Building codes and local, state and federal laws can present a labyrinthine path to securing the approvals, permits and compliance with legislation required to commence construction of a new or renovated fire station or emergency facility project and to mitigate lingering liability. While your department or district’s architect (and code consultants if on the team) should be the lead for navigating jurisdictional requirements, this article will provide fire service representatives insight into compliance complexities, interpretations and risks.

Code basics

Authorities having jurisdiction (AHJs) adopt, amend and enforce model codes at the local level. Prior to the year 2000, the model code landscape in the United States consisted of three main regional codes: the National Building Code on the East Coast and in the Midwest, the Uniform Building Code in the West, and the Standard Building Code in the Southeast (now collectively known as the Legacy Codes).

The International Code Council (ICC) launched the International Codes Series (I-codes) at the end of the 1990s as a singular replacement for the regional model codes. In addition to the International Building Code (IBC), the series includes volumes for Fire, Mechanical, Existing Buildings, and others. The ICC publishes revised I-codes every three years, and AHJs review, amend and adopt the new codes on their own schedule. Your AHJ’s website is the place to start to find codes and amendments in effect, but bear in mind that the codes are scoping instruments and make reference to an alphabet soup of published standards, methods and tests for achieving compliance (e.g., ASTM, UL, NFPA, ISO).

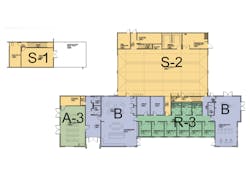

A fundamental difference between the legacy codes and the IBC is the classification of building use. The legacy codes typically classified buildings based on a single use while the IBC classifies buildings based on occupancy types. As a result, a single building now often contains multiple occupancy classifications. So, whereas a fire station would be considered a Type B (Business) under the Uniform Building Code, it may now look like a mix of B (Business), R (Residential) and S (Storage, which includes garages). The IBC then provides provisions for separating individual occupancies (fire-resistive construction) or designing with restrictions for non-separated occupancies. The IBC also began to increase incentives for using NFPA fire sprinkler systems, for example, allowing for larger building areas and reduced fire-resistance ratings where required between spaces.

Additionally, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law in 1990. The law scopes a series of standards for accessibility for the disabled (e.g., 2010 ADA Standards). Requirements for fire stations as public buildings are scoped under Title 2 of the Act, and public facilities are subject to higher accessibility standards than commercial and residential developments.

The ADA is enforced by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), but the DOJ is not involved in local building permitting. Instead, the local AHJ assesses accessibility compliance based on IBC scoping and a separate accessibility standards document titled the ANSI/ICC A117.1. The DOJ reviews accessibility requirements based on complaints or local government audits—after a project has been built.

While the ICC and ADA have worked to align their standards, the answer to the question of who’s in charge of accessibility enforcement is both the local and federal government. So, convincing a local building official of an interpretation of an accessibility requirement is no guarantee the DOJ wouldn’t find an issue during an audit years from project completion.

Energy code adoption and requirements vary greatly in scope between states and AHJs. Stricter energy codes will drive higher construction costs but can offer dividends in savings over the operational life of a facility. In addition to the environmental benefits, more efficient energy use means a reduced long-term cost of ownership, which is why some cities are implementing Net Zero Energy building policies, where a facility must produce as much energy as it uses on a net annual basis. Recent examples include Salt Lake City Fire Stations 3 and 14.

Code considerations for fire stations

Inclusion of an NFPA fire sprinkler system will allow for greater allowable area, height and a reduction in separation and other code requirements. In the state of Washington, sprinkler systems are required for fire stations by law. If your AHJ offers the choice, then you and your team will need to evaluate code breaks, costs, safety considerations, and the example you want to set in your community.

With a sprinkler system, most fire stations can take advantage of the non-separated mixed occupancy IBC approach in lieu of fire-resistive separations between varying occupancies. This will save cost and generally allow for a more open and efficient station (e.g., fewer doors to get from a bed to an apparatus). However, your team will need to understand separation requirements outside of the building code. For instance, Washington State also requires a 1-hour separation between apparatus bays and sleeping rooms. This makes some sense, in a home, and the International Residential Building Code requires a 30-minute separation between a garage and living areas.

The IBC provides a tiered approach for the required structural performance of a building, and as an “essential facility,” fire stations are subject to the strictest structural requirements. While an office building is required to be built to protect life in the event of a disaster, which means the occupants survive but the building may be condemned, a fire station must be designed to protect life and be immediately occupiable post-disaster. This means a fire station will be better able to resist the shaking of an earthquake or the high winds of a hurricane. The code also maps out exposure risks, so, for example, if you’re in seismic or hurricane country, more dollars will go into the structure of your station.

With a few exceptions for building support spaces, fire station facilities, as Title 2 Public Buildings, are required to be fully accessible for disabled staff and the public. Accessibility requirements extend to the building site, including accessible parking stalls for cars and vans as well as an accessible pedestrian path from the public right-of-way to the building entrance. ADA standards touch most every aspect of design, from the maximum opening force of the front door to the exact width of a shower stall. Building elements such as hallways and restrooms require additional square feet for maneuvering and fixture clearance requirements.

While optional for single-story stations (but a poor appropriation of public dollars!), elevators are required as part of the accessible path of travel for multi-level stations. Cogent arguments have been made for why some areas within a fire station should not be considered public or accessible, like a sleeping room. And similarly, convincing cases have been made relative to the mandatory fitness requirements for staff (able-bodied). Nonetheless, the ADA law is clear: Spaces are not exempt based on a policy that excludes persons with disabilities from certain work, and a fire facility is considered a public building in its entirety.

So, what does this look like practically: An injured firefighter on light duty may make use of an office space; a student in a wheelchair can be included in a station tour and see where a firefighter sleeps; or an elected official with a walker may tour the facility.

The DOJ does recognize certain spaces used by first responders are “non-transitory residential.” They have published guidance that supports an “adaptable” approach to kitchens and bathrooms in the crew area. This allows for kitchen sinks to be placed at standard height (36 inches) as long as provisions are made for lowering the sink to ADA height (34 inches) should it ever be required. Shower stalls can be installed without seats and grab bars, as long as blocking is provided in the walls should these elements need to be installed. We’ve found local building officials generally inclined to accept the adaptable approach when provided with the DOJ guidance document. If your architect is unaware of the approach, you can now clue them in!

The application of building codes and accessibility requirements for the addition and/or remodel of a building adds additional complexities. Most AHJs have adopted the International Existing Building Code for this project type, and the ADA concept of “disproportionality” provides a 20 percent ceiling for the portion of project construction cost applied to accessibility upgrades.

Interpretations

A measure of the room for interpretation of the IBC is the two-volume set of commentary that the ICC publishes to help illuminate the meaning of code requirements. This is the space where your architect will need to provide guidance while applying the codes to your building design, for instance, when classifying an occupancy type for a kitchen (is it residential or business?) or assigning the maximum occupancy of a training room (will it ever be standing room only?). It is important to be aware that plans-examiners (who review plans prior to permitting) and building inspectors (who review for compliance during construction) are typically separate jobs by separate individuals with varying degrees of experience. A building inspector may cite non-compliance with the code on an item where no permit review comments were provided. When this happens during construction, it can be a challenge to appeal and, if unsuccessful, expensive to correct.

How to mitigate this risk?

- Document all code interpretations during permit review: Your architect should provide a code analysis as part of the permit submittal. Dialogues with the building officials regarding compliance need to be documented.

- Hire experienced design professionals: Your team must understand the code requirements salient to your specific project type.

In preparation for this article, we sat down with Codes Unlimited (CU), experts in the code world, and discussed the evolution of building codes and when to add a code consultant to your team. CU noted that as codes have evolved, both the complexity of requirements and areas for interpretation have increased. Sometimes it takes several code cycles for a requirement to be clarified. For instance, is a single-occupant firefighter sleeping room part of an R-2 or an R-3 dormitory occupancy? (We do believe the 2018 IBC and Commentary will provide the clear answer to this question.) CU points out that a code consultant can add an expert to your team who can negotiate compliance paths and document understandings reached with AHJs on behalf of the owner. Code consultants are seasoned professionals who bring clarity and decisiveness to answering code questions, and guide owner thinking about which safety investments provide the best value and reduce the most risk.

In conclusion

We hope this article has shed some light on the evolving complexity of building codes, their application to fire stations and emergency facilities, and the gray area for interpretation. Districts and departments rely on the professional services team to lead the way through the code maze, secure approvals and permits, and obviate construction and occupancy compliance risks. So, their most important decision is selecting the right team for the project.

A final thought: Codes provide the minimum requirements for life safety. Samir Mokashi, founder of CU, offered, “Safety is an important design value; our experience is that the building occupants assign a higher value to it than what the designers or program managers assume.”

You may elect to exceed a safety requirement, or you may recognize lobbying for a liberal interpretation of a code requirement may save upfront dollars but reduce safety and increase exposure to risk over the life of your facility. There are many important considerations for owners whose business is safety!

Sidebar: Additional Information

International Code Council: iccsafe.org

Department of Justice Guidance (page 16): ada.gov/regs2010/2010ADAStandards/Guidance_2010ADAStandards.pdf

Federal Access Board Videos: https://tinyurl.com/federal-access-board

Brian Harris

Brian Harris AIA, LEED AP, NCARB, is principal/president of TCA Architecture + Planning and is a co-founder of the Station Design Conference 1-on-One sessions. He has been instrumental in the design of more than 325 fire facilities in 18 states, won more than 65 design awards and authored many forward-thinking fire-facility planning and design articles. Harris speaks frequently at national fire facility conferences and is the director of design education for the Washington Fire Chiefs fire facility section. He designed the first LEED-certified fire station and the first LEED training facility in the United States and worked on the first two Net Zero-Energy fire stations in the country.