A move toward safety

Our culture of cleaning and care for our bunker gear is finally changing and on the heels of NFPA 1851-2020, which is due to publish this fall, the change is imminent and, in my opinion, will be positive. It wasn’t that long ago when many of us thought the dirtier the gear, the better; that bent, burned up helmet looks cool. Dirty gear was the sign of a “good” firefighter.

It probably wasn’t that long ago when you spread your gear out on the station ramp and washed it with the red line or 1¾, if you ever washed it at all. Think about the last time you washed your firefighting gloves, if ever. Have you ever washed the ear flaps on your helmet? Care and maintenance of all our bunker gear is finally catching up with the science that tells us that dirty gear is unsafe and hazardous to our health.

By necessity, we are changing, and 1851: Standard on Selection, Care, and Maintenance of Protective Ensembles for Structural Fire Fighting and Proximity Fire Fighting, will assist us. Firefighters asked scientists and researchers for the facts and data—and the science is apparent. This edition of 1851 will eliminate the “gray areas” that were supposedly unclear to decision makers trying to decide if they had to wash gear due to some confusion about what “soiled” meant. Indeed, with our brothers and sisters getting sick and dying, cleaning gear after a fire sometimes hinged on an interpretation of soiled, the refusal to apportion budget funds for the solution, or cultural indifference. Although we accepted a certain amount of risk for the operational hazards when we took this job, we put ourselves in harm’s way even more if we refuse to protect ourselves against a scientific and medical certainty after the fire is out.

Changes to NFPA 1851

The new edition of 1851 will update some key definitions and clarify some others. At a glance:

Routine Cleaning has been eliminated. In its place, on scene “wet decon” will be called Preliminary Exposure Reduction (PER). NFPA 1851 will define it as, “Techniques for reducing soiling and contamination levels on the exterior of the ensemble or ensemble element following incident operations.” PER will take the place of Routine Cleaning by mandating it be performed every time PPE is exposed to the product of combustion.

Cleaning will be defined as, “The act of removing soiling and contamination from ensembles and ensemble elements by mechanical, chemical, thermal, or combined processes.”

Advanced Cleaning will be clarified to be, “The act of removing both soiling and contamination generally associated with products of combustion.”

Contamination will be, “The accumulation of products of combustion and other hazardous materials on or in an ensemble element that includes carcinogenic, toxic, corrosive, or allergy-causing chemicals, body fluids, infectious microorganisms, or CBRN terrorism agents.” Realistically, the key now in much of cleaning and care is exposure to the products of combustion.

Inspections will be more frequent from the start. A complete liner inspection of all garment elements shall be conducted as part of the advanced inspection every 12 months and annually thereafter or whenever a problem might exist. The liner system shall be opened to expose all layers for inspection and testing. There will also be a return of advanced cleaning of coat and pant at least once every six months and advanced inspection one of those cleanings. Every time a set of gear receives an Advanced Cleaning it will receive a Routine Inspection after. A set of gear does not require an Advanced Inspection after each Advanced Cleaning.

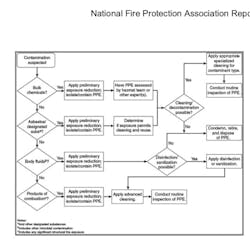

In order to make the decision-making process less “gray,” a flow chart will be provided in the standard (see Fig. 1).Step 1: If you are exposed to the products of combustion

Step 2: Apply Preliminary Exposure Reduction and then isolate/contain PPE

Step 3: Apply Advanced Cleaning

Step 4: Conduct Routine Inspection of PPEA simple way to think of it might be this: If you have to use an SCBA and breathe tank air at a fire, your gear needs to receive an advanced cleaning. This not only includes structure fires but also car, dumpster, and any other exposure to contamination that necessitates bunker gear and breathing tank air. Performing the Preliminary Exposure Reduction does not absolve the department from performing the Advanced Cleaning.

Clarifying standards, increasing accountability

Seems simple enough, but I’ve already heard the reasons why it can’t be done or won’t be done. Instead of reviewing all those reasons, I urge you to stop making excuses and think of ways to make it work. It can be done. Texas, for example, abides by 1851 as statutory law and compliance with the standard is administered by the Texas Commission on Fire Protection. Texas departments large and small have been washing gear after every fire for quite some time. Doing the right thing by our firefighters should have been a no-brainer, but the 1851 Committee was faced with the fact that unless clear mandatory cleaning language was put into the standard, the excuses and outright refusal to perform the cleaning that is needed would continue.

This stipulation to clean after every fire not only applies to coat and pant, but everything else including helmet and ear flaps, hood, gloves and boots. It can be done. Many systems are bagging up at the scene and swapping there, or at a remote location, at a nearby accessible location, or back at the station—all work as long as you bag it at the scene, after you’ve done the PER (wet rinse off). You can also bag your other elements that can be washed at the station or at least give them a soap and brush cleaning on scene, but still wash them at the station.We can clean the gloves, boots and helmet exterior, but the hood and soft goods from the helmet need a separate washing. Many departments are issuing second sets of gear—two hoods (or doing a hood swap), a second pair of gloves, a second set of ear flaps, and yes, a second pair of boots. That makes the logistics that much easier. The Cleaning chapter of 1851 sets out the minimum procedures to be followed.

NFPA 1851 dictates that, “Ensembles and ensemble elements that have been exposed to products of combustion shall be subject to preliminary exposure reduction as specified and isolated, tagged, and bagged at the incident scene.” As you can see, the direction is at the scene. Yes, we may have to have some extra pants or shorts and shoes with us on the rig, but the upside far outweighs the inconvenience. “End users shall carry out preliminary exposure reduction immediately after exiting the emergency scene at any incident where their protective ensemble or ensemble elements could have become soiled or contaminated.” It will also state that, “Following dry or wet mitigation, ensemble or ensemble elements shall be isolated and bagged. Ensemble or ensemble elements, even when bagged, shall not be transported in the passenger areas of apparatus or personal vehicles.” Yes, there may be situations where these procedures will not be practical; freezing weather, driving rainstorms, etc, and we’ll have to deal with them and maybe come up with some outside-the-box thinking.

While the coat and pants will be cleaned in a station extractor or sent to an independent service provider (ISP), we also need to pay equal attention to the other elements; helmet (including ear flaps), hood, gloves and boots. The standard will still reference element manufacturer’s cleaning recommendations. All of these items must be cleaned after each fire, just like the coat and pant. The importance of cleaning these items has increased with some studies done in the past few years. The permeation of contaminants through hoods shown in the FAST test, along with the 2010 UL study Firefighter Exposure to Smoke Particulates identifying the significant contamination levels in firefighting gloves, are the scientific proof. If you need a visual for convincing, wash the gloves into a bucket or a sink with a stopper in the drain. It will be an eye opener, especially if it’s the first time you’re washing them. Soak your hood or ear flaps in a bucket before you wash them—it’s a convincing visual.

The PER process is not that difficult. I say this because I’ve done it. After being the first truck into a working fire, my crew did the on-scene rinse after coming out of the fire after a second bottle, we stayed on air until it was done. We rinsed from the top down at one half pump pressure, or, garden hose pressure. We went to rehab and when overhaul needed to be done we volunteered to go back in and finish overhaul—on air and in full PPE. We did the PER again (on air) upon completing overhaul. After rehabbing again we isolated all of our PPE in a couple of compartments and returned to the station. It can be done. A PER with soap and brush can also be done. While it may take a little while longer, it gives you the increased ability to remove the exterior contaminants from boots, helmet, gloves and SCBA.

We now use a system that has a firefighter on duty 24 hours in a “remodeled” ambulance that comes to a station closest to the fire scene and picks up dirty bagged gear to receive advanced cleaning in an extractor and swaps out a clean second set that is each firefighter’s back up set—we have two sets per firefighter. We perform advanced cleaning of the other items including helmet, gloves and hood back at the station according to each element manufacturer’s directions. Firefighters must take the responsibility of performing cleaning of those items. It’ll take about as much effort as washing the rig and using a brush on the tires and rims. Don’t forget about the ear flaps.

Research continues

In reality, no one associated with our business should need to be convinced. There’s enough evidence already out there and available. The good work that has been done and continuing on by the Fire Fighter Cancer Support Network, the Illinois Fire Service Institute, UL, Intertek, the University of Arizona, NIOSH/CDC/NPPTL, University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, Boston Fire Department, Washington State Fire Fighter Council, Fire Protection Research Foundation, IAFF, and others is readily available.Recently, I learned that a brother I came in with has Stage 4 lung cancer. It hit particularly hard because his only risk factor was that he has been a line firefighter since we graduated drill school. We’ve buried four of my fire department brothers since 2014 and our number of active cases (that we know of) is 36—about 2 percent of our department. The men who died were friends from our fire department family. I worked with all of them at one time or another and one worked for me. They joined in different years and died with different amounts of time on the job, all far too young.

The numbers nationally are staggering and this mandatory cleaning after each fire is a giant step in the right direction. Every day we clean the rigs, clean the station and put on a clean uniform, yet there has been reluctance to clean our most critical personal protection. Ultimately, from the most senior chief to the newest rookie, we must make sure that these changes are implemented and followed. It can be done and will be done because the people that it affects the most—the firefighter—will make it work.

About the Author