All belay lines must be connected dorsally to a Class 3 harness. All knots require safeties. Two-tensioned rope systems solve all problems. All technical rescues and trainings that were conducted over the past 50 years used NFPA-certified gear.

Are you curious as to why these principles exist? It’s good if you are, because rescuers who are dedicated to their craft never stop learning—or taking classes for that matter.

In my journey, one of my favorite authors, instructors and mentors is Bruce Smith. Smith is the co-author of “On Rope: North American Vertical Rope Techniques” and the former owner of On Rope 1. In his course materials and on his website, he always maintained a fun and informative section titled “Rope Myths.” He would outline dogmas, fallacies and general rope tomfoolery in both brief and cheeky prose. This column is inspired by Smith.

Another great author and instructor, Pat Rhodes, writes similarly in his texts in sections titled “What’s In” and “What’s Out.”

In researching and preparing for this column, I found myself reaching out to an inner circle and reading about myths. Coincidentally, most of the myths that Smith and others tried to dispel decades ago still flummox instructors and practitioners of the craft today. On the other hand, in a world that’s eager to embrace two-tensioned rope systems (TTRS), industrial rope access, work-at-height regulation and lightweight systems, some modern myths deserve some discussion and clarification.

Let me be clear: In this world, I rarely deal in absolutes. Standards and manufacturer recommendations use words clearly, including “shall”and “should.”Take the following with a grain of salt, because I am very reluctant to use the terms “always” and “never.” However, my response to the barrage of questions that instructors are asked often begins with, “It depends.”Knots

The preferred knots in rescue have wide-ranging properties: recognizable, secure, easy enough to remember, multifunction. One of the often overlooked but desirable traits is ease of untying. This is the reason that sailors use the bowline to secure ships at port. The knot can be untied.

In the ’80s, when our community didn’t have a thorough understanding of nylon kernmantle rope, there was a great fear of unexpected and catastrophic failure at the knot. This was part of the conversation regarding safety factors, 15:1, 10:1 and the impetus of the Kootenay Highline. Because the simple bowline typically was weaker in strength to the figure of eight on the bite and easily untied, it would become shunned for much of the ’90s and 2000s.

The bowline family has more than 200 variations. The knot is extremely useful, and a rescue school in the Southwest has helped to perpetuate its use in rescue circles.

The bowline family is the most versatile of all of the rescue knots. To remain secure, when bowlines are cyclically loaded and unloaded, they require the tail to be secured or safetied. Most firefighters are taught to tie an overhand on the bowline loop. A popular alternative is to trace the tail around the loop and retrace out parallel to the standing part of the rope. This technique is called the Climber’s or Yosemite finish.

The point is that the bowline is a knot that can be versatile and easily untied and requires a safety for live loads.

Somewhere along the line, the application of an overhand safety got carried away. I’m uncertain as to whether to attribute this to groupthink, book publishers or just a bad case of the good-idea fairy.

No empirical evidence suggests that the figure-of-eight family benefits from the addition of an overhand safety when pulled to failure. Many schools choose to teach that a retraced figure eight follow through or figure eight bend should be safetied because the rescuer might have made an error retracing.

There are knots that benefit from safeties and ones that don’t. If it unties easily, a safety is beneficial. For example, square knots, clove hitches, bowlines and some retraced knots benefit from an appropriate safety. However, as time passed, we fooled ourselves into believing that everything needs a safety. A figure eight on the bite, midline knots, double fisherman knots and many others don’t require this step. Often, time is wasted untying and retying a knot to acquire sufficient tail for a safety. It’s more important that a knot be dressed, set, loaded and of a small bite only for the necessary connections.Harness use

Rescuers employ rules of absolute in several areas in harness use: rescue requires a Class 3 harness; belay attachments always must be to the dorsal ring; ropes must be attached to the harness in separate places. Like a good firehouse wisecrack, most of these statements are rooted in truth, but there certainly are times where these aren’t accurate statements.

The first statement—rescue requires a Class 3 harness—is self-evident, given that NFPA has had three different rescuer harness classifications since the first edition of NFPA 1983: Standard on Life Safety Rope and Equipment for Emergency Services in 1985. Full body harnesses aren’t required for all rescue environments. (In fact, “shall” and “full-body harness” aren’t used in many places except in the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s 1910.146(k)(3)(i) standard on confined-space rescue.) It really comes down to a desire for cost savings. Most organizations default to a one-harness solution. This usually happens to be an NFPA Class 3 full-body harness that has a dorsal ring. Rescuers who perform surface rescue in wildland-urban, backcountry and similar areas often use Class 2 sit harnesses.

There are great lightweight full-body harnesses that aren’t Class 3 and don’t have a dorsal ring. The decision comes down to the user and the environment.

Fall arrest

Generally, our European counterparts are ahead of us in rope access and fall arrest. They use the sternal attachment for belays and fall arrest. The “must” and “shall” in the United States for the use of dorsal attachments stem from facilitating nonentry retrieval in confined spaces and in instances where more than two feet of freefall exist. This is a requirement of the American National Standards Institute for fall-arrest lanyards and harnesses.

Forward-thinking colleagues all over are using the sternal for the belay or fall arrest. This allows for a favorable position of suspension, better ability to protect the head and face during a fall event, and increased ability to self-rescue. If you don’t believe me, try a self-rescue maneuver when suspended from your dorsal connection.

TTRS once again are in vogue because of some really amazing advances in technology. With this enhancement, rescue teams that suffer from “redundititus” must be able to see where redundancy begins and ends.

We don’t wear two harnesses, we don’t don two SCBAs and I never saw a fire truck with a brake pedal for the officer.

If your team employs a TTRS and you attach to different points on the harness, interesting things happen. You might be seesawed back and forth between ropes and you won’t be sitting in your harness as intended.

I look at an appropriate attachment as a “closed loop” from an ISO 9001 manufacturer. The strength usually is 3,600–5,000 lbs. There is no human influence. Some fall-arrest and rope-access schools refer to these as “redundant by design” or “engineered to the point that redundancy isn’t necessary.” The same goes for rigging plates and bull rings.

When using TTRS, connect both lines to the same point on the harness. Allow the quality of manufacture and exceptional engineering to provide the redundancy.

TTRS

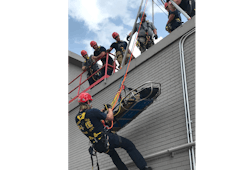

The rescue community has reached a transcendence in technique and technology that has thrust TTRS into the mainstream. That said, a TTRS isn’t the answer to all problems. Instead, they are tools in the rescuer’s toolbox. There are times when a dedicated main with a dedicated belay (DMDB) still is the best option.

The benefits of TTRS include limiting fall distances and forces, better rope protection, the use of like devices and easily accomplished knot-passing.

Rescuers should practice mitigating some of the TTRS challenges. These include how teams manage the devices and their reaction time in failure. I recommend utilizing a rope-tailing technique that backs up the rescuer(s) on the handle. When using a TTRS, anchors and their components must be suitably strong if co-locating both devices. If a high directional is present, it must be secure and competent enough to hold both halves of the system.

Edge approaches and transitions can be tricky, too. It almost is impossible to maintain tension during the approach and through the edge transition. Many teams run a DMDB until the edge transition is complete.

Good practitioners should maintain a solid working knowledge of both TTRS and DMDB techniques and know when to leverage the capabilities and limitations of either system to meet a given challenge.

NFPA compliance and certification

NFPA compliance and certification usually comes up in a class or clinic when a participant makes a statement to the effect of, “We can’t use it if it isn’t NFPA 1983 G-certified.”

What if we had been using proven techniques since the inception of NFPA 1983 that were never certified? Well, we have. Let’s consider a 3:1 Z rig that’s attached to a tree with a wrap-three-pull-two anchor. The progress capture is an 8 mm triple-wrapped Prusik, and the haul cam is a Gibbs ascender. This mainline system has saved people for half a century without issue. The accessory cord, Prusik hitch, tubular webbing and ascender aren’t NFPA-certified. To someone’s great disappointment, even with a new half-inch G-rated rope, the safety factor for 600 lbs. is around 7:1—but still, no problem.

NFPA is a great tool for manufacturers, and rescuers can take comfort in the knowledge that NFPA certification has required third-party testing since 1990. However, rather than simple NFPA compliance, rescuers should focus on sourcing their equipment from proven quality manufacturers. The rigorous ISO 9001 certification that many of these manufactures maintain ensures high quality and consistency in sourced materials.

Some great tools that don’t hold NFPA 1983 certification are used widely: tubular webbing, Prusik hitches, accessory cords, many hard cam rescue ascenders, chest ascenders, handled ascenders, mobile fall arresters, fall arrest lanyards (Y-Lanyards), wire rope fall arresters.

So, try not to lose sleep tonight. Remember to focus on quality gear from quality manufacturers that you use within the manufacturer’s guidelines or proven best practices.

It's on you, too

Much like a beloved kids show stated, you don’t have to take my word for it. Test your own systems. Read manufacturers’ literature and test results. Research for yourself in places such as ITRSonline.org. After all, some myths are older than I am, are based in truth and are far from absolute. I am just another colleague and friend standing on the shoulders of the giants, such as Bruce Smith, who came before me.

About the Author

Russell McCullar

Russell McCullar is a senior instructor with the Mississippi State Fire Academy, where he manages NFPA 1006 rescue programs. He serves as a rescue specialist and technical search specialist with FEMA’s Tennessee Task Force 1. McCullar instructs other rescuers around the country, consults with his company, Craft Rescue, and volunteers as an instructor for the National Cave Rescue Commission. He is an EFO graduate and holds a master’s degree in homeland security and a bachelor’s degree in business administration.