Health & Wellness: Firefighter Peer Support

The breadth and depth of challenges faced by the fire service is significant. Among these struggles are cancer risks, budget constraints, vehicle maintenance, overtime costs and a laundry list of other concerns. Another looming and often undiscussed problem is providing for firefighter behavioral health. The scope of this problem, its challenges and what can be done to remedy those challenges must be considered if we are to provide behavioral health services to our brothers and sisters.

Higher rates of suffering

To understand the scope of firefighter behavioral health problems, let’s examine some statistics. According to the National Association of Mental Illness, in the general U.S. population, approximately 20 percent of people will suffer from a mental health condition annually.1 Now, let’s isolate and consider the impact of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on the fire service by itself. It is estimated that up to 22 percent of firefighters suffer from PTSD.2 The astounding realization when we compare these statistics is that firefighters suffer from PTSD at a higher rate than the general population suffers from all mental illnesses combined. If we then factor in all possible behavioral health disorders, it is clear that firefighters suffer from these disorders at a rate far exceeding the general population.

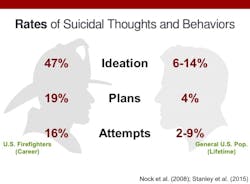

Let’s look at another devastating aspect of behavioral health—suicide. Researchers recently gathered new information about fire service suicide, and the results are sobering. In one survey of over 1,000 active and retired firefighters, nearly half of respondents stated that they had considered suicide, which is over three times the rate of the general population.3 Additionally, 16 percent had actually attempted suicide, as compared to 2–9 percent of the general population.3

Again, when we compare firefighters to the general population, it becomes evident that firefighters have a greater need for services than has traditionally been recognized or admitted. Because of this, it is essential that we develop methods to discover behavioral health problems and to get our brothers and sisters into to effective treatment programs. This is where the challenges begin.

Barriers to help

Unfortunately, getting firefighters help is difficult. The foremost challenge is overcoming those who stigmatize behavioral healthcare. In a recent study, 92 percent of firefighters surveyed stated that they would not seek behavioral health care because of the associated stigma.4

“Telephone, telegraph, tell a firefighter” is an adage with which we are all familiar on some level, and when it comes to being labeled, many firefighters fear having sensitive information spread throughout the department. And unfortunately, while the “toughen up, kid” mentality is a large hurdle, it is by no means the only obstacle to success.

Firefighters are a family. The bonds we have with our brothers and sisters are essential to the work we do. As part of that, firefighters may fear that getting someone help will “jam them up” or cause administrative repercussions. As a result, firefighters often try to deal with problems “in house.”

And please don’t misunderstand; there can be value in that approach, if you are legitimately assisting your brother or sister. Unfortunately, that type of assistance is too often just an attempt to put the problem to bed and cover up for our brothers and sisters. Ultimately, these efforts to “assist” are little more than repeated episodes of enabling, which never resolve the underlying problem—and probably make it worse. In this context, enabling is a “process where a person unwittingly aids a person’s negative behavior.”5

The detrimental results of covering for our brothers and sisters make clear that seeking outside assistance is often the best answer, but in our closed environment, outsiders are rarely trusted. We will examine how to overcome this distrust later, but for now, it is sufficient to recognize that this issue represents a significant challenge to getting our people professional help.

Another significant obstacle in firefighter behavioral health relates to privacy and employee assistance programs. NFPA 1500: Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety (Chapter 11) provides recommendations for establishing Behavioral Health and Wellness Programs. One of Chapter 11’s mandates is that fire departments establish employee assistance programs (EAPs) for members and their families.

While EAPs work well in many areas, they are consistently distrusted by firefighters. Because of the connection between the EAP and the administration, firefighters are often concerned that sensitive information will be relayed back to headquarters. Unfortunately, disclosures of information, whether accidental or deliberate, have occurred, and it is those rare examples that firefighters will seize upon when refusing to visit an EAP.

It is incumbent upon peer support teams to educate firefighters about EAPs and how confidentiality works. By doing so, peer support members can point out that those disclosures are the exception rather than the rule, and should not be used to avoid getting treatment. Privacy, however, is not the only issue that raises concerns with EAPs.

Cost considerations are a reality for most municipalities. EAPs that win government contracts are often the low-bid offer, which, while helpful to the municipality’s bottom line, does not foster a sense of trust among already skeptical firefighters. When confronted with a low-bid EAP, firefighters question whether the counselors are inexperienced or poor performers. They also harbor concerns about the reliability of the service. While these issues with EAPs are not insurmountable, we must be cognizant of attitudes towards EAPs if we hope to find solutions.

Peer support helps

What, then, can be done to remedy these challenges? Perhaps the greatest resource that departments can develop and promote is peer support teams. The peer support model engages firefighters in five areas that make it effective for getting firefighters behavioral health assistance:

1. Peer support teams conduct “routine visits.”

2. Because peers are firefighters, they are more likely to be requested than an outsider when assistance is needed.

3. Peer support teams can more easily visit crews after traumatic events and be welcomed into the firehouse to do so.

4. Peer support members engage other firefighters through a variety of educational efforts.

5. Peer support teams can develop and vet resources that firefighters can trust.

Central to these five areas of engagement is the idea that some areas are proactive and others are reactive. The peer support model utilizes proactive engagement via routine visits, education and resource development to set our members up for success. For those inevitable occasions where something bad does happen, it assists reactively through requested visits and responses after potentially traumatic events. Let’s look at each of these five engagement methods individually for better understanding.

Routine visits

In a routine visit, a peer support member will call the firehouse and request permission to stop by for a brief visit. During this visit, the peer support member introduces the peer support program, who its members are, and what the program does. This serves several purposes. First, it lets firefighters know that the program is available and that it is not affiliated with the EAP. Next, it allows firefighters to put a face to the program, which is crucial for firefighters to see that team members are “one of them.” It is also useful for normalizing discussions about mental health and educating firefighters that needing assistance is not a sign of weakness. Peer support teams “can also help normalize mental health by … comparing good mental health with physical health.”6 This type of engagement goes a long way toward stigma reduction, which is a leading obstacle to seeking assistance.

Requested visits

The second engagement method is the “requested visit.” When help is sought for a problem in the firehouse or in someone’s personal life, there is an instinct to reach out to someone who understands firefighters and who can be trusted. Under the peer support model, the firefighter has a team of other dedicated firefighters waiting to assist. And by the very nature of our bonds as firefighters, peer support members are deemed more trustworthy than outsiders. Being able to talk one-on-one with another firefighter who understands this lifestyle, who isn’t going to judge you, and who cares about you on a familial level is the genius behind the peer support model. This type of visit also allows the firefighter and peer to discuss treatment options and develop an action plan that can be implemented and adjusted until the situation is resolved. When the firefighter knows that he is not going to have to go through this experience alone, he is more likely to ask for help.

Traumatic events

When people think of peer support, they probably also think about the need for services after a particularly bad call. Certain calls are expected to arouse a strong emotional response in firefighters. Examples of these calls include child fatalities, maydays, mass casualties, terrorist acts, member suicides and line-of-duty deaths.

The peer support model differs from some other models in that it does not engage in centralized group debriefings after a traumatic event. Under the peer support model, peer support members visit the fire stations involved in the incident, check in with firefighters individually to discuss coping and what to expect emotionally, and provide a chance to speak privately if the firefighter wants it. Team members also leave contact information for firefighters who want to talk after the team has left.

The benefit of using this method is that firefighters do not have to leave the comfort of their station to get the necessary information. This makes the dissemination of information convenient for the firefighter, decreases hostility toward the behavioral health team, and causes the least amount of disruption, while still providing behavioral health information and recovery advice to firefighters.

Educational efforts

The relationship between stigma and a fear of seeking help has been discussed throughout this article, and it should be clear how detrimental stigma can be. But what is the basis of stigma? If we get right down to it, stigma is driven by misunderstanding mental illness. Thus, people who know more about mental illness are less likely to stigmatize others than those who are misinformed.7 Fortunately, peer support teams are in a unique position to educate members about behavioral health, thereby reducing stigma.

Many peer support teams request time to speak at recruit schools. Teams can also speak at officer development trainings. These are both good options. Speaking in recruit school can shift the behavioral health paradigm by teaching firefighters at the outset of their careers that mental illness is not a weakness and that there are systems in place to provide assistance. Additionally, speaking to officers has the benefit of reinforcing that it is officers’ responsibility to manage the safety of their crews, including their mental wellness, and that firefighters should not be penalized for needing behavioral health assistance.

Additionally, department-wide education offers opportunities to disseminate mental health information en masse. Talking about mental health sheds light on it. When peer teams educate firefighters about the causes and processes of mental illness and injury, they drive out misinformation, normalize the need for services, and reduce stigma. When we reduce stigma, people get help sooner. When people get help sooner, they are more easily treated. And when firefighters are more easily treated, we reduce suicide.

Resources

Finally, we must examine behavioral health resources. At some point, if a firefighter needs treatment for a behavioral health disorder, he will need to be referred to an outside provider. This is where things can get particularly difficult—and where peer support teams are vital.

Firefighters have a couple of significant fears when they seek outside treatment. The first is a fear of what to expect in any given treatment or therapy. A peer support team that is familiar with area resources and how various treatment programs work can allay those fears by explaining what the firefighter can expect. The second major fear firefighters hold is that they will be referred to a provider who doesn’t understand what it means to be a firefighter. It is up to peer support to ensure that providers understand our schedule and our life. Having providers do ride-alongs or come to trainings or go through a one-day hands-on firefighter basic training program can do wonders for expanding their knowledge of the fire service and for bolstering peer support confidence in referring firefighters to them.

The role of peer support in developing reliable outside resources cannot be overstated. Peer support members will be asked by firefighters which providers they trust, where they would go if they had an issue, and how the treatment process works. If the peer support member isn’t prepared to respond to those questions, the entire team can lose credibility. “Peer team members should build a network of professionals, including psychologists, social workers, marriage and family therapists, psychiatrists, chemical dependency counselors, and clergy.”8 Rest assured that, if the peer support team does a good job developing and vetting resources, word will spread. If, on the other hand, resources are haphazardly developed, word of the failure will spread quickly, too. Vetting trustworthy and reliable mental health providers must be a priority for every peer support team.

The time is now

Providing firefighter behavioral health care offers major challenges in the fire service. As demonstrated, however, peer support teams provide the answers for combatting those challenges. It cannot be overstated that, as more firefighters overcome the stigma of asking for help, we will see the number of our brothers and sisters requesting assistance skyrocket. With that in mind, the time to respond is now. We cannot follow our old methodology of waiting for the flood before building our boat. Instead, fire departments must immediately invest in creating and training peer support teams so those teams can develop the relationships and resources necessary to the behavioral health of our most valuable asset—the firefighter.

References

1. National Association of Mental Illness. Mental Health by the Numbers. 2017. Retrieved from www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-By-The-Numbers.

2. Lee, J., Ahn, Y., Jeong, K., Chae, J. Resilience buffers the impact of traumatic events on the development of PTSD symptoms in firefighters. 2014. Journal of Affective Disorders 162:128-133.

3. Stanley, I. Suicide in the Fire Service: The Truth Behind the Numbers. 2017. PowerPoint presentation [slide 12].

4. Warrior Research Institute. Project PREVENT. 2010.

5. Nugent, P. Psychology Dictionary. 2013. Retrieved from https://psychologydictionary.org/enabling.

6. Place, M. Madigan Army Medical Center. Normalizing mental health starts with you. 2017. Retrieved from www.army.mil/article/186942/normalizing_mental_health_starts_with_you.

7. Corrigan, P. Penn, D. Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. American Psychologist. 1999. 54:765-776.

8. Stelter, L., American Military University. Building a Peer-Support Program for Firefighters. 2017. https://inpublicsafety.com/2017/05/building-a-peer-support-program-for-firefighters.

Brandon Dreiman

Brandon Dreiman is a captain and 22-year veteran of the Indianapolis Fire Department, where he serves as the coordinator of firefighter wellness & support. He also is an International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) Peer Support & Resilience Master Instructor and serves on the IAFF’s Crisis Response Team. Dreiman is a cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) clinician, a Certified Sleep Science Coach, a Certified Addiction Peer Recovery Coach and a yoga teacher. He is the founder of Naptown Yogawalla.