Willis and Willingham: A Call to Action for Fire Investigators

In 2011, the Texas Forensic Science Commission (TFSC) released a report that focused on the arson cases of Ernest Ray Willis and Cameron Todd Willingham. The value of this document, which urges fire investigators to fine tune their work by utilizing the scientific method, can’t be denied.

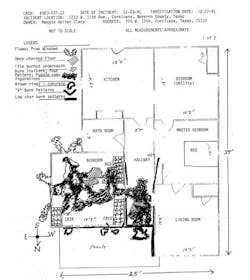

The report reviewed the cases of Willis and Willingham, both of whom were sentenced to death based on virtually identical assumptions, findings, and conclusions by the state of Texas and local arson investigators in 1986 and 1992 respectively. Both men were accused and convicted of setting fire to houses, resulting in fatalities. That is where their stories cease to be identical—Willingham was put to death by lethal injection in 2004, the same year Willis was set free, following the reopening of the case at the urging of the Texas Innocence Project.

TFSC report

The TFSC report includes a case summary divided into three parts: Executive Summary, Introduction, and Methodology. In the Executive Summary, the report states that neither fire was, in fact, incendiary. It also says that evidence examined by the original investigators is routinely created by accidental fires when they lead to flashover. The expert witnesses for the report stated that interpretations of these indicators, which led investigators to the arson conclusion, were proven “scientifically invalid.”

This portion of the report then states that investigators who still interpret low-burning, irregular fire patterns and collapsed furniture springs as being signs of incendiary fires will “continue to perpetuate miscarriages of justice.” The report stresses the need for investigators to continually train and undergo professional development. It also notes the need for other justice system participants to continue their education and be skeptical of opinions that do not include scientific support.

The Introduction portion of the report states that fire is governed by the laws of physics and, to reach accurate or valid determinations, investigations of fires must apply the scientific method as do all other physical science investigations.

Finally, the Methodology part says that, to prosecute arson, a bifurcation is associated with the burden of proof. First, the state must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a fire was, in fact, an intentional act. Second, if it was intentional, the state must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that this fire was set by a specific individual.

The last portion of the Methodology section says that the fire investigation expert should communicate findings to the jury and, during the second determination, ratifies the investigator’s determination. The final 800-plus pages of the report focus on the process of researching these cases and 17 recommendations from the commission.

Before investigative standards

I’ve been blessed to be part of the discipline of fire investigation for over 22 years, and I must admit that my predecessors were not necessarily portrayed in a flattering light in the report. These cases, however, occurred before any real investigative standards existed—so, why should we care? Because we should all be committed to continuing to learn and become more exacting in our investigation lest the cliché about history repeating itself become a reality.

Many of the problems and shortcomings discussed could help us become better investigators if we set our own egos aside, are willing to accept new science validation, and adopt scientific methodology as our standard and guide. The proven five-step process promotes thorough and specific examination of the evidence and lends itself to more precise results.

We should also seek professional-level training, as well as basic remedial training. Professional development models such as National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1033: Standards for Professional Qualifications for Fire Investigators and NFPA 921: Guide for Fire and Explosion Investigations are available and valuable. The 1033 Standards and the 921 Guide could help prevent any professional investigator from repeating what occurred with Willis and Willingham. Regardless of any individual opinion about the April 11 TFSC report, no investigator wants to wrongly put someone in prison.

Ultimately, we have these established standards and guides that help us justify continued education to our agencies, and we have the responsibility to seek justice. This authority, in the end, can cause someone to lose his freedom, which no agency wants to do haphazardly. Regardless of agency size and whether fire investigation is routine or a rare occurrence, those investigating should be in training. Failure to utilize all available training and technology could result in being vulnerable in court.

In future articles, we will further examine both the Willis and Willingham fires.

Collin County Fire & Arson Investigators Association, which I have the honor of heading up, is sponsoring the fourth annual fire death investigation course later this year. Held in conjunction with Eastern Kentucky University, Sam Houston State University and the Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office, it is slated for Sept. 26–30, 2016, at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, TX. To participate, download the packet at http://tinyurl.com/oeb2ys9 or contact me at [email protected].

STEVE SEDDIG has been a member of Wylie, TX, Fire Rescue since 1994 where he currently serves as fire marshal and division chief. He is the elected president of the Collin County Fire & Arson Investigators Association and was instrumental in bringing to Texas one of only two fire death investigation courses in the country that uses human case studies. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Emergency Administration from the University of North Texas in Denton, an Associate of Applied Science—Fire Science from Collin College in Plano, TX, and Associate of Applied Science—Law Enforcement Technology from Rio Salado College in Tempe, AZ.