Fire Officers: What Would You Do When No One is Watching?

As a fire officer, you are a direct front line representative for your respective department. You greet the public at many different instances, from the wide-eyed child that wants to grow up and be a firefighter, to the couple who stare at the charred remains of their lives work, looking for answers to where to begin from here. There is a significant balance needed to be able to handle these incidents and keep the balance between the brass and the crew members, along with keeping a keen focus on our customer service delivery. We are the problem solvers, the reassuring voice, the unyielding sign of confidence and determination while ordering troops into a raging inferno, while the spectators stand agape with wonder.

Recently, a fellow fire service professional was telling me about an issue that arose at a meeting of the rank and file in his department. It seems as though this department has firefighters who act in an officer capacity when the company officer is not on shift, for whatever reason. A member raised a point; he stated that everyone in the department should be able to serve as an acting officer. His reasoning was that “…everyone was the same…” and he continued on to discuss the financial perks that come with riding the front seat, and he deserved some consideration in that matter, regardless of this member’s training and capabilities. Actually, many officers who I relay this story to become highly insulted, as these comments can only serve to lessen the efforts of those assigned these responsibilities took to ensure the safety and efficiency of their respective companies.

Let me make my position crystal clear…There is a significant difference when making the transition from firefighter to company officer. A look at the headlines recently reminds us just how dangerous, and fatal, our jobs can be at any call, at any given moment. We in the service must insist on competent, effective leaders in our departments to serve as officers; it isn’t enough to just be lucky, these days you have to excel at commanding operations on the fireground.

Admittedly, I am not surprised by the comments of this person. There are constant examples of “leadership turned entitlement” in our profession, and it is making our fireground operations much more hazardous. Want proof? Just read through some of the recent line-of-duty death (LODD) reports at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) website, and you will see some of these consistent themes in each one:

- Lack of a sound understanding of fire behavior, and extreme fireground dynamics;

- Lack of a proper size-up (risk vs. gain) early into the operation;

- Lack of understanding of extreme fire effects on lightweight construction;

- Lack of existing standard operating procedures (SOPs);

- Lack of use of an Incident Command System;

- Lack of sufficient training;

And the list goes on and on. Who has the responsibility to control each of these issues? The Officer. Do these responsibilities sound like something to bestow upon someone who feels like its “their turn” to be the boss for the day?

Officer/Leadership Characteristics

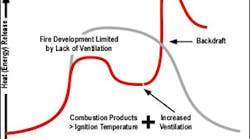

First and foremost, the company officer must have a sound background in every aspect of response that is provided by the department. While many departments provide a wide variety of services, such as EMS, Hazmat and Technical Rescue capabilities, there are two areas of knowledge that stand out above most other topics: Fire Behavior and Building Construction (photo 1). The foundation of our job is suppression, so it is imperative that fire behavior is second nature to the officer. As fire loads and heat release rates have increased exponentially over the years, our basic training in boot school regarding fire behavior is only scraping the surface. Many websites provide great training and proven factual information in regards to fire behavior. Continuing education in this area includes study in Fuel Loading, Air Tracking and Compartment Characteristics. Each area is equally important, and there are great training opportunities and study materials available for the aspiring officer.

I started my career in the fire service over 25 years ago, dealing with stubborn fires in durable structures; today’s responders are facing potentially explosive fire behavior while contained in what are referred to as “disposable buildings.” The introduction of lightweight materials, engineered structural components, and increased flammable sheathing has significantly reduced the time we have to mount an offensive attack within newer compartment fires. Understanding construction methods and material shortfalls are vital for the officer. The initial size-up must take these factors into consideration when choosing a mode of attack upon arrival, based upon the appropriate level of risk the situation is dictating.

The officer must also serve as a leader to the members of the company as well. While there are essential characteristics for emergency scene skills, officers should possess other leadership traits as well:

Strong Tactical Focus: Fire officers who serve as Incident Commanders need to have a thorough blend of tactical competency and “street smarts”; assigning companies to specific tasks based upon the situation at hand comes from a strong knowledge base and detailed comprehension of the response area (photo 2).

Discipline: Officers must set the example; doing the right thing the first time, every time, sets a level of acceptable behavior within the company, while allowing enough ability to be flexible when need be.

Inspiration: An officer should inspire their company members to strive to do their best. Being able to motivate the company members will enhance their skills during an emergency, increasing the level of service they provide.

Know Your Troops: Each member brings a variety of skills to the team; a good officer should identify each member’s strong points and allow them to apply them to the incident.

Be Involved: The officer should be visual, and have their hands in every aspect of the company’s daily assignments. Getting involved in equipment checks, maintenance and repairs, inspections and station operations helps to solidify the Esprit de corps, or the morale of the company.

Accept feedback: A wise Chief Officer once told me that we are given two ears and one mouth for a reason. Being a good listener is vital for an officer; decisions during emergencies require as much information as possible to arrive at the correct decision. Listening skills requires full attention to the details before beginning to develop a response to the information.

Be Decisive: At times fire officers can suffer from “Paralysis by Analysis,” taking so much time to make any decision, while time on the emergency scene is critical. It is wise to practice “Tactical Patience”; taking a breath, so to speak, to get all the size-up information right to make the right call the first time (photo 3). But, make the call so the companies can get to work. Being able to make sound decisions and show assertion while doing so will increase confidence in the members of the company.

Walk the Walk: Credibility comes from the decisions that the officer makes. Wearing their personal protective equipment (PPE), stepping off the apparatus with a tool in their hand, operating with everyone’s safety in mind, and “getting dirty” with hands-on training are just some of the things the officer can do to show the troops that they are in good hands.

The Consummate Example

Rank as an officer is a title that can be, at times, given far too often before it is earned. Many times we get promoted or appointed, and we start a new “pseudo-career” as an officer within the one we began when we entered the fire service. It is not enough to just have the title; while it may have been given, it still must be honed and polished throughout one’s career. Throughout my career, I have earned many titles, and I am proud to have each of them. I have been called lieutenant, loo, Instructor Daley, Master Instructor Daley, Mister Daley, Sir and Daddy (that one’s my favorite), but each of these titles are switched like disposable name tags at a speed-dating event, depending on which hat I am wearing that day. There are very few people who come into our lives that hold a title permanently, no matter what the audience; they are called mentors. I have a few; it is important to be able to draw experience by example from multiple resources. There exists many great examples of this in the service; these people have earned the respect and admiration of their peers, and the rank is bestowed upon them, not out of procedure, but out of respect.

I would like to tell you about The Chief.

I have worked at my local fire academy for close to 22 years, and from the moment one walks through the door on their first night, it is a humbling experience. Humbling, because once you leave your personal comfort zone, you find that there isn’t a shortage of well-trained, competent firefighters in your demographics. You honestly believe that you are on your game as a firefighter, and then you find out how much you still have to learn. Some instructors stay the duration, some stay until other responsibilities get in the way, and some stay far too long. Unfortunately, some do not stay long enough.

My tenure in the fire academy, hopefully along with my capabilities, allows me the privilege to serve as a Lead Instructor for the recruit classes that enter our hallways each semester. However, every semester, I make it clear that I will stand aside and follow the leadership of The Chief during Boot School. The Chief has been with us for over 20 years, and a lot more frequently since he retired from his position as a Deputy Chief of a very busy fire department in Central New Jersey. His disposition and demeanor on an emergency was second to none; in fact, in all the years I have worked with him, both in a training capacity and during an emergency, I cannot think of a single time where he was without grasp of his surroundings. Those who served under him followed his lead without question, for his way worked, every time. His delivery as an instructor, coupled with his calm demeanor on the fireground, made him a natural leader, even for his peer instructors. There were no shortcuts, no doubts, no second-guesses; any doubts about his orders eroded once he demonstrated it. He would never ask anyone to do anything that he wouldn’t do. If you were at the academy looking for him, you would find him early in the morning, about an hour before class started, sitting in the cafeteria, “holding court” with a bunch of recruits feverishly taking notes as he spoke of skills and techniques of our job with a hot cup of coffee in his hand. Moreover, he would listen to their questions, concerns and fears about their new journey, only to remind them of the rewards that await them from doing this job. So for the last few years, the decision to follow The Chief’s lead was an easy one for all of us to make.

This past semester, I served as the Lead Instructor for the Recruit Class. The Chief was unavailable to take the reins; a significant issue required his full and immediate attention. I took the reins begrudgingly, as all of us would prefer to see The Chief bark out orders and set companies into motion on the fireground, no matter what the task. We all followed his lead, even when he wasn’t there to lead it himself.

About six weeks into the recruit class, the training grounds were full of activity; smoke filled cellars with PASS devices sounding for “simulated” firefighter/mannequins down, with students following hoselines to get themselves to safety, while emergency ladder slides from second floor areas were being conducted with instructors keeping a watchful eye on the progress. Instructors were manning belay lines for sliding students, hose lines were covering recruits finding their egress, and radio reports for “victim removals” were being transmitted to the Lead Instructor as the “fireground” was alive with activity. Around mid-point through the session, a familiar car pulled up, and parked on the A/D corner of the training grounds. Two people sat in the front of the car and watched our progress. I stared at the vehicle for a few minutes; then the Chief rolled down the passenger window.

Everything stopped…

Students watched as every instructor made their way to the passenger door, wanting to greet the chief, just to say hi and greet his wife. In a true example of The Brotherhood, each and every one of us reminded The Chief and his wife that the “family” is here, and we stand ready to do what is needed. We all would stand ready, for that is the true meaning of “The Brotherhood” that we enter when we “boot up” for the first time. This “Brotherhood” needs to be re-visited and re-energized, for next to our own families, we owe our second “family” members the same respect that we would want in our own time of need.

I had to get back to work, but I wished I could stay by the window for a bit longer. I shook The Chief’s hand, and told him I would call him in a few days. He and his wife watched for a little while, and then quietly drove away. I was standing by our aerial during the remaining evolutions, keeping watch as The Chief would time after time, making sure there were no shortcuts, no doubts, no second-guesses; keeping the standard he set for us. A short time later, one of the students approached me, shook his head, and said one of the most profound statements I have ever heard anyone in the fire service say, yet alone a recruit:

“You know, I watched every one of you instructors stop what you were doing, walk over to that car, and shake that man’s hand. I don’t know who that was, but I know one thing; I want to be him.”

“Yeah…” I added, “so do I.”

Godspeed, Chief. Well done. We are forever grateful to you for showing us the way…

We will take it from here.

Until next time, stay focused and stay safe.

See Mike Live! Lt. Michael Daley will be presenting “Basement Fires” and “Strategies and Tactics for Fires in Attics and Cocklofts” at Firehouse Expo in Baltimore, July 23 - 27.

MICHAEL P. DALEY is a lieutenant and training officer with the Monroe Township, NJ, Fire District No. 3, and is an instructor with the Middlesex County Fire Academy, where he is responsible for rescue training curriculum development. Mike has an extensive background in fire service operations and holds degrees in business management and public safety administration. Mike serves as a rescue officer with the New Jersey Urban Search and Rescue Task Force 1 and is a managing member for Fire Service Performance Concepts, a consultant group that provides assistance and support to fire departments with their training programs and course development. You can reach Michael by e-mail at:[email protected].

Michael Daley

MICHAEL DALEY, who is a Firehouse contributing editor, is a 37-year veteran who serves as a captain and department training officer in Monroe Township, NJ. He is a staff instructor at multiple New Jersey fire academies and is an adjunct professor in the Fire Science Program at Middlesex County College. Daley is a nationally known instructor who has presented at multiple conferences, including Firehouse Expo and Firehouse World. His education includes accreditations as a Chief Training Officer and a Fire Investigator, and he completed the Craftsman Level of education with Project Kill the Flashover. Daley is a member of the Institution of Fire Engineers and a FEMA Instructor and Rescue Officer with NJ Urban Search and Rescue Task Force 1. He operates Fire Service Performance Concepts, which is a training and research firm that delivers and develops training courses in many fire service competencies.