A Nightclub, A Fire...And a Generation Vanishes

Natchez, MS, is a charming city, full of the Antebellum pre-Civil War southern mystique and atmosphere found in only the rarest parts of America's historical past. A quick glance of the inner city will stir emotions and make you blink your eyes in disbelief that such beauty still exists. But beneath the beauty lies a dark past leaving an impression that even here life is not safe from the ravages of fire. This is a unique look of 70 years of a fire's history that continues to present itself in vivid memory in this community.

The City of Natchez is the oldest established town on the Mississippi River, founded in 1716 as a fort. In the 1850s, it was a flourishing cotton-growing center, supported by the brisk trading brought via riverboats. Lately, Natchez has become famous for the abundance of its well-preserved Antebellum mansions, many of which are visited by thousands of tourists each year.

The Rhythm Night Club tragedy has not been at the forefront of the city's history. Despite the profound tragedy of the fire and its high death toll, news about the disaster could not compete against the Nazi war machine capturing the headlines with its invasion of key parts of Europe in 1940.

To put things into perspective, with 209 fatalities, this fire and resultant loss of life figures into America's second-highest loss of life in a nightclub-based incident, after the fire at Boston's Cocoanut Grove in Boston, MA, in 1942 that claimed 492 lives.

On April 23, 1940, the Rhythm Night Club was going to come alive with a popular swing band from Chicago, IL, for a one-night performance. It was a Tuesday evening, but that didn't matter to the dance hall attendees, as they had this rare chance to be entertained by the music of Walter Barnes and his Royal Creolians. Barnes was a home state native from Vicksburg, and became successful in the music business. In fact, he and his band were regular performers at Al Capone's Cotton Club in downtown Cicero, IL, for years.

Barnes' music was in high demand throughout much of the live-music industry. He and his band were regular recording artists on the Brunswick label. They enjoyed immense respect from other musicians and bands of that time for their unique application of jazz arrangements for brass-based instruments. In fact, Barnes' music influenced the bands that were to follow his unique style. Duke Ellington's band adopted a similar style of musical selections and arrangements.

The Rhythm Night Club was charging 50 cents apiece for tickets in advance. At the door a ticket cost 65 cents. Records indicate that 577 paid admissions were taken in and 150 passes were also given out. Add to those figures 14 band members and five attendants. The overall total population for that evening was 746 people, packed into a 120-by-38-foot building.

The building had served two other purposes before it became a popular night club for the black community. It was a church and then a garage where automobiles were maintained and repaired for several years.

The construction of the building was interesting, as noted by the Mississippi State Rating Bureau when it conducted an after-fire report for the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). It was constructed by using nothing but two-by-fours with multiple sheets of corrugated metal serving as the exterior walls and roofing material. The interior was lined with one-inch ship-lap material, approximately five feet in height, around the building's walls. The floor was of wood construction, suitable for dancing. Underneath the wooden floor were poured-concrete slabs. Long stud-bolts were sunk into the concrete to help secure the floor. The ceiling was open to the roofline. All of the rafters and joists were exposed. A large number of ceiling fans and electrical lights were hung throughout the structure. Decorations could be easily hung and suspended via the open trusswork.

There were 24 window openings, with 21 covered by shutters that opened to the inside. Because of curiosity seekers and freeloaders wanting a gratis look into the sights and sounds of the club, a management decision was made to nail the shutters closed. Of the remaining three windows, two of the game room windows were iron barred, while a third window was simple glass. There were only two doors at the front of the club, and one was secured with a padlock on the outside. That left only one door being available for all means of egress. And that sole door opened inward.

Decorations to highlight that night's performance called for Spanish moss to be hung throughout the club. The hanging medium was the suspended wire netting tacked along the exposed and open joists. As a precaution against insects, a fresh application of a petroleum-based insecticide was used on the hanging moss. The insecticide Flit was generously applied in the hopes that the club would be bug free for patrons.

The attendees that evening were a cross section of Natchez's black community. On average, their ages ranged from 15 to 25. Almost every black family in Natchez had at least one family member or friend at the Rhythm Night Club that night to listen to Barnes' orchestra. A severe negative impact on Natchez's youthful black generation was in the making.

Fire protection in Natchez was entirely based on a network of 13 volunteer fire companies. All of the fire companies were founded in a deep tradition of community service and honor for well over 100 years. They preferred to be called by name, rather than a number system. Names like Deluge and Phoenix were affixed to the companies' apparatus and engine houses.

The Natchez firefighters took great pride in having the latest in firefighting tools and inventions. In 1940, they had motorized equipment, including the best modern-day apparatus money could buy. Apparatus manufactured by American LaFrance was a mainstay of the department's fleet at the time of the fire.

Although a fully paid fire department would not come for several years, two of the volunteer companies each provided for a full-time firefighter to be available. One of the paid men lived with his family on the third floor of the Phoenix Fire Station, about four blocks from the Rhythm Night Club. Thus, this full-time firefighter operated Phoenix Engine No. 7, being first due at this fire.

It is commonly held that the fire began around 11 P.M. The exact cause never could be determined, as too many factors led investigators into a confused set of circumstances. Even though most agreed that the fire began close to the upfront hamburger stand, it was never pinpointed as the exact cause. What is agreed upon is the rapid spread of flames through the hanging Spanish moss, boosted by the application of the flammable insecticide. The fire quickly took in the large open area of the dance hall with flames everywhere.

The visual horror of a severe fire burning overhead, coupled with oxygen-stealing smoke conditions, put the club's patrons in a state of pure panic. Anyone trapped inside the Rhythm Night Club now had one thought — to escape and survive!

At approximately 11:15 P.M., the fire department received the first telephone call that a fire was burning at the Rhythm Night Club on Saint Catherine Street. An immediate dispatch of the three closest fire companies was rung out to their volunteer members. Paid firefighters Richard Walcott and William Druetter quickly started up their apparatus and began mentally noting which hydrants were close by. They gunned their engines while rapidly shifting gears and simultaneously drove out of the two stations toward the blaze.

Walcott used very little siren enroute to the fire, as the streets were void of traffic at that hour. What he did hear in the absence of his siren was horrific human screaming in the night air. It was becoming louder and louder as he approached the neighborhood of the night club behind the wheel of his powerful engine.

Walcott made the trip in less than a minute, and caught a plug about a block west of the club. He was assisted by a quickly arriving volunteer, and together they laid in with a 2½-inch supply line. He was soon joined on the fireground by Druetter, who was driving his rig with several volunteers on the tailboard. With a working cadre of firefighters immediately present, attention was directed toward getting two streams into the club to knock down the blaze.

One hose stream was taken immediately to the front entrance and trained into the upper ceiling of the lobby. A small open window at the rear of the club was found by one firefighter. This point of access was a direct result of several small-frame patrons who escaped via that opening. A second line was hand-jacked to that location and directed into the open area of the dance hall where the volunteers could see some flame as it burned overhead.

Druetter, who later became chief of department, was at the front of the structure during the firefight. The well-placed hose stream at the front entrance knocked down the fire in about 10 minutes or less, he estimated. Druetter, in his recall of the event several years later, remarked that "the fire was a seething mass of flames, making it impossible for anyone to enter or exit the front of the building." No one came out of the building on their own while the volunteers worked their hoseline.

More volunteers started arriving and were directed by their officers to assist the injured patrons who were outside the building in various stages of distress. Several firefighters, none with smoke masks, tried to make their way into the still-burning club to pull anyone they could see to safety. One came crawling back out and told his teammates that he could not pull anyone out, as he felt that he had run into a huge pile of bodies. His report was soon to be found correct. When the flames died and the smoke cleared, a gruesome scene unfolded.

The overall firefighting and extinguishment went quickly. Whenever a direct stream of water hit the burning moss and wooden timbers of the structure, the fire blackened down. Since the structure was composed of a steel skin, the heated metallic panels immediately contributed to a large production of steam, as the hoselines sprayed upon their surface. All of this aided the prompt delivery of complete suppression against the growing fire. What could not be avoided was collateral damage to the victims still alive inside. After the fire's extinguishment, a number of bodies were discovered to be scalded by the resulting action of the steam clouds and residue of the hot interior atmosphere.

Ambulances arrived at the scene and scores of the injured were rapidly transported to the city's hospitals. Word of the disaster quickly spread across Natchez. The entire medical community responded within minutes and went to the night club or hospitals to help the injured. Despite segregation, the white medical community knew of no boundaries that separated them from these victims. All of the medical profession understood in advance the weeks and months that were to follow in treating and caring for the members of the black community victimized by the fire.

Throughout the night, the firemen, several medical authorities and many civilian helpers worked tirelessly to find any signs of life inside the night club. As floodlights were brought in from the fire engines to light the interior, the scene that greeted emergency workers was too much to bear at times. Bodies were piled on top of each other, many collapsed under the shuttered windows, and all were frozen in time as various stages of human survival could display. One young woman tried to hide in the refrigerator, hoping that neither flame nor smoke would be her doom, but her luck ran out.

Families and friends, co-workers and people from all walks of life came to the Rhythm Night Club throughout the next day. They came to see if there was any hope of finding their missing members alive. Questions continued to be asked — were they taken to a hospital or did they go to stay with friends? Unfortunately, many questions went unanswered. Although most of the dead died from a combination of smoke inhalation and oxygen-deficient atmospheres, there were also a number of bodies severely burnt and could not be identified. They were to share a mass grave.

The popular bandleader, Walter Barnes, did what he could until the end came for him and most of his musicians. He continued to have the band play their music while he spoke calmly over the microphone, hoping to get the crowd into some style of orderly manner for exit purposes. Unfortunately, the power of the fire overtook his courageous efforts. What he and his band members did is respectfully remembered and has become part of their legend. When his funeral took place in Chicago, an estimated 15,000 mourners attended. A mute reminder of the musicians' loss was parked on the adjacent street. Barnes' decorated tour bus sat in a cold, silent and resolute testament that his last gig had been performed.

The horror of this event was not limited to the premises of the night club. The stench of burned bodies hung over Natchez for several months. Citizens woke up and went to sleep with this unforgiving smell. This odor could not be washed out of one's clothing and hair, nor could anyone close their windows to erase the tragedy. With every inhalation this became an immortal haunting element of the fire's tragedy.

The investigation of the fire proved a repeat of findings that fire officials were all too familiar with. Overcapacity with an improper number of exits headed the list. What openings did exist were not designed to open to the outside. Flammable decorations, in particular the Spanish moss, hung everywhere. No first-aid firefighting equipment was available.

What grew out of this affected fire protection and prevention efforts on a large scale throughout Natchez. The posted Building Occupant Capacity sign was to be a permanent fixture in places of public assembly. The development of "panic bar" hardware was perfected. And the impetus for a fully paid fire department for Natchez was started. The city was to create a career force with a full-time chief and fire inspector. They were to be jointly responsible for seeing that the city adopt and enforce solid fire prevention codes and ordinances.

The story of the Rhythm Night Club fire's aftermath could fill a book. Yet no definitive history has come forth to capture the loss. The lives of an entire generation of youth vanished that evening. Their memories continue to sadly remain omnipresent within the City of Natchez.

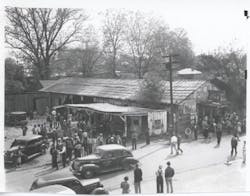

The location is easy to find today. One can simply head downtown to find the "Triangle" and there is the site, at 5 Saint Catherine St. The original building was razed many years ago. The site's present owner, Monroe Sago, ran an auto-detailing shop that occupied a small part of the concrete slab until the weekend of the 70th anniversary of the tragedy. He and his family have now turned his work building into a modest, but befitting museum. Sago plans to expand his initial groundwork and is looking toward a hopeful future that others will assist him in his efforts. He strongly desires to have the history of the Rhythm Night Club fire displayed for future generations at the original location.

On April 24, 2010, a community-wide memorial service and museum dedication took place on the original site. Two of the three living survivors of the fire attended. The program involved speakers, music, poetry and a prayer service. A fellowship of families, friends and community supporters concluded the afternoon's events.

A historical marker is on the adjacent sidewalk. The original metal pole and hollowed-out electrical sign still stand as stark reminders of the tragedy. The Natchez community keeps the memory alive by conducting an annual memorial service. A bronze memorial plaque was placed on the bluff overlooking the Mississippi River on the west side of town shortly after the fire.

This year's 70th anniversary was recognized by many of the participants and family members. Their feelings and discussions noted that improved fire safety measures, not only for the Natchez community but throughout the country, have come out of this tragedy. And yet ever so quietly, family and friends will still gather, remember their loss and continue to ask, "Why?"

The author wishes to thank the following individuals who provided research guidance for this article: Lieutenant Jamal McCullen, Training Officer Darrel Smith, Chief Oliver Stewart, Director Mimi W. Miller, Director Darrell S. White, Monroe Sago and Richard Walcott.

MICHAEL L. KUK, Ph.D., CFO, is the fire chief at Fort Polk, LA. He has over 40 years of fire service experience and has been a published author since 1974. A Vietnam veteran U.S. Army firefighter, he is the chair of the Federal Firefighters Memorial Committee and Master Musician for DoD ceremonial events. He was recently inducted into the Army Fire Chiefs Hall of Fame and in 2006 was inducted into the Iowa 50–60s Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame with his band, the Union Jacks, of that era. He is an avid fire memorabilia historian and collector, in particular with items pertaining to Saint Florian. He wrote about the "Cherry Mine Fire Disaster" in the November 2009 issue.