a fact that ultimately had a significant impact on the response.

As Alex Burkholder so brilliantly described in his 2018 Firehouse article, “60 Years Later: Our Lady of Angels School Fire,” first responders responded to the rectory, only to see children jumping out of second-story windows of the south wing of the school. Hysterical parents and students told the firefighters that the blaze was centered in the north wing around the corner on North Ayers Avenue.

As Burkholder reported, “The fire had started in the basement and quickly spread up a stairwell. Fire doors on the first floor stopped the smoke and flames, and students on that floor fled the building. Things were much different on the second floor where there were no fire doors and the smoke and flames spread down a hallway, trapping students in five classrooms. The students’ only way out was through the windows. Ironically, a fire department inspector at the school a couple of months before the fire had noted the lack of fire doors upstairs, but because of the building codes and grandfather clauses, he could not demand their installation.

“At 2:57 p.m., 15 minutes since the first alarm, a section of roof collapsed. The fire was raised to a 5-11 alarm. But any chance of finding survivors was gone.

“The death toll from those five rooms was 95 of which 92 were students and three were nuns. Fifty-six of the dead students were girls and 36 were boys.

“As a result of the tragic fire, all schools in Chicago would have fire alarm boxes that could be pulled outside of the schools and were also connected to alarm devices in their interiors. In addition to other safety improvements—fire doors, use of non-flammable materials and getting rid of transoms over doors—many Chicago schools were required to install sprinkler systems. As a precaution, while improvements were being made, firefighters were assigned to patrol public and parochial schools during class hours.”

Dec. 2, 2016, Oakland, CA—Ghost Ship Fire

At approximately 11:20 p.m. on Dec. 2, 2016, a fire ignited at a converted warehouse, known as Ghost Ship, at 31st Avenue near International Boulevard in Oakland, CA. The fire ultimately killed 36 individuals, making it the deadliest fire in Oakland’s history and the country’s deadliest building fire since the Station Nightclub fire in West Warwick, RI, in 2003.

In February of 2017, Firehouse provided a Progress Report on the incident.

“ATF investigators indicated that the fire started on the first floor and quickly spread through the two-story, 10,000-square-foot live-work space, which was home to an artist collective and hosting a concert the night of the blaze. The warehouse was described by many as being cluttered with furniture, pianos, artwork, wood pallets and wiring. There were two stairways, but neither led to an exit. Oakland Fire Department (OFD) Fire Chief Teresa Deloach Reed said it was ‘like a maze.’ What’s more: There were no fire sprinklers, and firefighters later indicated that they did not hear any smoke detectors.”

One year later, Battalion Chief James Bowron shared “Lessons from the Ghost Ship Fire,” with attendees at Firehouse World.

"As I was doing my 360, what I could see was that the only access into this building was a man-made door that was cut out of a commercial roll-up. And it's not like it was a clean door that was welded up all nice and neat,” Bowron told the crowd.

"When I talked to the engine companies, they were only able to get about 15 or 20 feet through the door and were already getting smoke conditions that were terrible. They were running into pianos and having a hard time trying to make their way in."

It was then that Bowron went with the very difficult decision to not make an announcement to his crews over the radio that there were 50 to 75 people reported to be inside.

"Had I made that announcement that there might have been 50, 60, 70 people in there, my crews—which had already pushed and pushed and pushed as hard as they could— would have probably made decisions or pushed themselves to a further limit which may have caused potential loss of life for the fire department on our end."

It's an operational decision Bowron says he understands some might question, but he remained steadfast that he did the right thing.

In a 2019 Ghost Ship trial, jurors acquitted one man blamed for dangerous conditions in the warehouse where 36 people died in a horrific fire and deadlocked over the responsibility of another.

Dec. 3, 1999, Worcester, MA—Worcester Cold Storage Warehouse Fire

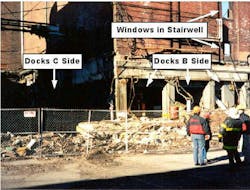

On Dec. 3, 1999, at 6:13 p.m., a fire was reported by an off-duty police officer in the vacant Worcester Cold Storage and Warehouse at 266 Franklin St. The initial response was Worcester Fire Department (WFD) Engines 1, 6, 12 and 13, Ladders 1 and 5, Rescue 1 and Car 3. The building was known to be abandoned for over 10 years.

On the 10th anniversary of this tragic day, Christopher J. Naum authored “The Worcester Six + Ten: Remembrance 1999-2009” for Firehouse.

Naum reported “Eleven minutes into the fire, the owner of the abutting Kenmore Diner advised fire operations of two homeless people who might be living in the warehouse. The rescue company, having divided into two crews, started a building search. Some 22 minutes later the rescue crew searching down from the roof became lost in the vast dark spaces of the fifth floor. They were running low on air and called for help. Interior conditions were deteriorating rapidly despite efforts to extinguish the blaze, and visibility was nearly lost on the upper floors.

“Investigators have placed these two firefighters over 150 feet from the only available exit.

“An extensive search was conducted by Worcester Fire crews through the third and fourth alarms. Suppression efforts continued to be ineffective against huge volumes of petroleum based materials, and ultimately two more crews became disoriented on the upper floors and were unable to escape. When the evacuation order was given one hour and forty-five minutes into the event, five firefighters and one officer were missing. None survived.”

For the next eight days, crews worked around the clock to locate the bodies of the six firefighters who were lost. They are:

- Paul Brotherton

- Tim Jackson

- Jeremiah (Jerry) Lucey

- Lt. James (Jay) Lyons

- Joseph McGuirk

- Lt. Thomas (Tom) Spencer

In his “The Worcester Cold Storage and Warehouse Fire: 20 Years Later” article for Firehouse, Gus Maynard reported on the 13 NIOSH recommendations following their investigation and how the Worcester Fire Department responded to those recommendations.

Interview with retired Worcester District Chief Mike McNamee. As the 10th anniversary of the deadly Worcester Cold Storage warehouse fire approached, he recalled that tragic night.

Firehouse has had extensive coverage of the Worcester tragedy over the years including:

Denis Leary’s “Reflections on Worcester.”

Joe Vince’s report on several sons of firefighters lost that day continuing their fathers’ legacy.

A slideshow of Scott LaPrade’s on-scene photos from that day.

An interview with Worcester District Fire Chief Walter Giard who talked about how the department approached training afterwards.

Firehouse.com News Editor Susan Nicol’s article on the NIOSH and U.S. Fire Administration reports on the incident.

Dec. 7, 1946, Atlanta—Winecoff Hotel Fire

It is believed that some 280 guest occupied the Winecoff Hotel on Dec. 6, 1946, including a large number of teenagers from across the state of Georgia; in town to attend the annual Youth Assembly at the Georgia State Capital which was being sponsored by the YMCA.

According to Timoth Syzmanski's “The Winecoff Fire—Our Nation’s Deadliest Hotel Fire,” “at 3:42 A.M. a telephone alarm was received at fire headquarters reporting a fire at the Winecoff Hotel. No. 8's Engine and Ladder, along with 4's, 1's and 3's engines, and 4's and 1's ladder, Rescue, and the Light Truck were dispatched to Peachtree and Ellis streets. Along with the first alarm, Second Assistant Chief F. J. Bowen, and Chief of Department Charles C. Styron, Sr., responded.

“Upon No. 8's arrival at the Winecoff, having arrived there within two minutes of receiving the alarm, the firefighters discovered dense smoke and flames emitting from the third, fourth and fifth floors! To compound this sight, the horrifying sound of voices of trapped occupants could be heard echoing from the thick smoke high above historic Peachtree Street. Chief Styron ordered his men to begin an immediate rescue effort with the aerial-ladders, while an interior attack was deployed utilizing the interior stairway to advance hoselines. Much to the horror of the firefighters, bodies began to appear through the thick smoke from above, and violently plummeted to the sidewalk on Peachtree Street...jumpers!

“Simultaneously, a second and third alarm was sounded by Chief Styron at 3: 44 A.M., summoning additional engines and ladders. As the magnitude of this event continued to reveal itself, a fourth alarm was sounded at 3:49 A.M., followed by a general alarm at 4:02 A.M.; summoning all of Atlanta's equipment, as well as the entirety of all off-duty personnel.”

In “The Winecoff Fire—50 Years Later,” Dave E. Williams described what the firefighters were dealing with at this hotel.

“The structure occupies a plot 63 feet by 70 feet at grade, with the main entrance and marquee on Peachtree Street. It was 15 stories (about 155 feet) with a full basement and a small sub-basement. The floors were numbered from one to 16 but, as is the case in many hotels, there was no 13th floor. It had been omitted from the numbering system out of deference to superstition. The top floor was known as the 16th.

“The construction classified at the time as ‘fireproof’ included protected steel frame with the roof and floors of concrete on tile filler between protected steel beams and girders. Dividing walls between rooms were of hollow clay tile, plastered on both sides. Exterior walls were 12-inch brick panel type. Doorways typical of the times had "transom" windows over each to assist in ventilation in a hotel prior to air conditioning. These open transoms would spell disaster this night.

“Of the 280 guests and employees in the hotel, 119 were killed and over 100 injured. The fatalities included some of Georgia's most promising high school students who had come to Atlanta for a YMCA Youth Assembly to be held at the Georgia Capitol on Dec. 7. Also among the dead was W.F. Winecoff, the hotel's original owner, who lived in the building. He lost his life in his room within the "fireproof" hotel that bore his name.”

Dec. 21, 1910, Philadelphia—Philadelphia Leather Factory Fire

On Dec. 21, 1910, Philadelphia firefighters rolled out to a reported fire at 1114 North Bodine St., a five-story leather factory. Heavy fire was found on the first floor upon arrival and a second alarm was transmitted immediately. For almost three hours, the battle continued when without warning, a major collapse occurred, trapping 36 firefighters in the flaming debris.

Paul Hashagen provided details in his “December 1910: A Tragic Month for the Fire Service,” feature for Firehouse.

“A number of men were rescued from the collapse area and rushed to hospitals. The heroic rescue operations continued for two hours until a second collapse occurred, bringing the number trapped to 51. The rescue effort was renewed.

“The last live firefighter, William Glazier of Engine 6, was freed from underneath a heavy beam and some machinery after a 12-hour rescue operation. Despite freezing temperatures, firefighters cut, lifted and moved the charred remains of the factory until the last of their brothers was recovered.

In all, 13 firefighters and one police officer were killed, and more than 50 men were injured, many seriously.”

Dec. 22, 1910, Chicago—Stockyard Cold Storage Fire

Just after 4 a.m. on Dec. 10, fire broke outin the basement of the Nelson Morris & Co. meatpacking plant in the Union Stockyards in Chicago.

Paul Hashagen provided details in his “December 1910: A Tragic Month for the Fire Service,” feature for Firehouse.

“The interior walls of the structure were wooden and soaked with years of animal fat and grease, and tons of stored meat was covered with saltpeter, one of the main ingredients in gunpowder. Outside, things were also taking a turn for the worse when firefighters discovered nearby fire hydrants had been shut off to prevent freezing. By the time a water source was secured, the building was fully involved. A number of physical obstacles also hampered the firemen's efforts as nearby railway cars, brick walls and other structures closely surrounded the blazing building.

“Chief James Horan was directing a group of firefighters who had stretched lines over a railcar and were operating from a loading dock when an explosion rocked the building, toppling a six-story wall across the loading dock and killing the chief, Assistant Chief William Burroughs, three captains, four lieutenants and 12 firefighters.

“Additional alarms and special calls were sent in bringing the total number of units to 50 engine companies and seven hook-and-ladders at the scene. The fire and rescue operation continued for more than 24 hours until the fire was finally declared under control at 6:37 a.m. on Dec. 23.”

Other Notable December Fires

Dec. 2, 1913, Boston—Arcadia Hotel Fire

Dec. 5, 1876, Brooklyn, NY—Brooklyn Theater Fire

Dec. 16, 1835, New York—Great New York Fire

Dec. 30, 1903, Chicago—Iroquois Theater Fire